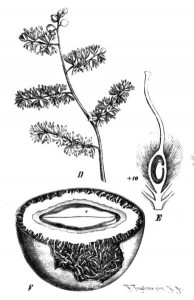

From food to fragrance, virtually no part of the sweet detar tree (Detarium microcarpum) goes unused. Astudy of the Mare aux Hippopotames Biosphere Reserve in western Burkina Faso identified the tree as one of six multi-use species “most appreciated by people” and thus “most important”. Two varieties of the species exist. The tall, forest variety produces bitter fruit while the shorter savannah variety produces a sweet, green fruit that is particularly popular in West Africa. The brown pods of sweet-sour fruit have the shape and size of apricots but a shell and pulp akin to its relative the tamarind.

Usually eaten fresh by children, the fruit is sometimes sun-dried then sold in markets. The fruit is boiled with jackalberry and black plumand concentrated to make fruit leathers in northern Nigeria, while in Sierra Leone, it’s made into a drink. Detar is higher in vitamin C than guava, and has a very good shelf life. It can be returned to its fresh state if it dries out by soaking it in sugar water, and the liquid by-product makes a fruity drink.

Boiling the fragrant seed breaks down the seedcoat to expose a kernel rich in essential amino acids and fatty acids, which is pounded into ofo flour in Nigeria and used to thicken egusi soup. Alternatively, cooking oil is extracted from the kernels by crushing them, with the by-products of this process used as an animal feed. When the seeds are not eaten, they are strung together to make fragrant necklaces.

The fragrance of other parts of the tree is useful as well. If the bark is damaged, a sticky, fragrant gum is secreted that is used to deter mosquitoes. Heated roots produce a sweet scent that is used as a perfume by women in Sudan, and as a mosquito repellent in Chad.

Resistant to moisture, weathering, and pests, the dense, hard wood is workable and thus highly desirable for carpentry and joinery when making houses, boats, and fences. The wood is also sought for firewood and charcoal since it lights quickly, even in the presence of moisture.

The bark, leaves, and roots help to treat a variety of ailments throughout West and Central Africa. Boiled powdered bark is used as a painkiller, fresh bark or leaves are used to dress wounds to prevent infections. In Mali, the bark is used to treat measles and hypertension while the leaves or roots are used to treat meningitis and cramps in people and diarrhea in cattle. The fruit pulp is used in Burkina Faso to treat skin infections, whereas in Niger and Togo the fruit is used to treat dizziness. In Senegal, the leaves mixed with those of other trees and milk is used to treat snakebites, while in Benin the leaves are boiled to treat fainting and convulsions.

The tree itself is heat and drought tolerant and capable of thriving on infertile sites. With its many uses, the tree would be a good candidate for reforestation of degraded lands.

Danielle Nierenberg, an expert on livestock and sustainability, currently serves as Project Director of State of World 2011 for the Worldwatch Institute, a Washington, DC-based environmental think tank. Her knowledge of factory farming and its global spread and sustainable agriculture has been cited widely in the New York Times Magazine, the International Herald Tribune, the Washington Post, and

other publications.

Danielle worked for two years as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Dominican Republic. She is currently traveling across Africa looking at innovations that are working to alleviate hunger and poverty and blogging everyday at Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the Planet. She has a regular column with the Mail & Guardian, the Kansas City Star, and the Huffington Post and her writing was been featured in newspapers across Africa including the Cape Town Argus, the Zambia Daily Mail, Coast Week (Kenya), and other African publications. She holds an M.S. in agriculture, food, and environment from Tufts University and a B.A. in environmental policy from Monmouth College.