My traveling companion Barbara is a great animal lover, so she booked us two nights at the Nairobi Tented Camp in the heart of Nairobi National Park on the edge of Kenya’s capital. It was not cheap, but we were treated royally. We each had a tent with a full size bed to ourselves. We entered by zippered door.

There was an adjoining bathroom with a modern chemical toilet and sink. The shower was fed from an elevated basin. You pulled a cord, and that let out the water. Strung rawhide replaced wood in the sink structure, and the basin lights were electrified kerosene lanterns. The lighting at night was especially soothing.

Beautiful red, orange and black rugs in traditional designs framed the furniture in the fabric rooms dominated by the ubiquitous tan of the tent canvas. Cut flowers supplied colorful accents. The common lounge offered plush sofas and easy chairs, and a collection of illustrated magazines with articles on the heroic days of African exploration in the late 19th and early 20 Centuries. Everything was extremely comfortable.

We ate at our own table in the dining tent, where the food was delicious at all times. There was always a tall man in traditional robes and sandals there with a flashlight to escort us from the dining tent to our sleeping tents, and to chase away the wart hogs that sometimes wandered into camp.

During the day you could sit out on your shaded veranda and watch the warthogs, kept at a safe distance, or catch sight of a money in a nearby tree. But who had time to sit around?

We began our first day with a visit to the Baby Elephant Orphanage, which has rescued 190 baby elephants orphaned by poachers or natural causes over their 37-year existence. Barbara even adopted one of them ($50/year).

We took two safari tours with a wonderful driver and guide whom they provided. Although we didn’t see any big cats, the flock of ostriches was thrilling, as was the grazing zebras and the lone rhino.

The great thrill of being in the Camp was the early morning safari we took the second day we were there. Leaving at 6:30 am, before the sunrise, we saw giraffe both close and far away, many zebra, buffalo, guinea fowl, crested cranes, and impalas, all against the misty background of the savannah. This is not the jungle. Kenya has rain forests, but they’re elsewhere. This was woodland and savannah, the very combination of environments that provoked our human evolution as bipeds.

When the earth cooled and the jungles receded, leaving large areas of grassland punctuated by woodland, it was advantageous to be able to walk on two legs. The great apes had done well in the jungle, where the trees are close together, evolving the opposing thumb on both hands and feet for grasping the branches.

But the savannahs made the opposing thumb on the feet useless, and made walking and running more necessary. In addition, there were now large ungulates, ruminants, who had evolved to turn the ow-nutrition cellulose of the grasses into their prime sources of food. Early humans learned to hunt these fleet and often dangerous creatures, which increased his and her protein sources.

When I visited the Kenya National Museum later that day, I saw the discoveries of our hominid ancestors that had been made in Kenya—quite a few of them—displayed in an excellent exhibit, that included more history of the discoveries themselves than does our New York Museum of Natural History.

It also had stuffed megafauna, including the necessary yawning hippo, as well as an extensive collection of stuffed birds.

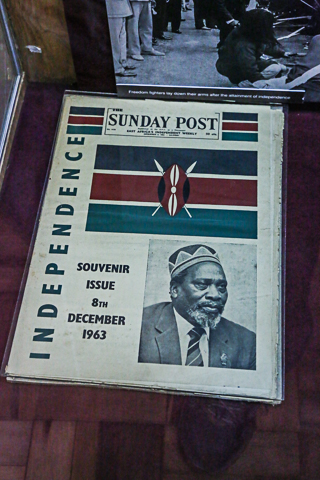

But it was also a historical museum, documenting the struggle for independence from Britain with newspapers from the era and an art museum, with fine contemporary artists from various tribes including the Yoruba. One artist was having an opening, and his female relatives dressed up in traditional Yoruba costume. I managed to line them up for a group portrait, that I later sent to the artist.

The highlight for me—though perhaps not for everyone—was the personal tour of the huge Kibera Slum. Billed as “The Friendliest Slum in the World,” on its website, I booked it before leaving the US. So I got a taxi ride into Nairobi proper to the edge of the slum, where I met Philip, my guide. I was hoping that this tour would give me a sense of real life of a large portion of the Kenyan population, and it did that and more.

Kibera, which extends over 4 square kilometers and is home to 1.2 million people, was originally forest land allocated to people who had come from rural areas to work in Nairobi. Over the decades the trees were cut down and shanties were erected, creating the sea of rusted corrugated iron that one sees today from above.

The streets are dirt, mud and stone, but passable, slowly, by cars. The overwhelming impression, however, is of bustling commerce.

People work their stalls and live in the back rooms, and they sell everything needed for their lives: vegetables, meats, piles of sardines, oceans of charcoal (their heating source, since there is no natural gas delivered and very little electricity), beauty products, cell phone products, small restaurants, beauty parlors, clothing of all sorts, toys, household goods, and even a photo studio.

I was the only one on the tour that day. My guide Philip told me that many of Kibera’s residents were offered public housing, but they refused, since it would take them away from their friends and require a commute—and an extra rent—to maintain their shops.

He also brought me to a center for women with HIV, where I spoke to one of the residents. She told me she had contracted HIV from a dirty needle during childbirth, and her husband had then rejected both her and her baby, who was there and, of course, delightful. The woman made crafts and jewelry to support the center, which got along on about $24,000 per year.

Philip also took me to bone factory, where jewelry and other decorative objects were made from the bones of cows, pigs, sheep and other available animals (not humans, they were at pains to tell me). It was a successful enterprise in the heart of the slum.

My daughter Nora informs me that slums afford livelihoods, albeit difficult ones, to their residents that the rural poor do not have access to.

There were children everywhere: playing games, swinging on string swings, helping at the shops, and just wanting to be photographed.

There was a community organization and a photographic studio, where my guide Philip posed before the colorful background

I made it back to the Park through horrendous Nairobi rush hour traffic—there are no highways as we know them in Nairobi. Infrastructure is terrible, and the city acquires more and more cars.

Dinner was delicious, as usual, and the serving staff made a point of folding our cloth napkins into a different shape for each meal. One of the shapes was an open collared shirt.

We left for the airport at 5 the next morning for our flight to Antananarivo, Madagascar.

While a safari and luxe glamping experience is no doubt a romantic one, it’s also a great experience for kids, when planning your next family travel trip.