Leaving Museo Carrer in the magical Ialian city of Venice, I headed for Palazzo Grassi, which housed half of the Damien Hirst show, Treasures from the Wreck of the Incredible. While I normally think of Hirst as a fashionable artist for the super-wealthy, stronger in audacity than in imagination (think of the full-sized shark in formaldehyde), this show completely turned me around on him, leaving me in awe of how he had audaciously undertaken a grand-scale project that embraces a large swath of the art of the ancient world and more, and which is fundamentally a huge (and deliriously expensive) joke.

But at first I didn’t know it was a joke. I had taken a peek at the catalogue in a bookstore near where I was staying and decided that the show was definitely worth seeing. Now I was threading my way through the calles and over the rios toward the Canal Grande, according to the directions I had called up on my phone.

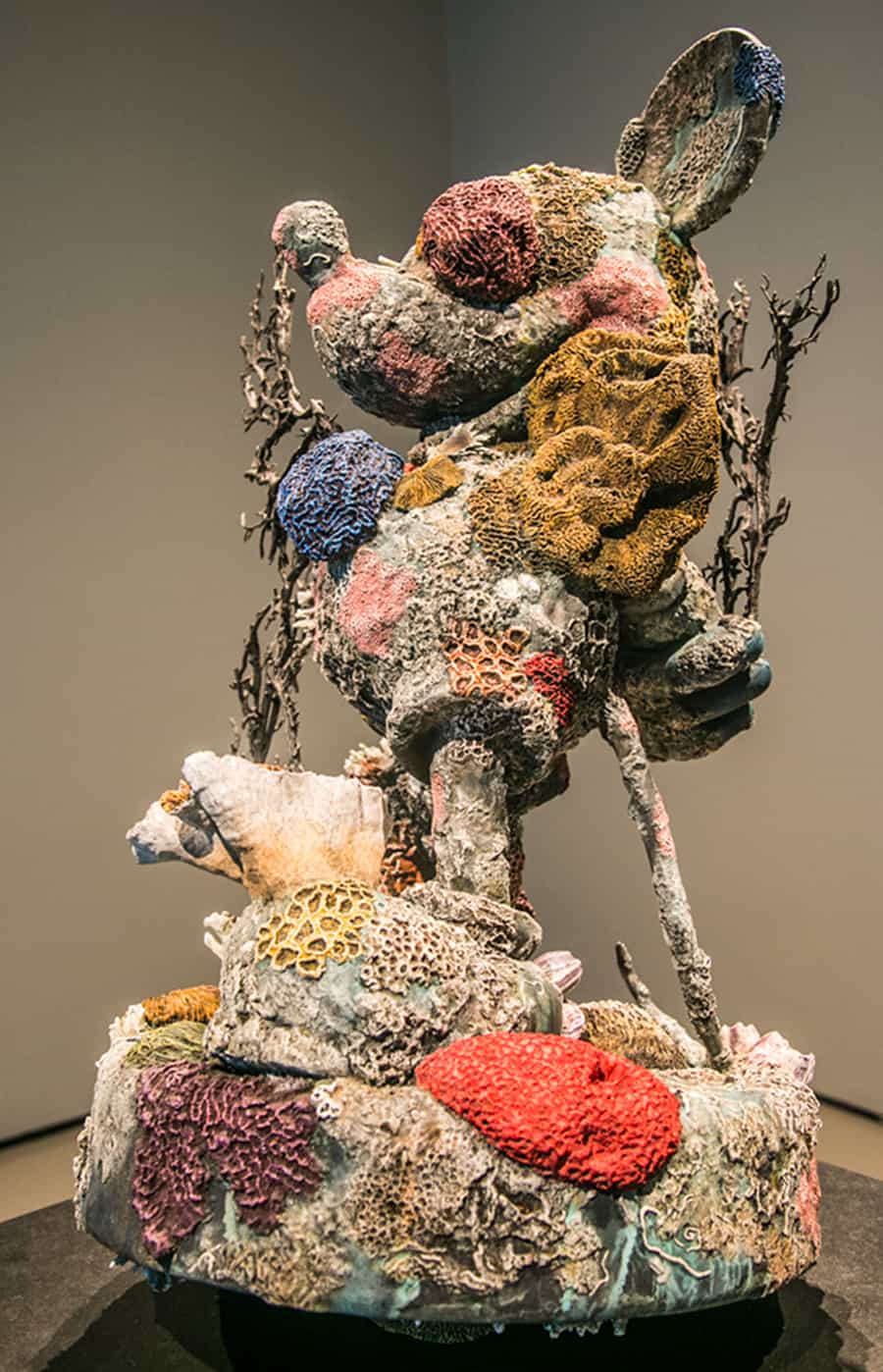

Arriving at the Palazzo, I was struck–as was everyone else–by the four-story faceless bronze statue of a naked man with reptilian claws, encrusted with the trappings of a coral reef, all in bronze. This was Hirst’s overture, indicating both the theme and the scope of the exhibition.

Central Figure at the Palazzo Grassi portion of Damien Hirst’s “Treasures from the Wreck of the Incredible”

The Palazzo honored my journalistic credentials, and I read the (fictional) background story of the exhibition: a freed slave in Roman times had amassed a considerable collection of world-wide art, put it all on a ship, and that ship, whose Greek name translated as “Incredible,” had foundered off the coast of East Africa some time in the 2nd or 3rd Century CE.

Its existence and its wreck had become a minor legend; no one knew if it was really true, until it was actually discovered in 2008. Its contents were recovered, and here they was. Two small theaters showed slides and movies of the underwater recovery process, with the pieces of all sizes being brought up from their resting place in a reef, and taken aboard ship.

The gold–and there was a lot of it–had not tarnished through the ages. The pieces included a Medusa head, various nude figures, an elephant skull, and smaller pieces, such as ancient metal purses, jewelry, weapons and coins from an immense hoard, most of them still encrusted with colorful reef material, including coral and barnacles. The elephant skull was labeled as that of a cyclops, and I was familiar with the notion that the cyclops legend had developed from the Greek colonial residents of Sicily thinking that the actual skulls of dwarf elephants (larger than human skulls) had belonged to a race of one-eyed giants.

Encrusted elephant skull mock-up.

Underwater dramatization of salvage of encrusted elephant skull (mockup).

Head of Medusa (mockup).

Head of Medusa, dramatization of salvage.

Then there was the encrusted statue of Mickey Mouse, and a completely barnacle-covered one of Goofy…the whole thing was a put-on, and a very VERY elaborate one. Hirst had created and directed everything, including the faked underwater recoveries. It was brilliant.

The show, however, went on to send up the whole field of archeology, by including pieces from such a range of cultures through time that would have been impossible to find at a single site: Egyptian, Celtic, Hebrew, Medieval Christian as well as ancient Greek and Roman. But Hirst wasn’t trying to deceive anyone, just to play an immense joke. In other parts of the show he presents sculptures in three stages of transformation, from smooth perfection to time-damaged reef-encrusted relics.

Encrusted Mickey Mouse—that gave the game away.

The Palazzo Grassi only had the space for a single huge sculpture. Its three floors surrounding the atrium colossus featured pieces no more than 6 feet tall. But Hirst was more ambitious than this. More three-story tall pieces were housed in the building called the Punta della Dogana, that is, the Venetian Customs House, located across the Canal Grande from the Piazza San Marco on the spit of the Dorsoduro section of town.

Leaving the Palazzo Grassi, I headed for the Accademia bridge, the only other crossing of the Canal Grande by foot other than the Rialto in the center of town. The Accademia bridge is a simple wooden structure, unlike the mostly covered stone bridge of the more famous Rialto. On my way, I made two stops.

The first was in a mask and costume shop that had a stronger sense of 18th Century authenticity than the others I had seen. Here the masks were all in black, along with three-cornered hats and capes. The designer was inside with a friend. He was a man in early middle age, dressed casually, looking more like a real estate agent than a fine craftsman of historical masks. But what should I have expected? A wheezing bent-over artisan out of The Old Curiosity Shop? He was probably younger than I was. They both welcomed me warmly. I took pictures, and we exchanged contact information.

Mask, mirror, lighting shop in Venice

Mask, mirror, lighting shop in Venice, selection of masks

Intense Serendipity & The Other Part of Damien Hirst’s Show

My next unplanned stop was one of the most memorable of my entire visit. The open door of what seemed to be a gallery or studio at Calle Malipiero 3084 in the San Marco district revealed a collection of sculptural and two-dimensional compositions that combined somewhat archaic images of the animal world with Medieval and Renaissance fragments and documents, as if a surrealist sensibility had been catapulted back in time three to seven hundred years ago. Visible forms from nature were the subjects of intense curiosity starting in the 16th Century, as attested by the work of Arcimboldo, for example. Before that, the artistic imagination focused on religious and mythological subjects, often with great invention (especially concerning the tortures of hell), as exemplified by the work of Hieronymus Bosch. This present artist, Gigi Bon (now in her 50s or 60s) draws from both traditions to fashion the playful confections that utterly captivated me. Her art-space was filled floor to ceiling with them, putting the visitor in a state of ecstatic imaginative overload.

She herself defines her gallery/studio as a kind of Wunderkammer, or Cabinet of Curiosities, but her works are not neatly arranged in display cases or hung on the wall: they explode all over the place. Like Hirst, she used past aesthetics as her resources, creating her own “antiquarian avant-garde.”

There is a romance to these ornate antique aesthetics that the modern sensibility perceives as refreshing, devoid of the commercial, the technological and photographically literal, as well as the free-form abstract.

International antiquarian avant-garde artist Gigi Bon

Gigi Bon’s work area in her studio gallery. Note rhinoceros on the back wall, left of center.

Very little space lies fallow in Gigi Bon’s studio gallery. Note the Lion of Venice on the right. Her art proudly glorifies her native city.

Gigi seemed to have a predilection for the rhinoceros: in her two-dimensional work she had introjected them into Renaissance cartography or into engravings of perspectival rooms completely covered with animal specimens, or mockups of 18th Century theaters, or had them cavorting around astrolabes.

In three dimensions, she created composite sculptures of them, some with eggs as abdomens, or emerging from eggs, or with horns that ended in the typical gondola comb-like prow ornament. They were clearly her artistic totem.

Her dense collection of Renaissance to 18th Century (Venice’s Golden Age) images already used heterogeneity to whisk the visitor forcibly out of the present and into a fantasy world of a remote and alluring imaginary, while the various avatars of her rhinoceroses provided delightfully off-balance notes of incongruity, that also served as a unifying and branding leitmotif.

Artist Gigi Bon surrounded by her creations. Gigi works in many modes, genres and media.

Pewter rhinoceros evoking the famous Dürer drawing, and one of Gigi Bon’s favorite motifs.

Gigi welcomed my interest in her work and showed me to her production studio in a room adjoining her storefront gallery. She had had shows throughout Europe and in the US, but didn’t think she would travel to the US again. I had to have her gorgeous hard-cover book.

When I showed her my Body Projections catalogue, she recognized me as a colleague, and I was appropriately flattered. We agreed upon an exchange, which amounted to a discount off her more expensive publication. It immediately became my most treasured acquisition of my entire trip. I was determined to add it to my baggage somehow, despite its weight.

I told her I was headed for the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. But Gigi advised me to visit the Accademia Gallery instead, Venice’s premier art museum. “You know well the things you’d see at the Guggenheim,” she said (we were speaking Italian). I had visited the Accademia on my first visit to Venice in 1967 at age 20, and I remembered the remarkable collection of Canalettos, depicting 18th Century Venice, its classical age, that the souvenir shops full of masks try to evoke. I thanked her for her advice, and we parted with promises to stay in contact.

I crossed the Accademia bridge, but the Accademia itself was closed–as of 2 pm on Mondays. So off I went to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. The setting is beautiful for this modest but strong collection of 20th Century works by Peggy’s friends, with a notable tilt towards Surrealism.

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, view from landing on the Grand Canal

And though Gigi was right about seeing art I had long been familiar with, it was still very satisfying to behold the originals of works I had mostly seen in reproduction, or works I had never seen by artists I knew and admired (like Chilean surrealist Roberto Matta, 1911-2002), or surrealist artists who were completely new discoveries.

The Dryads (1941) by Roberto Matta

The Dryads, detail

Still, there were many works I had never seen before, even brilliant Surrealist artists I hadn’t heard of. I knew little of Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) for example, the British-born Mexican surrealist and one of the last survivors of the original group of Surrealist artists of the 1930s. Her work Oink, They Shall Behold Thine Eyes (1959) is an oneiric image referring to the great Judaic mystical text, the Kabbalah:

Leonora Carrington: Oink: They Shall Behold Thine Eyes

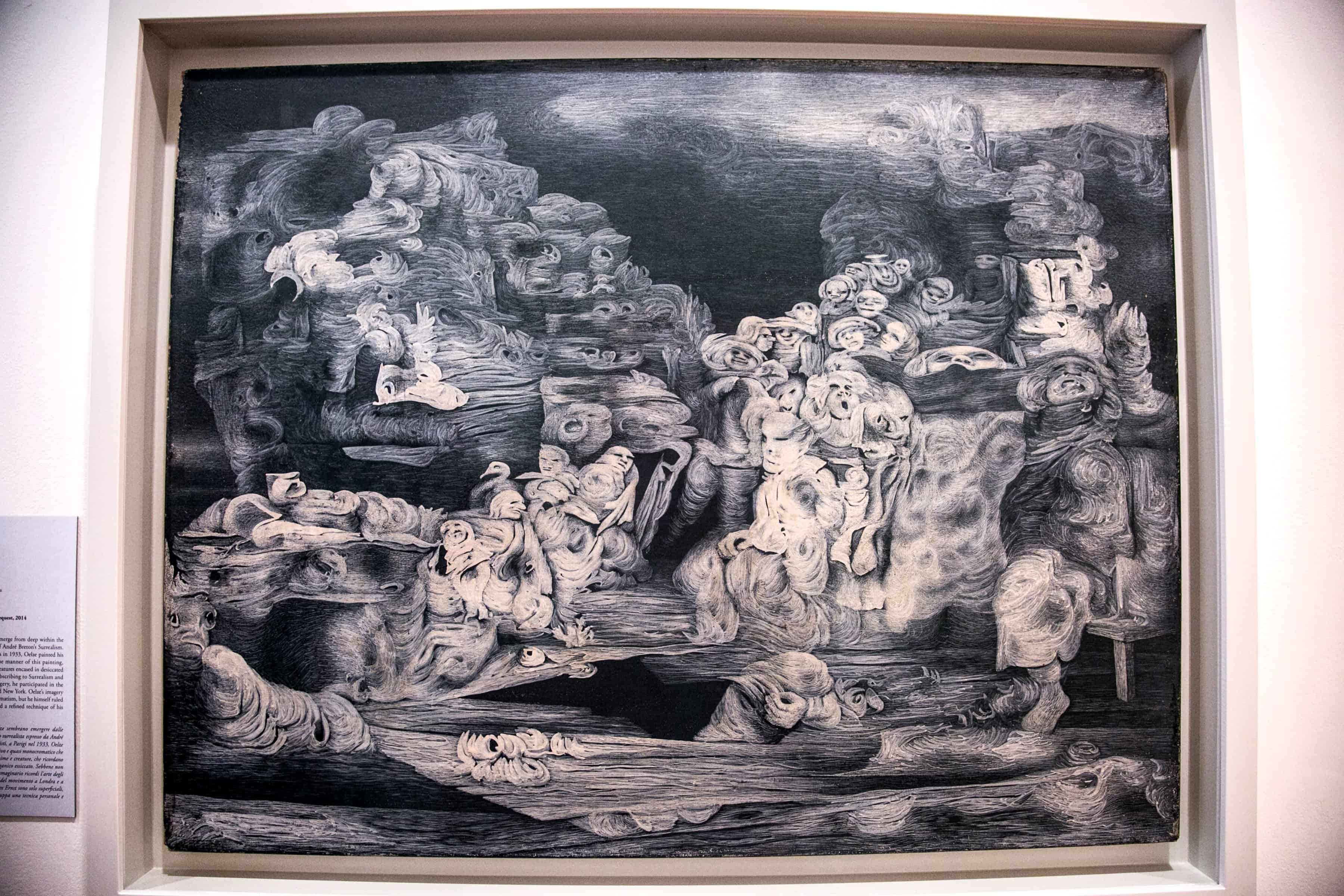

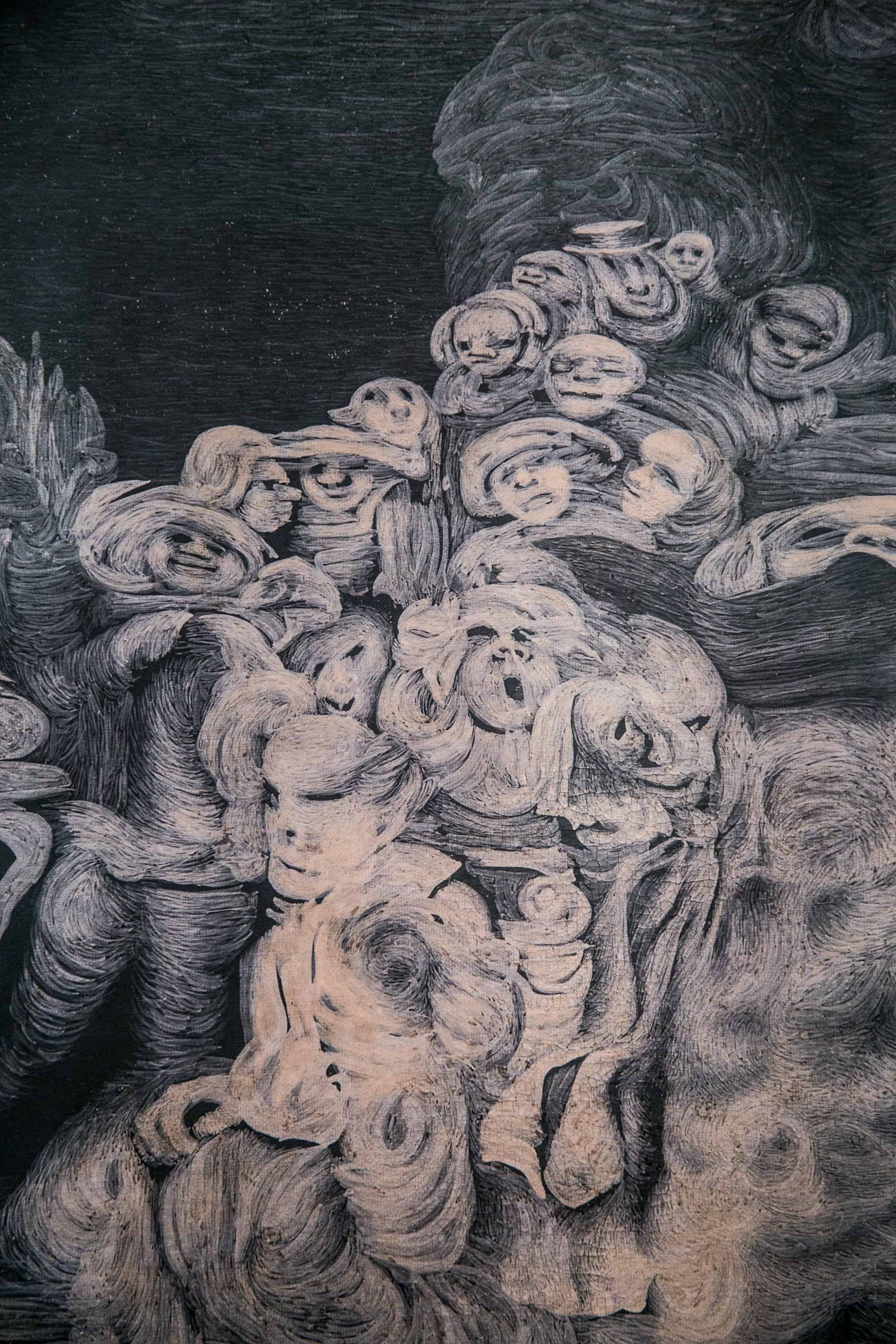

German visionary surrealist Richard Oelze (1900-1980) was a very satisfying discovery. Although he never formally joined the Surrealist movement and was sometimes considered an outsider artist, he showed with the Surrealists, and his work, drawing as it does, from his unconscious, lies squarely within their aesthetic.

Richard Oelze (1900-1980): The Sorry of Lost Agony (1948?)

The Sorrow of Lost Agony, detail

There was also a fascinating special exhibit of the work by artist Mark Tobey (192?-1976) whose signature style of the “living line” was one of engaging matrices that created highly nuanced textures, nothing like anything I had ever seen before, in art or in nature. No photography was permitted.

The grounds of the collection were extremely pleasant: a semi-shaded courtyard surrounded by trees (a rarity in Venice) and a stone wall, with Peggy’s grave (her dates: 1898–1979) in one corner, and garnished with stone sculptures.

Courtyard Garden, Peggy Guggenheim Collection

Sculptures in the garden courtyard of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

Peggy Guggenheim’s grave in the courtyard to her Collection

Leaving there, I stepped into a pop-up photo gallery to my immediate left, with a huge image of two male New York cops engaged in a deep kiss in the shop window. It was the Belair Fine Art Gallery (a Swiss-based company) featuring the trangressive staged work of Gérard Rancinan and Caroline Gaudriault, featuring beautiful models, selective nudity, some punk hairdos, and an undercurrent of violence–clearly in the mode of David LaChapelle (who was also exhibiting in Venice at the time), but with edgy political, even revolutionary themes—in contrast to LaChapelle’s preoccupations with Christ and chaos.

I showed the gallery attendant and his friend my work, and both were impressed. I left him a copy of my Body Projections catalogue, and he promised to send it to the owners of the gallery group. Finally, I had accomplished what I had brought all those samples with me for.

Gérard Rancinan & Caroline Gericault, Parody of Iwo Jima photograph and sculpture

Gérard Rancinan & Caroline Gericault, New York Streets

I arrived at the Punta della Dogana in less than 10 minutes. It was 5:15. I had 45 minutes to see the rest of the Damien Hirst show. Here is where the bulk of his monumental encrusted sculptures were on display. Here, too, he gave freer reign to his fantasy, less concerned with historical believability: many of his themes seemed to come from Marvel Comics. The most striking one was that of a muscular hero confronting a monster consisting of multiple cobra heads, with one big one in the middle.

Damien Hirst: Treasures from the Wreck of the Incredible (Punta della Dogana)

Staged underwater recovery of large statue

Cast of statue before the application of marine incrurstation

Another had a screaming man riding atop a giant bear. On a more modest scale was a nude woman walking with a lion, and a woman and a man chained naked to each other (being punished for adultery?) Hirst combined here, as he frequently did, voluptuous physicality, the colorful romance of the ruin as marine incrustation, and the “true-life adventure” of the huge richly saturated photographs of the underwater salvage operations.

Damien Hirst: Treasures from the Wreck of the Incredible

Damien Hirst: Treasures from the Wreck of the Incredible, photo of “salvage” operation.

There were also two rooms filled with display cases containing a mixture of “ancient” artifacts, that were pretty convincing when viewed individually, but their anachronistic juxtaposition betrayed the artifice: Muslim, Byzantine, Jewish, Irish Celtic, Meso-American, etc. all supposedly found in the wreck of his fictitious ship that foundered in the Fourth Century C.E., appropriately named the Incredible.

Artifacts “found” in the Wreck of the Incredible

There were also larger artifacts, whose corrosion seemed to point to the Bronze Age, including a shield that just might have come from the military paraphernalia of an Amazon warrior.

Military artifacts: Spartan style helmet, “Amazon” shield, various swords

Hirst also demonstrated his transformational studio process in this gallery, showing a statue in four phases: the perfect original, the damaged original, the encrusted damaged original, and the painted encrusted damaged original, which supposedly had lain for centuries at the bottom of the sea.

Before I saw this exhibition I had thought of Damien Hirst as a fashionable artist trading more on novelty than genius, but Treasures from the Wreck of the Incredible has forced me to revise that assessment. Hirst’s immense fictitious salvage operation is every archeology lover’s wet dream: hyper-romantic in its recovery of long-lost partially ruined artifacts that are by turns melodramatic, realistic, erotic, pop-cultural and hilariously anachronistic, it is full of faux authenticity that dissolves into mockery. It is a magnificent achievement.

It leads the visitor on an extensive treasure hunt that ends in laughter. Its considerable scope, diversity and exacting detail throughout place it among the great installations of our time—I can only think of one other of this magnitude, Matthew Barney’s super-serious meditation on sex and creation, his Cremaster Cycle (1994-2002), which was considerably larger and much less amusing.

In this post-modern age of fake news, when even our most trusted media no longer permit themselves to tell the whole truth (if they ever did), when hoaxes and deceptions are easily confused with factuality while attracting their own communities of true believers, Hirst’s invitation for us to look back seventeen centuries in wonderment that dissolves into laughter at his elaborate joke comes as welcome comic relief. It might even provoke us to imagine future generations looking back on the season of Trump with its chaos of lies and delusions that eventually devolved in…(what? another crash? worse?) with an ironic smile.

I left at 6:10 and walked back to my lodging. On the way, I stopped at a small bookstore and bought a Livre de Poche condensed edition of Giacomo Casanova’s autobiography (the original is over 1200 pages), originally written in French to reach a wider audience than his native Italian (which he considered to be the more expressive language). I had picked up the first of a 3-volume translation of the work at a sale in my town library. This had gotten me interested in Casanova (1725-1798), an immensely literate and well-traveled man, who composed Latin verse and wrote many other important works. Although known primarily as a serial seducer, he was also a bold adventurer and risk-taker, who spent time in a Venetian jail and became persona non-grata throughout Italy and in Poland. I wanted to read him in his original French, but I didn’t expect to run across his work in French outside of France. But he was a Venetian! And the place was filled with French tourists. This bookstore had a whole cubby-hole filled with his works in its French section. Leaving the bookstore, I walked across the alleyway and ate at a local tourist restaurant, bought a chocolate-covered canolo for 5 euros from a different restaurant, and returned to my lodging, where I shared it with the charming young Romanian woman who helped out there, and who was also an artist and good evening company.

The last morning I got up early which gave me time to photograph the Rialto bridge in virtual symmetry using its reflection in the window of the pier waiting area.

Rialto Bridge Reflection