I, my friends, am a brewer. I like beer, and I like to make beer. I wouldn’t say I’m a pro at it, but I’ve been doing it off and on for many years. I started brewing in college, and anywhere I’ve lived for more than a few months, the urge to gather the materials and ingredients necessary to brew up a batch begins to occupy a prominent place in my thoughts. Not long thereafter, the kitchen fills with a sight like the one you see above. An over-sized pot on the stove, filled as close to the brim as I can manage with sweet liquid goodness and topped off with a foamy head evocative of the first sudsy glass I’ll be pouring in a few weeks’ time. There are surely plenty of websites out there that will do a better job than I will of explaining the brewing process. And there are excellent manuals on the subject, like the one I use: a beer-stained volume entitled The Complete Joy of Home Brewing. Rather than walk through the process then, I’ll instead be sharing some of my own personal experiences with brewing, along with some photos that will hopefully get your mouth watering and mind turning over the idea of trying to brew it yourself someday, if you don’t already.

I, my friends, am a brewer. I like beer, and I like to make beer. I wouldn’t say I’m a pro at it, but I’ve been doing it off and on for many years. I started brewing in college, and anywhere I’ve lived for more than a few months, the urge to gather the materials and ingredients necessary to brew up a batch begins to occupy a prominent place in my thoughts. Not long thereafter, the kitchen fills with a sight like the one you see above. An over-sized pot on the stove, filled as close to the brim as I can manage with sweet liquid goodness and topped off with a foamy head evocative of the first sudsy glass I’ll be pouring in a few weeks’ time. There are surely plenty of websites out there that will do a better job than I will of explaining the brewing process. And there are excellent manuals on the subject, like the one I use: a beer-stained volume entitled The Complete Joy of Home Brewing. Rather than walk through the process then, I’ll instead be sharing some of my own personal experiences with brewing, along with some photos that will hopefully get your mouth watering and mind turning over the idea of trying to brew it yourself someday, if you don’t already. All homebrewers in the US, and therefore all microbrewers there, as well as everyone else who enjoys drinking something beyond commercial pilseners, all owe the fine hobby to an enlightened Act of the 95th Congress which was later signed by Jimmy Carter. Before then, homebrewing was illegal in the United States, ever since the days of Prohibition. During all those years, there weren’t many people in North America who were drinking anything more innovative than beers like Rolling Rock, Heineken or Michelob, if they got that far beyond your standard commercial beers.

All homebrewers in the US, and therefore all microbrewers there, as well as everyone else who enjoys drinking something beyond commercial pilseners, all owe the fine hobby to an enlightened Act of the 95th Congress which was later signed by Jimmy Carter. Before then, homebrewing was illegal in the United States, ever since the days of Prohibition. During all those years, there weren’t many people in North America who were drinking anything more innovative than beers like Rolling Rock, Heineken or Michelob, if they got that far beyond your standard commercial beers. Every batch of beer I’ve made has been an ale, and usually with an assortment of equipment and ingredients thrown together from any source I had access to. The first batches I made were crafted from materials bought at the local home brewers’ supply store. When I was brewing North American ales in Ecuador, I did my best to time the batches of beer I made to coincide with visits to the US, when I would bring ingredients down with me, like these pungent hop pellets.

Every batch of beer I’ve made has been an ale, and usually with an assortment of equipment and ingredients thrown together from any source I had access to. The first batches I made were crafted from materials bought at the local home brewers’ supply store. When I was brewing North American ales in Ecuador, I did my best to time the batches of beer I made to coincide with visits to the US, when I would bring ingredients down with me, like these pungent hop pellets.

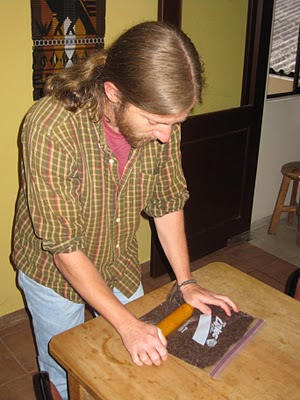

The rest of the equipment I needed was easy to find, and so it was time for brewing, at last. For an amateur brewer like myself, that means a process that includes cracking grains, like the ones you see in the plastic bag. Ziploc and a rolling pin is the way I crack them, short a hand-cranked grain mill as I am.

For the batch of porter I happened to be making, I was using some of the darkest roasted barley I could find, which gives the beer a nice brown/black color and an even nicer malted flavor. Put that together with your malted grains, hot water, and when the time is right, your favorite assortment of hops as pictured above. Then you end up with an aromatic stew that fills the house with a pleasantly sweet smell for the next several hours. And of course, eventually you get beer, which is ultimately the point of all of this.

Once you’re satisfied that your beer is well cooked, you fill up one of those big bottles with it. If you’re as lucky as I am, you even have an assistant who smiles and holds the funnel.

Once you’ve brewed your beer, you mostly have to wait. You’ve stacked up a sugary solution with the natural preservative power of hops, and then loaded it with activated yeast under more or less controlled temperatures. Often overnight, all those natural forces you’ve set up begin to have their way with one another, bubbling away in a sure sign that alcohol is being coaxed forth from sugar molecules before your very eyes.

But once all that initial activity is over, the beer will just sit there for quite awhile longer, and unless you look closely it doesn’t look like much is happening at all. But at the bottom of the barrel you’ll see a bunch of thick residue forming, and the idea is to keep your tasty beverage away from it. That’s why many brewers, even low-tech ones like me, opt for a two-stage fermentation in which the liquid is transferred carefully to a fresh vessel and the detritus is left behind.

This all ads up to invoking yet another scientific principle in your own kitchen, that of the siphon. And that’s about all the action you’ll get from your beer for a couple of weeks or so.

Until it’s time to bottle, which means more siphoning, and also the satisfying task of capping your carefully kept empties. Looking at the progression of photos, it would appear that I had nothing better to do between the various steps in the process than let my beard grow. And after this fateful day, when the beer found its final resting place before its eventual consumption, came more waiting. Once in the bottle, the beer is conditioned.

It sits undisturbed, naturally clarifying thanks to the forces of gravity drawing the final remnants of particulate matter to the bottom of the bottle. It also develops carbonation naturally, due to the extra sugar solution I introduced upon bottling. In the presence of this fresh dose of sugar, the last vestiges of active yeast living in the premature beer awaken one last time. It produces carbon dioxide and pressure to preserve the beer for months within the bottle, and also puts bubbles in your beer – again, with time. If you’re impatient, you could drink the beer the moment it’s bottled. Just throw it in the blender before you drink it, and it will be just as bubbly as a well-finished product. But most brewers will agree that a couple more weeks and it will naturally develop the perfect foamy top, all by itself.

And that’s the end of the story. Bottles full of beer are like potential energy, and you get to choose when to unleash it, and with whom. But after all that waiting, you’ve had lots of time to consider what to do with your newly found powers. Choose wisely!

Brian Horstman is a teacher of English as well as a traveler, writer, photographer and cyclist. His interest in traveling around Latin America began while he was living in New Mexico, where he began to experience the Latino culture that lives on there. From there he spent time in Oaxaca, Mexico and has since been living in Cuenca, Ecuador and will be living in Chile starting in 2011. Cal’s Travels chronicles some of his more memorable experiences from Mexico and Ecuador, as well as some side trips to other parts.