Last December, we got on a plane in Guayaquil, and by the end of the day were here, in Cartagena, Colombia. Its narrow streets and balconies, and its colorful, crumbling walls greeted us as we sped by taxi inside the old stone walls surrounding the historic downtown.

Last December, we got on a plane in Guayaquil, and by the end of the day were here, in Cartagena, Colombia. Its narrow streets and balconies, and its colorful, crumbling walls greeted us as we sped by taxi inside the old stone walls surrounding the historic downtown.

Actually, we got there at night, and the narrow streets and crumbling walls were a little disconcerting as we formed our first impressions. We scanned the dark and empty street that was the backdrop to the front door of our hotel, it little more than a painted metal gate opening into a set of white tile stairs, flickering under the fluorescent bulbs above, leading up and around a corner inside the building.

I had made a reservation at this hotel while we were still in Cuenca. I followed the standard rule that you don’t go with the cheapest nor the most expensive place when it’s sight unseen. But I did go lower than I originally intended to. When I called the first place on my list and inquired about the price per night, I heard “seijenta mil pesoj” from the man on the line, breathing through his s sounds. Wait a minute. 60,000 pesos? I admit I hadn’t taken the time to check the conversion rate before the call, but that sounded like a lot!

So I told him no, thanks. Then I called the next cheapest place. It was 50,000 pesos. I still didn’t know what that meant in dollars, but these were certainly not the hotels at the top of the list in my guidebook as it was, and I didn’t want to keep going lower. So I agreed. And now, here we were. And, 50,000 pesos turned out to be about $25.

As we wound our way up into the building, we saw that the white tile of the stairs matched the white tile floors and white tile walls, and the smell of floor cleaner and mothballs was slowly invading our noses. The man at the reception desk checked my name and showed us to our room, which had an air conditioner, no windows, and a broken doorknob. We examined the doorknob skeptically, and asked for a different room. The alternative was upstairs, still lacking a window and also lacking A/C. But the lock looked good and it wasn’t that hot, so that was where we stayed.

The next day we began our exploration of the city. It was a blazing, dry, sunny heat that embraced us as we left the building, disoriented in time by the lack of windows. Part of our agenda for the day was to scope out some better lodging, and that we did. One with a much nicer traveler’s feel. One with wood floors, an airy common room with big couches and internet access. It also had a wide common balcony that overlooked the street, the public square on the corner, and the orange church you see above.

Although the picture above was not taken from the balcony of our new accomodations, but from Cartagena’s famous murallas.

Cartagena, historically, was a strategic port for the Spanish colonies in South America. As such, it was a ripe target for foreign attackers, like Francis Drake in the late 1500’s. After being sacked numerous times by the English and French, the Spanish crown began an extensive investment in Cartagena’s defense, including these walls, which encircle all of the historical heart of the city. The project took two centuries to complete, and while they were effective in protecting the city from subsequent attacks, the walls were not fully built until 1796. Considering Cartagena won its independence from Spain in 1821, you might say the Spanish never got a full return on their ambitious investment.

Today, the walls have become many things. Museums, restaurants and shops line them above and below. Parks have sprung around them, both inside and out. And tourists like ourselves stroll along them from end to end, pursued shamelessly by vendors and beggars.

And within the walls lies the maze of streets, plazas and alleys of old Cartagena. To further confuse the visiting wanderer, literally every block of every street goes by a different name. We indulged in exploring these streets without a map, turning left or right or not at all, as we pleased.

At the time, I was reading Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, one of the most exemplary tales of his life, going from café to café around Paris, in constant search of that delicate balance between seclusion and stimulation that got him into the writing mode. Guided perhaps by this fine example, we made a point to try and have every meal in a new place, and often wandered for over an hour before settling on a place we’d passed a half dozen times. All in the name of good dining and exploration.

One popular dining spot was here, the outdoor plaza in front of Cartagena’s Santo Domingo church. There were six competing restaurants in this plaza, by my count, and all of them featured waitresses eager to greet you with a smile and put a menu in your hands. This aggressive strategy wasn’t always well received by us, but I’ve got to admit how effective it was. This plaza was almost always full, regardless of the time of day or night.

In the end, we ate there a couple of times, at two different restaurants, despite the fact that at either one of them a plate of ordinary pasta ran about $20. Maybe that sounds like a lot and maybe it doesn’t, but after a couple of years in Cuenca where lunch regularly runs me $2-4, it felt steep to me, especially considering the food wasn’t that great. But, it was a great place to watch the locals and tourists and enjoy some superb sunshine and sea breeze.

While we could have spent all our days leisurely strolling the streets of Cartagena, stopping at our whim for coffee, juice, lunch, or simply a rest in a shaded patio. And many days were spent doing just that. But Cartagena lies on the edge of the warm turquoise waters of the Caribbean Sea, and so many days were also spent in search of the perfect beach.

Our first attempt was the nearby Bocagrande.

While Cartagena faces the sea, it faces it with a rocky coast and the back of its formidable walls. Ships seeking to enter its ports must therefore do so through one of two mouths of a bay leading to its gates.

The innermost waters of the Bay of Cartagena is girded by the peninsula of Bocagrande, while the mouth of Bocagrande itself has been blocked by an underwater wall which confounds the passage of large vessels.

As a result, pirate ships were forced to approach the city through the smaller mouth much further to the south, the aptly named Bocachica.

Bocagrande today is Cartagena’s answer to Miami Beach. The narrow, sandy peninsula has given rise to tall hotels and condos, a stark contrast to its colonial old town, and only 15 minutes by foot from its limestone walls. We did find beaches there, but I’ll say without hesitation that the greatest beaches are ruined by ambitious developers the world around, and we were quickly turned off by the tall buildings and swarms of people crowding them from end to end. So it was that we spent little time there before we made our way back downtown.

Another journey led us to the promising Playa Blanca. This beach, lying two hours from Cartagena by boat, is located on the Isla de Barú, and all descriptions painted a picture of a peaceful and natural beach:

And indeed, upon our approach we caught this glimpse of an archetypal Caribbean beach. Palm trees, straw huts, nice sand and impeccably warm sea, with a lush tropical forest nestling it from behind. The trouble was that we made our approach in a big double decker tour boat, flanked by a couple more just like it.

We brought the party with us, and soon that nice beach became overrun by throngs of tourists, and the locals who prey upon them. A relaxing moment in the sun and sand was quickly interrupted by people plying coconut water, massages, suntan lotion, seafood, or candy. A soak in the soothing waters was frustrated by the lack of regulation of watercrafts, which pulled up to the beach wherever they wanted, while whatever swimmers in the way were expected to shove off.

I suppose this beach would be a very pleasant place when visited independently of an organized tour. Unfortunately for us, we were unaware of the scope of the tour we had embarked upon, and our experience in the beautiful Playa Blanca was tainted by the sunbathing masses.

Fortunately, our third attempt to find a pleasant, beautiful and peaceful beach was the charm.

This is the beach at Bocachica. Lying at the southern tip of Isla de Tierrabomba, its shores form the top of the smaller mouth of the Bay of Cartagena.

The Spanish constructed the outermost fortifications of their colony here, at both sides of this sea passage.

And so, before we got a look at this uncrowded and authentic Colombian playa, we first saw the relics of Spanish ambition:

El fuerte de San Fernando. This stone fort once bristled with cannons, and its walls are lined with slits that widened into the interior, allowing soldiers to fire out of them while preventing enemy fire from entering so easily.

On the other side of Bocachica lies the Batería de San José, another, smaller fort. Between these two battlements was once stretched a heavy metal chain, one more line of defense against attack.

Today, safe from piracy and what have you, Bocachica has been dredged through, creating a deep underwater furrow that modern shipping vessels use to transport their cargo. This has helped Cartagena to maintain its importance as a major South American port of the modern age. Indeed, on our way over to the beach we saw this big ship on its way into the bay:

It was surprising to see a massive boat like this one able to pass through such a narrow corridor in the sea.

Fortunately for our beachgoing, however, this was one of only a few big ships to pass by us that day. Enough to make the scenery more interesting, but not so many to have marred the beauty of our surroundings.

And so, around the corner from this big fort was the village and beach of Bocachica. The island of Tierrabomba, to the north of which has remained mostly wooded and wild, has to its south a small and fascinating community.

Tourism has passed this place by, for the most part, with the majority of travelers heading directly through the mouth of the bay on their way back and forth from Cartagena to various islands and beaches further to the south. And so this village, while eager to receive tourists when they come, is otherwise by and for the villagers themselves.

That left the beach to us, and some kids out for their day in the sun. We took our time enjoying the peace and the warm waters that the beach offered, and then found a hut in the sand where a woman sold lunches. Fried fish, veggies, and coconut rice, with lime for seasoning, and a cold beer. Nice.

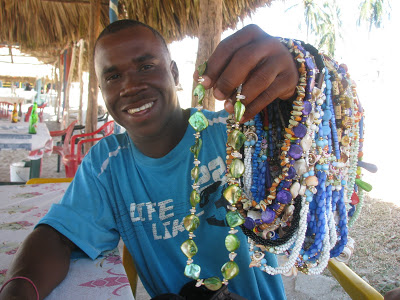

Plus, this fellow, who frankly, and smiling, told us that he wasn’t going away until we bought a necklace from him.

We put him to the test, and went about our lunch without paying him much mind. He sat there, unobtrusive except for when he had something interesting to contribute to our conversation. But sat there he did, for about half an hour. We had finished our lunch, and the beer, and were contemplating our next move. But, since Nancy had souvenirs to get for her sisters and family, and we had here before us a hardworking but friendly salesman, we caved and gave him some business before we left.

Our walk back to the docks led us through the village, and in the late afternoon breeze, people were gathering together for some shade and refreshments outside their homes. On the way past a house where a few dozen people were hanging around, a man came up to us and handed us a couple of beer bottles, and motioned for us to have a seat in the shade. And so we did. The man went into the house and left us be to enjoy the afternoon and the beverages he had offered us.

The people around smiled at us and gave us welcome, but also left us in peace, to be part of their scene without any overt attention. Some cumbia was playing, of the sort that belies its Caribbean and African roots the best.

The whole house was full of people, and so was the yard, sitting, standing, some dancing, talking, singing. After we hung around for awhile and finished our drinks, we got up, and I suggested to a man sitting near us that I pay someone for the beer. A shake of the head and a motion of the hand made it clear that no payment was necessary, and the smile we shared afterwords said the rest.

Satisfied at last with a day at the beach, we turned our tourists’ eyes towards another piece of Cartagena’s long history of self-defense, the Castillo de San Felipe de Barajas.

Lying across a small lagoon from Cartagena’s old town, this massive fort began as a more modest fortification sitting atop this 40 meter high hill. In the mid 18th century, however, it was extensively expanded until it appeared much as it does today, completely covering over the hill that it was built upon. Loaded with cannons and designed with a myriad of techniques with strategic defense as their aim, this fort was never taken, despite several attempts to do so.

The walls were built at steep angles, sheer enough to prevent enemies from easily scaling them, but at enough of an angle to allow soldiers from above to spot oncoming attackers without looking out far from the edge.

A maze of tunnels riddle the fort’s interior, carved out in such a way that sound reverberates throughout them all, allowing even the slightest sound to be carried to the ears of the defense. To enter the tunnels, one must make a steep descent into total darkness, after which the tunnels generally adopt a level slope. Defenders lying in wait at these points could easily see and shoot anyone entering, long before the tunnel’s entrance would carry them low enough to see inside, even if their eyes could adjust to the darkness that quickly.

Further taking into account the limitations of human sight in low light, the tunnels are lined with small alcoves to the left and right, where soldiers also once waited in ambush. While the tunnels admitted enough light for a man whose eyes were well adjusted to the darkness, anyone fresh into the tunnels would have no awareness of their presence, until they were blindsided by the attack.

All of these and other methods of defense were explained – and sometimes demonstrated – to us in detail by our helpful guide, whose English was at least as easy for me to understand as his Spanish. He also explained Cartagena’s many rings of protection. The outermost ring, he told us, was the Spanish Armada. At all times, ships were strategically deployed in and around the Bay of Cartagena, ready to defend and call the alert. Inside of this were aforementioned defenses around the two mouths of the Bay of Cartagena. Further in were the forts such as this one, scattered throughout the islands and peninsulas that surround the city. Then came the city’s walls themselves. Lastly came Cartagena’s own human resources, where espionage and information were as valuable and convoluted as they must still be today.

Which led me to ask, why is protection so important? Why did the Spanish endeavor to spend so much of the wealth that they funneled out of the Americas in order to ensure its safe passage back to their ports in Europe? I suppose every wall has the same story. In our often mindless pursuit of wealth and prosperity, there comes a point where the need creeps in, to protect everything we’ve worked so hard to scrounge together. And so while Cartagena’s extensive fortifications represent an extreme example, may we all think for a moment, every time we lock a door or set an alarm, about the other side of human ambition, our constant clambering for all things deemed valuable, or beautiful.

On our last night in Cartagena, we sat in the Plaza de Bolívar. Here is the statue commemorating El Libertador, who saw, and briefly realized, the dream of a united Gran Colombia, hundreds of miles to the south and a few short decades after the first great experiment in American independence, by the British colonies. Before it was the Plaza de Bolívar, it was the Plaza de la Inquisición, where the Spanish once publicly delivered punishment to those found guilty of blasphemy. In 5 public autos de fe held in this small square, an estimated 800 received that ultimate consequence, as public examples.

A visitor to this park today, listening to the band playing la pollera colorada, doesn’t need to know any of that. Instead, one sits peacefully, drinking coffee, or eating yellow pineapple, watching the big fountain overflowing. All the history, the greed, the pirates, the people who died in centuries of battles posturing for their own tenuous hold on a place, all that has led to this moment. Sitting idly, in peace. That’s what we want when we build our walls. To create a respite from the wind, from the sea, from change, from the masses and their collective ambitions. And like the music that rises up into the air, we enjoy it, we breathe it in, while it’s there. All while we know that it all still will change, and drift away.

Brian Horstman is a teacher of English as well as a traveler, writer, photographer and cyclist. His interest in traveling around Latin America began while he was living in New Mexico, where he began to experience the Latino culture that lives on there. From there he spent time in Oaxaca, Mexico and has since been living in Cuenca, Ecuador and will be living in Chile starting in 2011. Cal’s Travels chronicles some of his more memorable experiences from Mexico and Ecuador, as well as some side trips to other parts.