Spend any amount of time in Barcelona and the chances are that beneath the Mediterranean façade of frolics and frippery, you will pick up on a much darker side of its history. This is, quite literally, under the surface – in the over 1,800 air raid shelters built underground during the Spanish Civil War.

Barcelona Under the Bombs

The war, which lasted from 1936 to 1939, had a particularly cataclysmic effect on the Catalan capital. In fact, Barcelona has the dubious accolade of being the first city in Europe to have had its civilian population systematically bombed. Both a front and a rear-guard at the same time, the city presented the perfect guinea-pig scenario for the aggressors.

The aerial attacks lasted two years and killed more than 2,000 of Barcelona’s civilians in that time. The bombings were in many ways a training exercise for the subsequent bombing tactics of the Second World War, which started in the same year the Spanish Civil War came to an end.

This experimentation in the techniques of warfare even earned its own chilling neologism – ‘urbicide’.

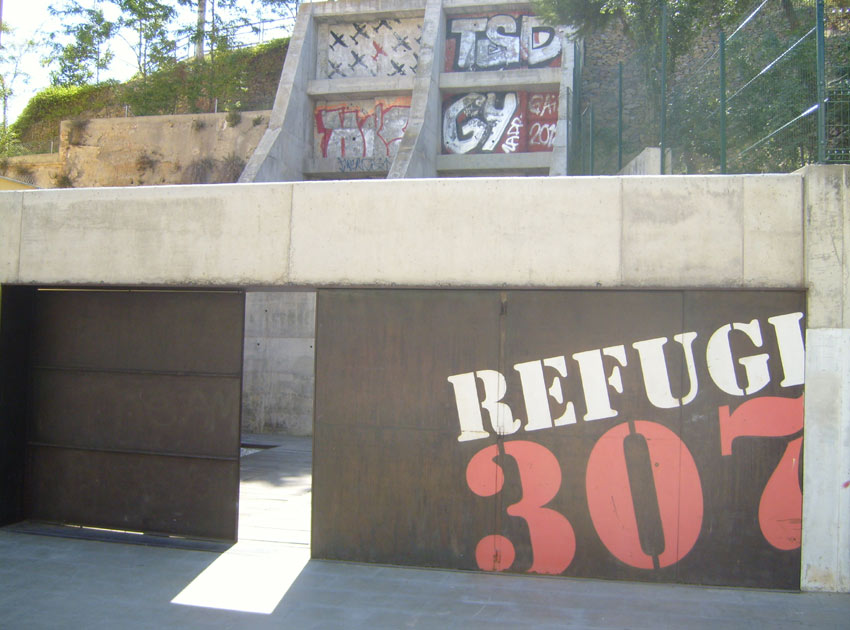

I had heard of the underground safety network in passing, and was even more interested when I heard that one of few shelters open to the public is in my own Barcelona neighbourhood, Poble Sec. On a scorching August morning I accompanied my friend and neighbour Eva to Refugio 307, on Nou de la Rambla, for a guided tour of this large subterranean labyrinth.

Going underground

What is immediately apparent is that no. 307 was a shelter far from the norm. Most of the 1,800 shelters, our guide tells us, had to be dug out of the ground – downwards. There were some city townhouses with air raid shelters in their basement, but mostly, it was a case of grab your shovel. And people did, partly organised by the Generalitat (Catalan government) but largely left to build the shelters of their own accord with whatever resources they could muster.

This particular refuge was built thanks to the charity of a Poble Sec local, who has remained anonymous. Not because the records are lacking, but because his family fear reprisals to this day.

This is one of the first facts we’re hit with before we enter the stone passageways, and it takes me a minute to fully assimilate the significance of the statement.

Here we are in a democratic country in western Europe, in the 21st century. But names have to remain secret in case…what? All of a sudden I feel that in my naiveté, I have spent the last 15 months living here in the mistaken notion that the city’s past is negligible. We bow our heads to enter the labyrinth and I feel a flush of shame.

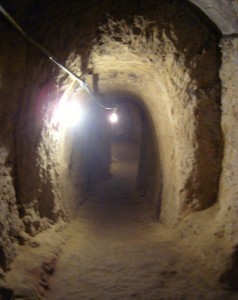

The shame quickly turns to awe and admiration. Battle-axed into the bedrock of Montjuïc hill lie 400 metres of vaulted tunnels, with crudely smoothed walls painted white in a deliberate attempt to combat claustrophobia. Initially, near the entrance, all bends are curved, to make it easier for the injured to be ferried in on stretchers.

Refugio 307, we learn, was a bit of a privileged spot, as air raid shelters go. Rather than digging down, Poble Sec locals were able to dig in – straight into the heart of Montjuïc mountain. The mountain has long been thought of as a spiritual source, and obligingly produced a source of running water that allowed the residents to install a plumbing system (of sorts).

Lit inside by oil lamps, the shelter had capacity for 2,000 people sat on wooden benches. But there was no ventilation (people feared chemical warfare) and consequently, you only had around two hours at a time inside before the air began to run out. Usually, this was adequate…until March of 1938, which saw the most protracted bombardment yet. For almost three days straight, Mussolini’s planes flew back and forth from their refuelling station on Mallorca, dropping 44 tons of bombs at random over Barcelona’s population.

Every two hours, the attack would begin again, meaning that locals were confined to the shelters for the duration. Normally when the air raid siren sounded you had, on average, less than two minutes to gather up your family and run to the nearest shelter. (Our guide tells us that people used to take their cue from dogs and chickens, which would start to become agitated long before humans picked up on the looming threat.) On this occasion, though, the sirens were useless – no-one could tell if they signalled the beginning or end of yet another attack.

Every two hours, the attack would begin again, meaning that locals were confined to the shelters for the duration. Normally when the air raid siren sounded you had, on average, less than two minutes to gather up your family and run to the nearest shelter. (Our guide tells us that people used to take their cue from dogs and chickens, which would start to become agitated long before humans picked up on the looming threat.) On this occasion, though, the sirens were useless – no-one could tell if they signalled the beginning or end of yet another attack.

“And I heard you scream/from the other side of the mountain…”

Despite the venue’s attempts to recreate something of the conditions of the time, with a sound track of sirens and bombs playing faintly in the background, it is of course impossible to imagine what Poble Sec residents must have felt. This district was particularly devastated by the aerial attacks, and plenty people emerged from the shelter time after time to find that their home had been razed to the ground in the meantime.

The personal and communal catastrophe is something our guide doesn’t gloss over.

She leads us through to the belly of the mountain, where, hacked into the rock is the ‘infirmary’. In reality, it’s a cave, with the remnants of a shelf chiselled into the stone. Touchingly, or perhaps practically, people here had made an attempt to pave the ground rather than leave it as the normal mud. Many residents suffered panic attacks during the course of the bombings – hardly surprising, when you imagine a dark, dank environment with fighter planes screaming overhead and both children and adults screaming in the vicinity. Since all the doctors were off at the front, ‘nurses’ volunteered to staff the infirmary – essentially local teenage girls off the streets.

House Rules:

There are touches of farce, of course, as well.

Our guide points out a plaque on the wall that spells out the topics that were off-limits inside the sanctuary.

- No politics (most folk taking shelter were on the side of the Republicans – but not all)

- No religion (probably goes without saying)

- No sleeping (wastes oxygen)

- No animals (leave your chicken at home – the guy next to you might not have eaten meat for six months)

- No furniture (looters used to raid houses while people were sheltering)

- No football (!)

And as the tour ends, our small party emerges blinking back into the sunlight, looking a little dazed in more ways than one. It’s been a sobering start to the weekend, and it leaves me wanting to find out more about the lives of the locals of my neighbourhood over the last century.

GuiriGirlinBarca is written by native Scot Julie Sheridan, who left Edinburgh’s haar-stricken hills for the slightly sunnier shores of Barcelona in April 2011. Armed with a big red emigrating suitcase (called La Roja) she arrived in the Catalan capital without knowing a soul, or indeed any Catalan. Her blog is an honest account of the ups and downs of life abroad as a single woman, including now not to get stalked by men and how to avoid unfortunate incidents with hamsters on bank holidays.