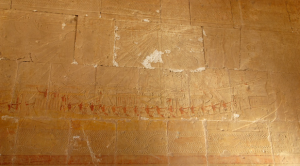

The scenes carved into a wall of the ancient Egyptian temple at Deir el-Bahri tell of a remarkable sea voyage. A fleet of cargo ships bearing exotic plants, animals, and precious incense navigates through high-crested waves on a journey from a mysterious land known as Punt or “the Land of God.” The carvings were commissioned by Hatshepsut, ancient Egypt’s greatest female pharaoh, who controlled Egypt for more than two decades in the 15th century B.C. She ruled some 2 million people and oversaw one of most powerful empires of the ancient world.

The scenes carved into a wall of the ancient Egyptian temple at Deir el-Bahri tell of a remarkable sea voyage. A fleet of cargo ships bearing exotic plants, animals, and precious incense navigates through high-crested waves on a journey from a mysterious land known as Punt or “the Land of God.” The carvings were commissioned by Hatshepsut, ancient Egypt’s greatest female pharaoh, who controlled Egypt for more than two decades in the 15th century B.C. She ruled some 2 million people and oversaw one of most powerful empires of the ancient world.

The exact meaning of the detailed carvings has divided Egyptologists ever since they were discovered in the mid-19th century. “Some people have argued that Punt was inland and not on the sea, or a fictitious place altogether,” Oxford Egyptologist John Baines says. Recently, however, a series of remarkable discoveries on a desolate stretch of the Red Sea coast has settled the debate, proving once and for all that the masterful building skills of the ancient Egyptians applied to oceangoing ships as well as to pyramids.

Archaeologists from Italy, the United States, and Egypt excavating a dried-up lagoon known as Mersa Gawasis have unearthed traces of an ancient harbor that once launched early voyages like Hatshepsut’s onto the open ocean. Some of the site’s most evocative evidence for the ancient Egyptians’ seafaring prowess is concealed behind a modern steel door set into a cliff just 700 feet or so from the Red Sea shore. Inside is a man-made cave about 70 feet deep. Lightbulbs powered by a gas generator thrumming just outside illuminate pockets of work: Here, an excavator carefully brushes sand and debris away from a 3,800-year-old reed mat; there, conservation experts photograph wood planks, chemically preserve them, and wrap them for storage.

Not long afterward, another cave entrance emerged from the loose sand underneath a coral overhang. Inside was a chamber that made the first discovery look cramped: a gallery about 15 feet across, some 70 feet long, and tall enough for a short man to move around freely. The cave’s entrance was reinforced with old ship timbers and reused stone anchors, the first conclusive evidence of large-scale Egyptian seafaring ever discovered.

More planks had been reused as ramps, and the cave floor was covered in wood chips left by ancient shipwrights. Other debris included shattered cups, plates, and ceramic bread molds, as well as fish bones. The cave’s dimensions resembled those of standard Egyptian workers’ barracks such as those found near the pyramids at Giza.

Over the past seven years, Fattovich and Bard have uncovered the hidden remnants of the ancient harborside community, which overlooked a lagoon more than a mile across. In addition to eight caves, they have found remains of five mud-brick ramps that might have been used to ease ships into the water and a shallow rock shelter used for storage and cooking. They work in the winter, when temperatures in the desert hover in the high 70s and the poisonous vipers that infest the caves are hibernating. Neither scientist was eager to spend much time in the caves: Fattovich describes himself as claustrophobic, and Bard has a deep-seated fear of snakes.

Evidence connecting Mersa Gawasis to Punt piled up both inside and outside the caves. A few hundred yards from the cliffs, piles of crumbled stone and conch shells a few feet high are evidence of altars the seafarers built north of the harbor entrance. They included stones carved with inscriptions that specifically mention missions to Punt. Timbers and steering oars similar to those on ships depicted in Hatshepsut’s wall carvings were recovered in sand both inside and outside the caves. Many of the artifacts were riddled with telltale holes made by saltwater shipworms. The team even found fragments of ebony and pottery that would have come from the southern Red Sea, 1,000 miles away.

As if that weren’t enough, among the remnants of 40 smashed and empty crates found outside one cave were two sycamore planks marked with directions for assembling a ship. One of them bore an inscription still partly legible after 3,800 years: “Year 8 under his majesty/the king of Upper and Lower Egypt … given life forever/…of wonderful things of Punt.”

“It’s really rare that you have all the evidence that fits together so nicely,” Bard says. While the windfall of Mersa Gawasis artifacts has answered some questions, it has raised others. For instance, how did the expeditions to Punt actually work, and how did the Egyptians construct vessels that could make a round-trip voyage of up to 2,000 miles?

Squatting in the humid heat of one of the Mersa Gawasis caves, Cheryl Ward unwraps a huge chunk of cedar as thick as a cinder block. Salt crystals on the wood glitter in the light of her headlamp. Ward turns the block in her hands and explains that it was once part of a plank from a ship’s hull. From its width and curvature, she estimates the original ship would have been almost 100 feet long. “The size and magnitude of this piece are larger than anything we have for any [other] Egyptian ship, anywhere,” she says.

Ward, a maritime archaeologist at Coastal Carolina University in Conway, South Carolina, spent three years building a full-scale reconstruction of a ship that would have docked in the lagoon of Mersa Gawasis. Ward has determined that unlike modern vessels, which are built around a strong internal frame, the Egyptian ship was essentially one giant hull. The curious construction meant that the craft required much larger timbers for strength. The wood was also cut thicker, with enough extra width to compensate for damage by shipworms. Some of the ship parts preserved in the Mersa Gawasis caves are more than a foot thick. “One of the features of Egyptian architecture is overbuilding,” Ward says. “You can see similar safety features in the construction of these ships.” Ward’s archaeological experiment needed 60 tons of Douglas fir as a stand-in for the Lebanese cedar used by the ancient Egyptians.

Toward the back, a padlocked plywood door seals off an adjacent cave. As soon as the door is unlocked, a sweet, heavy, grassy smell like that of old hay wafts out, filling the area with the scent of thousands of years of decay. In the thin beam of a headlamp, one can make out stacked coils of rope the color of dark chocolate receding into the darkness of the long, narrow cave. Some of the bundles are as thick as a man’s chest, and the largest may hold up to 100 feet of rope.

The rope is woven from papyrus, a clue that it may have come from the Nile Valley, where the paperlike material was common. Archaeologists found it neatly, professionally coiled and stacked, presumably by ancient mariners just before they left the shelter of the cave for the last time.

Boston University archaeologist Kathryn Bard and an international team have uncovered six other caves at Mersa Gawasis. The evidence they have found, including the remains of the oldest seagoing ships ever discovered, offers hard proof of the Egyptians’ nautical roots and important clues to the location of Punt. “These new finds remove all doubt that you reach Punt by sea,” Baines says. “The Egyptians must have had considerable seagoing experience.”

Digging in Egypt was supposed to be a side project for Bard and her longtime research partner Rodolfo Fattovich, an archaeologist at the Orientale University of Naples. The two scholars have spent much of their careers excavating far to the south of Mersa Gawasis, uncovering the remains of ancient Axum, the seat of a kingdom that arose around 400 B.C. in what is now northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. When a 17-year civil war in Ethiopia ended in the early 1990s, Fattovich and Bard were among the first archaeologists to return to digging there.

Neither is a stranger to sketchy situations. Fattovich was working in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, in 1974 when a coup toppled the country’s monarchy. Bard, who has degrees in art and archaeology, spent a year making the sometimes dangerous overland trip from Cairo to Capetown in the mid-1970s. She often wears a red T-shirt reading “Don’t Shoot—I’m an Archaeologist” in more than a dozen languages.

Their time at Axum was cut short by another war. In 1998 fighting between Ethiopia and Eritrea flared up while Fattovich and Bard were excavating a collection of tombs just 30 miles from the border. The archaeologists were forced to flee, driving more than 200 miles south through the Simian mountains of Ethiopia on a one-lane dirt road.

With the instability in Ethiopia, Fattovich and Bard were unsure if they would be able to resume digging there. They decided to head to Egypt, where archaeologists had long been searching for evidence of maritime trade links between that nation and the possibly mythical kingdom of Punt. Fattovich, a voluble Italian with a bum knee, remembered reading about some scattered rock mounds found in the 1970s along the Red Sea. “We decided, why not go investigate?” Fattovich says. “But when we got there, the site looked very disappointing. There were just a few shrines, nothing impressive.”

Beginning in 2002, they spent several weeks each year searching the coastal cliffs and the dried-up lagoon for signs of a harbor that might have sheltered merchant ships like those depicted in Hatshepsut’s wall carvings. Then, on Christmas morning in 2004, Bard was clearing what she thought might be the back wall of a rock shelter when she stuck her hand through the sand into an open space. Clearing away the drifts of sand and rock revealed a hemispherical cave about 16 feet across and 6 feet high. Its entrance was a carved rectangular opening, clearly not a natural formation.

Inside, the archaeologists found shattered storage jars, broken boxes fashioned out of cedar planks, and five grinding stones. A piece of pottery inscribed with the name of Amenemhat III, a pharaoh who ruled Egypt around 1800 B.C., helped the team pinpoint the cave’s age.

The above was taken from a much larger piece over at Discover Magazine. For the entire article including images and more, click here.

Photo Credits:

Image 1: A relief at the temple of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut in Luxor, Egypt, carved ca. 1480 B.C., shows a merchant ship on a trading expedition. Vessel artifacts match this depiction —

Stephane Begoin

Image 2: Coastal Carolina University archaeologist Cheryl Ward makes a scale drawing of the remains of an oar blade — Victoria Hazou

Renee Blodgett is the founder of We Blog the World. The site combines the magic of an online culture and travel magazine with a global blog network and has contributors from every continent in the world. Having lived in 10 countries and explored over 90, she is an avid traveler, and a lover, observer and participant in cultural diversity. She is also the founder of the Magdalene Collection, a jewelry line dedicated to women’s unsung voices and stories, and the award-winning author of the bestselling book Magdalene’s Journey

She is founder of Blue Soul Media and co-founder of Blue Soul Earth as well as the producer and host of the award-winning Blue Soul CHATS podcast, that bridges science, technology and spirituality. Renee also founded Magic Sauce Media, a new media services consultancy focused on viral marketing, social media, branding, events and PR. For over 20 years, she has helped companies from 12 countries get traction in the market. Known for her global and organic approach to product and corporate launches, Renee practices what she pitches and as an active user of social media, she helps clients navigate digital waters from around the world. Renee has been blogging for over 16 years and regularly writes on her personal blog Down the Avenue, Huffington Post, BlogHer, We Blog the World and other sites. She was ranked #12 Social Media Influencer by Forbes Magazine and is listed as a new media influencer and game changer on various sites and books on the new media revolution. In 2013, she was listed as the 6th most influential woman in social media by Forbes Magazine on a Top 20 List.

Her passion for art, storytelling and photography led to the launch of Magic Sauce Photography, which is a visual extension of her writing, the result of which has led to producing six photo books: Galapagos Islands, London, South Africa, Rome, Urbanization and Ecuador.

Renee is also the co-founder of Traveling Geeks, an initiative that brings entrepreneurs, thought leaders, bloggers, creators, curators and influencers to other countries to share and learn from peers, governments, corporations, and the general public in order to educate, share, evaluate, and promote innovative technologies.