I love to go to art fairs, where in a few hours one can visit dozens of galleries, often from around the world. New York is particularly rich in them—the Armory Show, Scope, Volta, Outsider Art, AIPAD (the photography fair), and many others. But I had heard that the Venice Biennale was unique among art fairs, and indeed it was: each gallery—or country in many cases—presented a single artist, mostly in large-scale installations, so that one walked from one head-spinning environment to another—but I get ahead of myself.

I returned to this romantic city after 50 years this past summer. I had hitchhiked there at age 20 in 1967, speaking no Italian, and stayed on the Lido island across the Grand Canale from Piazza San Marco. Now I was back, fluent in Italian and determined to see the Biennale and as many Venice galleries as I could in three days, including the much-touted Damien Hirst show.

On my initial vaporetto cruise into the city from the bus depot at Pizzale Roma, I couldn’t stop photographing the iconic architecture that ended at water’s edge and the ubiquitous gondolas. All of a sudden I saw two hands surge from the canal, grasping the side of a building. Ah, Venice, I thought. Not a city to rest on your laurels, your overly familiar uniqueness. You still have some surprises to spring on your lifelong votaries. And I knew I had made the right decision to visit the Biennale and give more time to this magical place.

Hands on a Palazzo—Seen in Oassing from Vaporetto upon Arrival

The Biennale

I spent the first two of my three days in Venice visiting the Biennale, an immense international exhibition in the old Arsenale and in the Public Gardens, the latter where countries had their own permanent buildings. I still didn’t manage to see all of the Biennale, only about 93% of it, but every inch of it is worth it. The Arsenale, a relic of Venice‘s military past as a world maritime power, couldn’t have been a better site for a monumental art exposition: scores of huge empty chambers, many of them naturally dark, perfect for the most diverse collection of grand-scale installations, including videos.

Powerful original environments alternated with fanciful ones, so that a stroll through their succession became a journey through a series of bizarre imaginative realms. Most were fascinating, and some stood out by their extravagance, for example, the huge panoramic 100 feet long video screen, mounted by New Zealand, that depicted the arrival of British sailors and officers and their peaceable encounter with the local Maori tribesmen. All movement was in slow-motion, and the whole scene gradually moved off to the left.

British Navy arrives in New Zealand and meets the Maori, New Zealand expo at 2017 Biennale

British Navy arrives in New Zealand and meets the Maori, New Zealand expo at 2017 Biennale

In this Biennale exhibition, some stood out with their power to evoke human diversity, such as Ecuador’s extensive collection of roughly carved wooden masks mounted on metal rods in a circular crowd in the middle of a large room. On the walls in red letters marched a long list of languages native to the country.

Ecuador’s Wooden Masks at the Venice Biennale

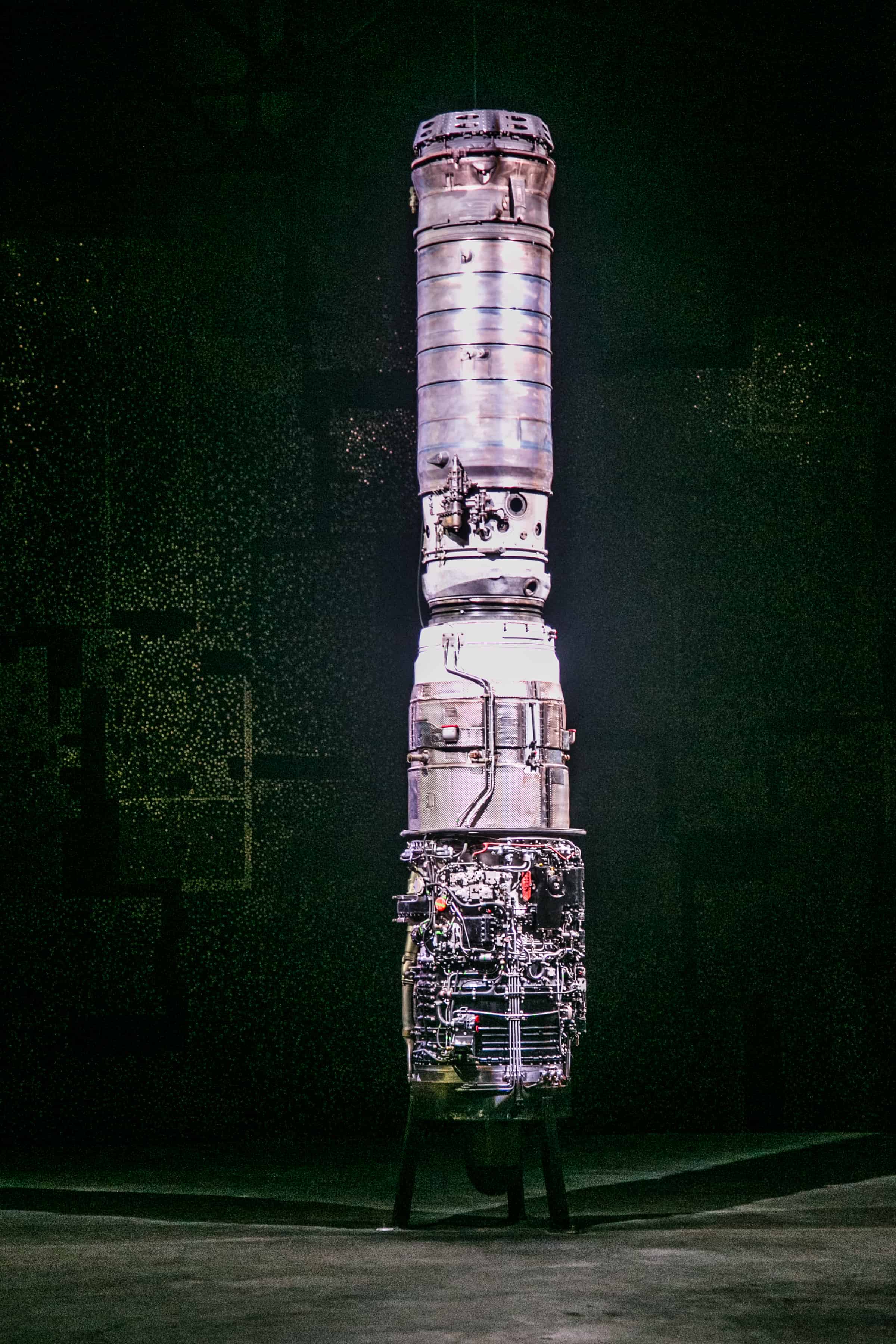

Lebanon ushered a group of viewers into a dark room and slowly brought up a spotlight on an imposing new godhead: a floor-to-ceiling cylindrical robot with its computer workings on the outside.

Computerized Sun Godhead at the Venice Biennale

Israel had a single piece in its dedicated building: a huge soft sculpture made of a cottony fibrous material representing the discharge of a firearm. Its meaning was ambiguous: life there reduced to the violence of an explosion. Was it complaint or criticism?

Israel’s One-Piece Exposition: an Explosion, at the Venice Biennale

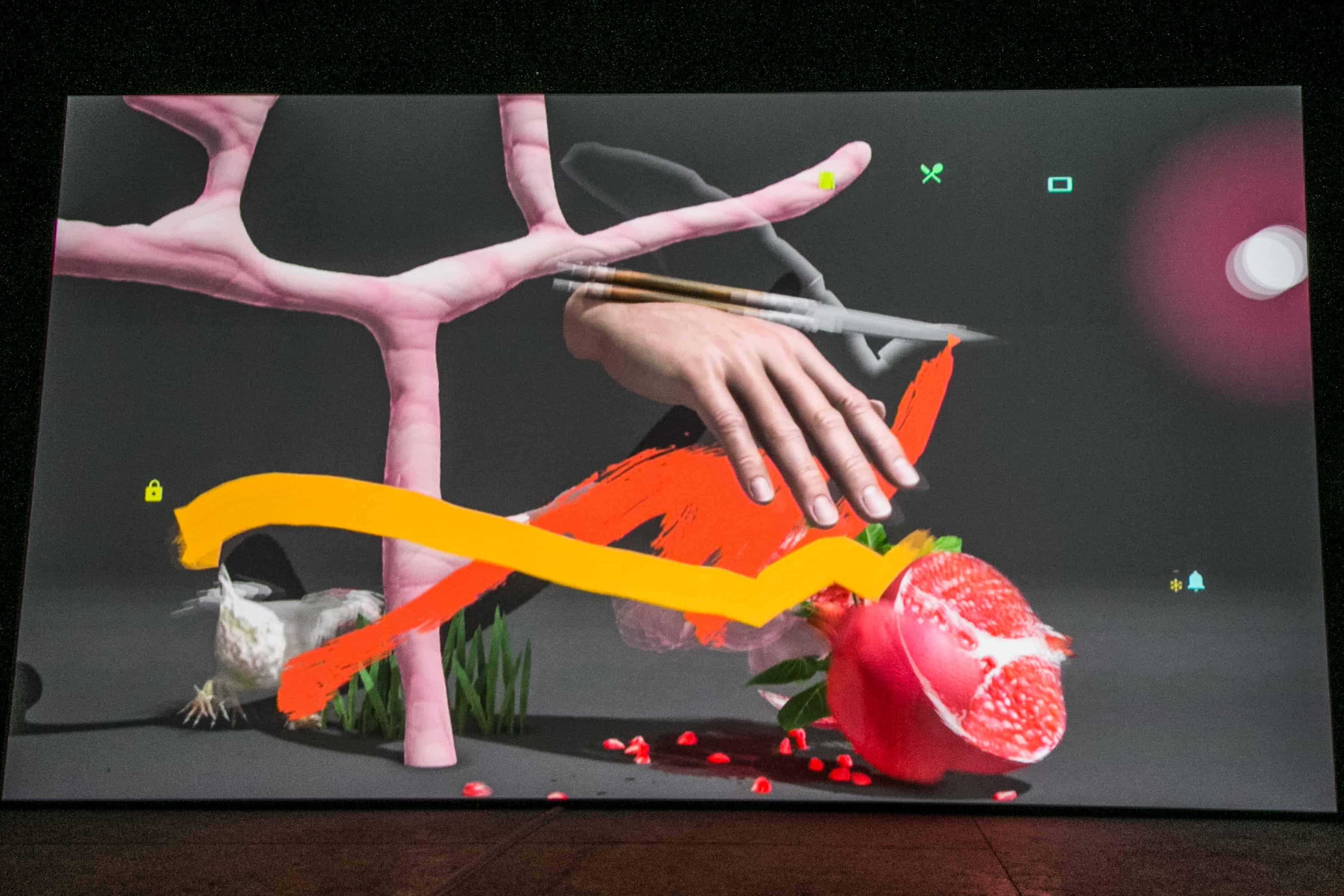

There was a rather capricious computer-generated video at the Biennale in a huge dark room toward the rear of the Arsenale:

Computer-Generated video on huge screen in a rear chamber of the Arsenale at the Venice Biennale

There was a rather sober meditation on death and decay that seemed to exhibit exhumed bodies by three Italian artists:

Il Mondo Magico by Georgio Andreotta Caló, Roberto Cuoghi, and Adelita Husni-Bey at the Venice Biennale

Biennale visitors could enter one of the installations, lie down and meditate:

Una Ist Kayawa: Book of Healing by the Huni Kut People of the Jordão River (Southern Brazil, tributary of the Pirana River) – Biennale

Una Ist Kayawa, external view – Biennale

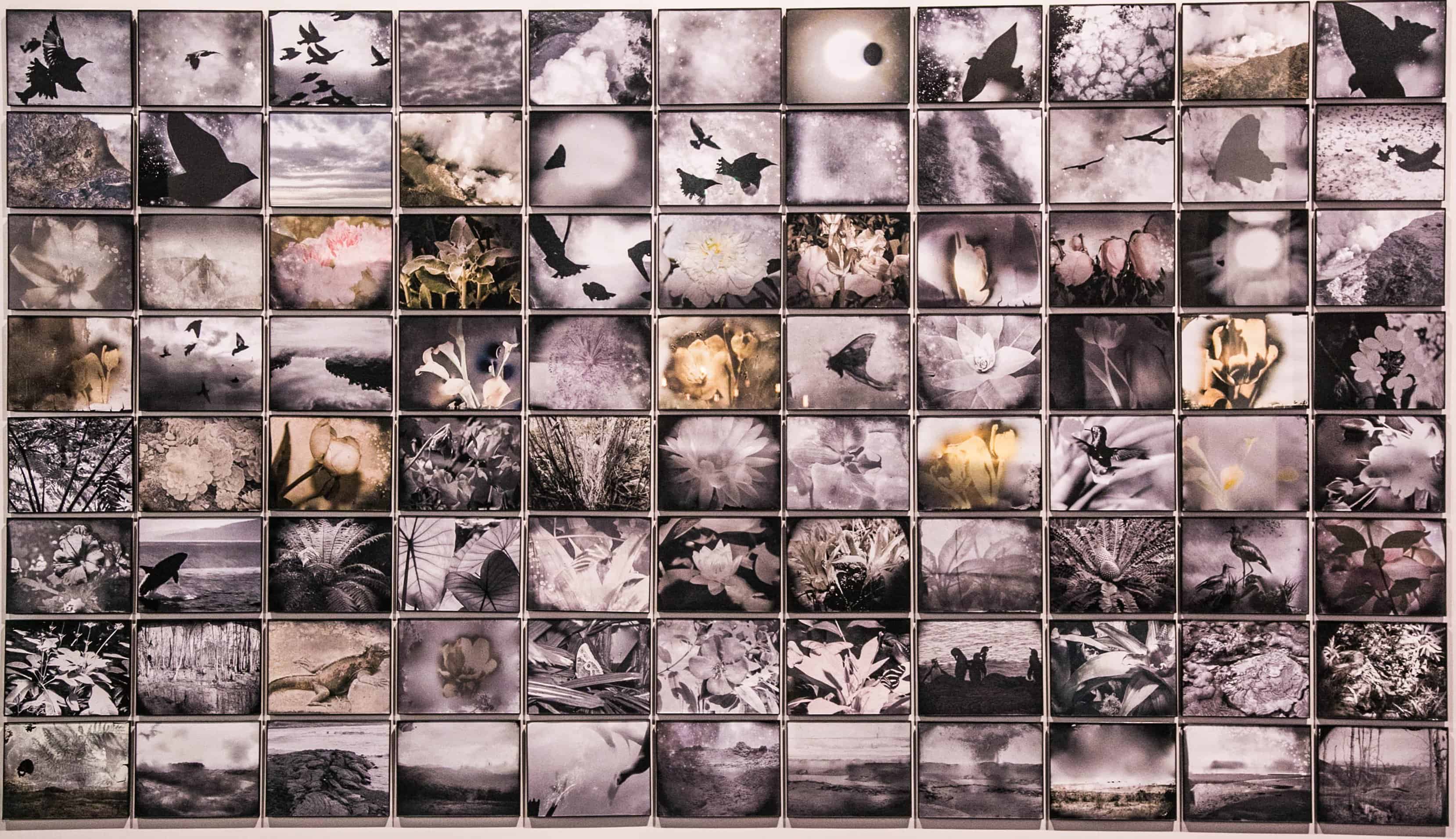

There was even some conventional art-on-the-wall work shown, although this grid collection of photographs made to look as though using an archaic process, mounted flush to glass stood out for me as a mental evocation of a wetland with lotus, lilies, ferns, birds, and luna moths:

Flight of Time, by Michelle Stuart (American, b. 1933) – Biennale

And these fanciful hanging sculptures at the Biennale that might at first glance evoke aggressive flowers, but that are actually assemblages drawing from a variety of cultures:

“When signs of origin fade, fall out, if washed away, trickle into separations, precipitate when boiled or filtered to reveal all doubleness as wickedness, vanishing act that migration, mixataion like mothers show hid paternity who could name move me slowly reveal me only when my maker stands straight.” by Rina Banerjee (b. India, 1963, made of turtle replica in resin, vintage shell lampshades, steel armature, Polynesian wood mask, Pyrex filtration lab glassware, perfume oil, rooster feathers, thread, linen, silk, amber vials, cowry shells, seed beads, pearls, plastic net trim, porcupine, sequin & silk thread.)

Amid many other wonders at the Biennale, this one struck me as playing creatively with questions of what is real and what is not: a rough-walled hall of mirrors and empty frames, confusing real space with virtual, and strewn with isolated standing rocks. It was the first thing I saw on day two of my visit to the Biennale and served to disorient me happily out of middle-level reality…

The author/photographer is the figure on the extreme right.

You see Venetian carnival masks on all the mobile souvenir stands in Venice. They hit you as soon as you step off the airport bus, and those are not that expensive. I resolved to buy one or two on my way out of town.

But on my way back to my lodgings that first evening I passed a mask shop that was so over-the-top, I just had to go inside. Then I was even more overwhelmed with the relentless mask profusion of the Ca‘ del sol (“Ca‘” is Venetian dialect for casa, house).

Every type of mask in the Venetian carnival tradition was represented in what seemed to be every possible iteration. Some were new to me, such as the painted scene masks, and I was particularly captivated by the ram horn masks—so much so that I shelled out 70€ to bring one home. They seemed to play upon an image of lusty male energy. I’ve circled the one I bought in the second photograph, below.

Ca’ de Sol, mask emporium

Ca’ del Sol, mask emporium, with ram horn masks below. I bought the one circled in red.

Ca’ del Sol, mask emporium. I had never seen the painted portrait nor the painted scene masks.

I was invited into the mask workshop across the street from the showroom.

The ostrich feather table, Ca’ del Sol mask emporium workshop

Hamid, owner, artisan genius behind the mask world of Ca’ del Sol

The Museo Carrer: Archeology & Venice History

On my third day in Venice, a Monday, the Biennale was closed. I felt I had the city to myself now and was free to explore its other art wonders. I decided I would finally return to the Basilica San Marco, one of the most beautiful in the world, arguably with more interesting and older art than that of San Pietro in Rome.

This was, after all, the principal cathedral of a late medieval and early Renaissance international maritime empire, heavily influenced by the Byzantines, their imperial neighbor to the East, with whom they maintained a prosperous mercantile relationship. I had seen the cathedral in 1967 and distinctly remembered the gisant statues of the four-foot-long buried cardinals above their tombs in niches. They had to be there still.

Crowds at the entrance to the San Marco Basilica

I arrived before it opened at 9:30 and stood in the shorter line to go in. But once at the door I was turned away: that was the line for those who had made on-line reservations. Moreover, no photography was allowed inside! So, after fifty years, you couldn’t just waltz into San Marco. And no photography! So I turned on my heels and proceeded to the archeological museum, which was part of the Museo Correr, on the far side of the immense Piazza San Marco. It didn’t open until 10, so once again I was early.

When I finally made it to the ticket desk, the upbeat, singing man at the ticket counter told me I’d have to buy a composite ticket for that museum, the Ducal Palace and the Campanile for 20 euros, and no, they didn’t extend privileges to journalists or travel writers.

The best he could do, though, was issue me a free ticket to the special exhibit of Iranian photographer Shirin Neshat (b. 1957), whose 55 impressive large-scale portraits of the diverse citizens of Azerbaijan hung somewhere two floors up. I took it and skipped happily up the marble staircase, where the blond woman official took a quick look at my free ticket and let me through.

No one was stopping me from seeing the whole museum! I felt a little like Max Ernst, when he was trying to get out of France at the beginning of the War, and subject to French internment as a hostile alien. The border official to whom he showed his rolled-up canvases recognized him as a talented artist, and told him with a wink that he should NOT get on THAT TRAIN OVER THERE, which was going to neutral Spain, which he promptly did, thus probably saving his life.

The part of the museum before the archeological part contained objects, documents, paintings, an extensive library, and impressively sized globes from the time of Venice’s heyday as a world maritime power, fighting frequent wars at sea, and mounting triumphant festivals. This was official, political Venice during its time of greatness, from the 13th Century through the 18th.

This encompassed the time of Marco Polo in the late 13th and early 14th Centuries as well as the major explorations around the globe by Spain, Portugal, England and France starting in the late 15th Century by the great Genovese navigator, who gave us a national holiday, and the following two centuries when these explorations really gained momentum and sparked the imaginations of European populations.

No Italian city-state was rich enough to sponsor any of these expeditions, but the Venetians followed them closely. Their globes featured quite accurate representations of South America and the Caribbean, but were very sketchy about North America, mostly the domain of Protestant England, although they seemed to get the Great Lakes right.

Globe and library in the Museo Carrer, a museum on Piazza San Marco that combines the history of Venice with an archeological musuem.

There was also a room with an extensive collection of medallions honoring the succession of Venetian Doges or Dukes. My father had told that Venice had Doges as their heads of state, but they never represented particular individuals in my mind until I saw this collection. Every one had a name, of course, and a duration of his administration.

Medallion commemorating Alvise III Mocenigo, Doge (Duke) of Venice in the early 18th Century

As a world power, Venice flourished between the 11th and the 18th Centuries, then fell to Napoleon on 1797. Its apogee, however, was during the 15th and 16th Centuries, when the city (pop. 180,000) was second in size only to Paris, and its possessions extended down the Istrian coast (present-day Croatia) and included many Aegean Islands, including Crete and for a time even Cyprus (total population of the Venetian empire: 2.1 million).

Much of its strength came from the fact that it was a “republic,” which meant that its Doges were elected by a Great Council composed of wealthy merchants and civic leaders, thus ensuring that its government served their collective interests and not just that of a ruling family, as in other Italian city-states.

Originally built on a series of off-shore islands as a refuge from the Lombards in the early Middle Ages, it was so stably constructed by the time of the Renaissance, that it has lasted until our time—when it is threatened by rising seas. I’m especially impressed with clean running water that flows into every building, despite the polluted and often smelly waters of the canals. Where are the pipes?

There are public wells in most of the squares, with metal lids firmly affixed to them. Nowadays, water is piped in from the mainland, and a huge amount of bottled water and water from the public fountains is consumed. Before 1884, however, Venetians drank filtered rainwater, which was collected from virtually every surface and stored below ground in cisterns.

I had brought my closeup lens with me and managed to hold my camera steady enough to take sharp photos of a number of these medallions, while wondering about what these named men, who governed for 13 years here and 9 years there, could have been like as individuals. Venice was not ruled by a few prominent families, like the Medicis in Florence, the Borgias in Rome, or the Gonzagas in Mantua.

Perhaps this was one of the sources of its long-lived power, which created so much wealth, much of which was spent in public projects. This tradition of continuous wealth is very much in evidence today, from the high-end shops to the motor boats that so many residents own–but not enough to crowd any of its waterways, or to need traffic lights. And it’s this wealth that I imagine to be the foundation of the near ubiquity of high artistic taste in the city.

Perhaps I idealize, but the delightful originality of design that one finds in the home furnishings and fashions bespeaks a sophisticated very comfortable clientele. The galleries are another matter, of course. I’ll return to them.

The books behind glass in the libraries mostly dated from the 18th Century and earlier. Many of the titles on the bindings were hand-written. Other were multi-volume histories of Venice, which were presumably in the Veneto dialect, although their titles were understandable enough. Other rooms displayed paintings, including large-scale scenes of naval battles and festivals, as well as many portraits, plus models of buildings and ships.

The Battle of Lepanto (1571) by Andrea Michele (aka Vicentino), from the late 16th Century. (Battle fought between Venice with its Spanish allies against the Ottoman Turks, in the Gulf of Patras, Greece.)

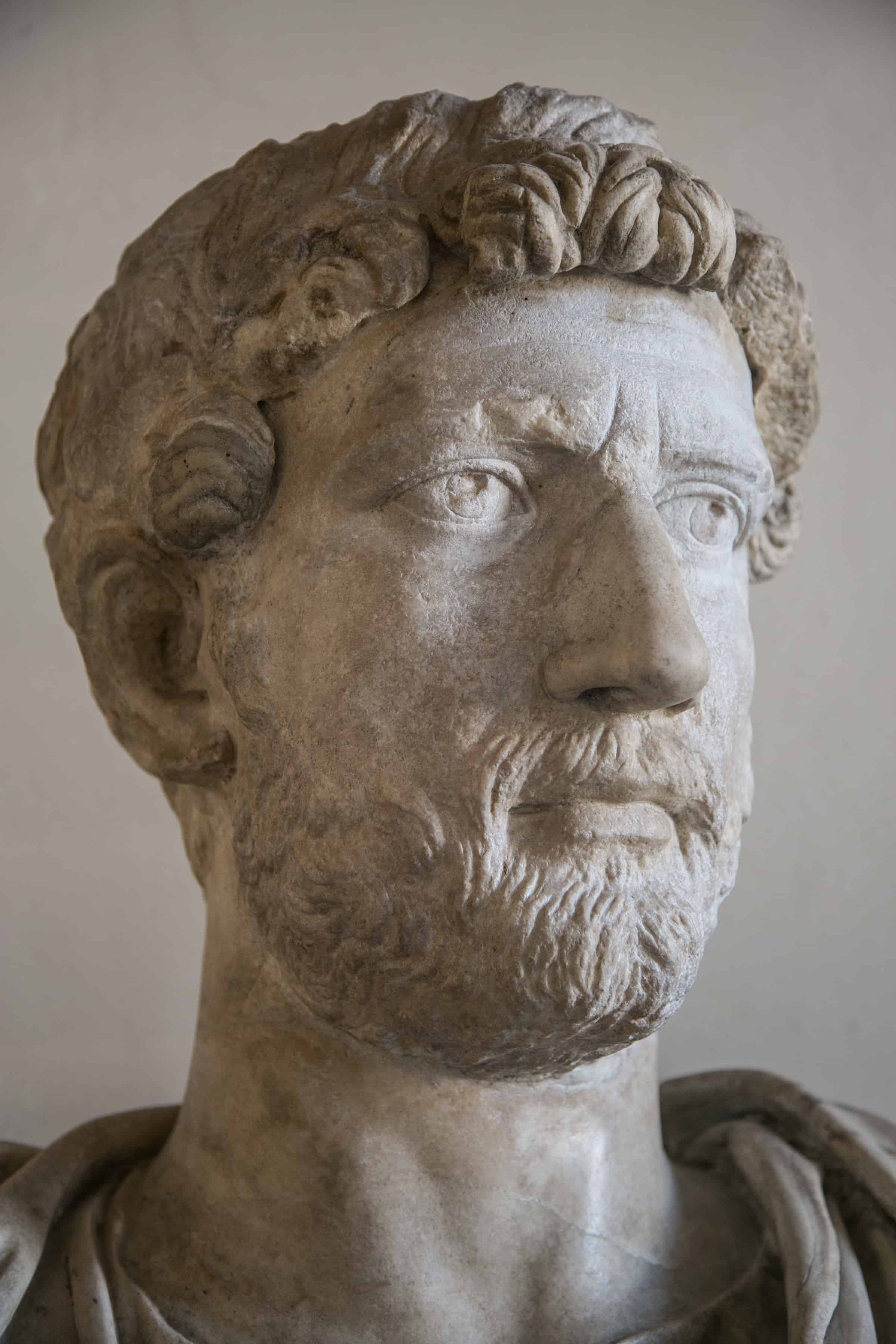

The archeological museum featured an extensive collection of imperial Roman portrait busts and statues, including Tiberias, the only representative of the Caesars, and the Flavians who followed them (photo: Bust of Emperor Hadrian, 76-138 CE). Every one of them was a face I could have seen at a Chamber of Commerce meeting back home–and they all spoke fluent Latin! There were also three near life-size statues of dead or dying Gauls, the conquered enemies of the Romans in Caesar’s time. Such museums really give one a sense of history that goes beyond names, dates, and important battles, and even beyond the contemporaneous biographies and historical narratives. One gets a sense of national will, arrogance, strength, and military risks taken. There was also an astonishing collection of fibulas, the huge “pins” that held the togas closed.

The Emperor Hadrian, portrait bust

Wounded Gaul.

Fibulas, the metal pins that held togas and other Roman clothing together.

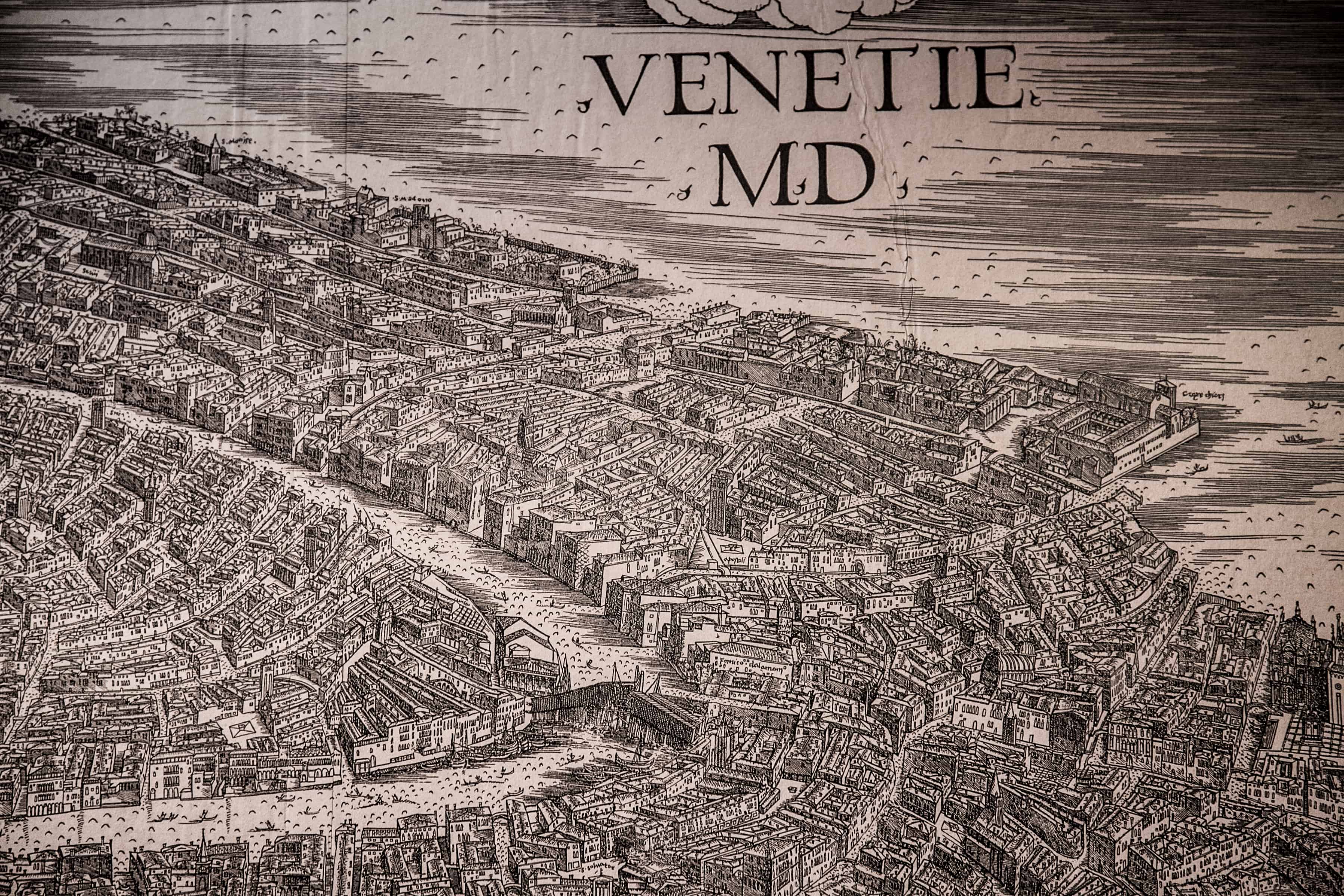

Back in the Venetian section, I was very impressed by a 20-foot long engraved map of Venice in 1500 (photo: detail), just below which were the plates that created the engraving. Apparently Venice was also a major center of printing and engraving during that time, serving the rest of Europe.

Engraved map of Venice, 1500 (detail)

The museum had been a private palazzo, that is, a rich family residence, and its interior decor gives the visitor a sense of the wealth and pomp of that small class that benefited from Venice‘s power in the world. It was only the male members of that class, of course, who were members of the Collegio and thus who could vote to elect the Doge. And it was exactly the Venice Collegio that gave our founders the idea for the Electoral College!

The most elaborate display room in the Museo Carrer. This must have been used as a ballroom when the building was a private palazzo in Venice’s imperial heyday.