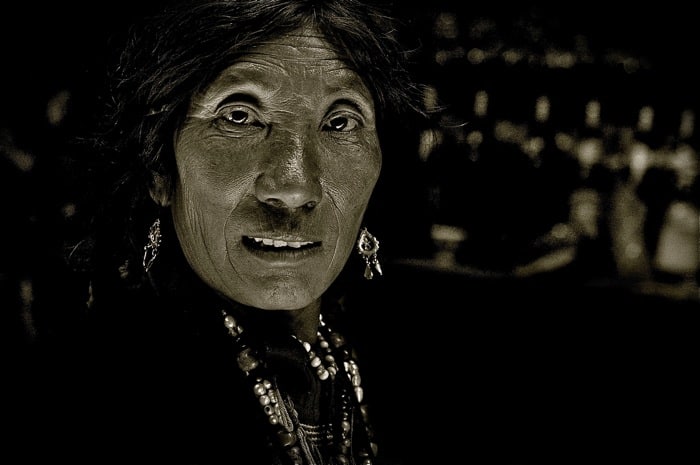

A nomadic head-woman, who depends on pashmina goats to remain autonomous. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

Interview with Himalayan explorer Jeff Fuchs

I MET OTTAWA-BORN explorer Jeff Fuchs several years ago at a tea shop in Toronto where he was giving a talk about Puerh tea from China and promoting his book, The Ancient Tea Horse Road. I was instantly smitten. The event combined my favourite beverage (tea), my favourite part of the world (the Himalayas) and an adventurous travel tale told by a charismatic explorer. It just doesn’t get any better, for me.

Jeff has lived for most of the past decade in Shangrila, northwestern Yunnan, upon the eastern extension of the Himalayan range where tea and mountains abound. His work centres on indigenous mountain cultures, oral histories and an obsessive interest in tea. His book The Ancient Tea Horse Road details his eight-month ground-breaking journey traveling and chronicling one of the world’s great trade routes, The Tea Horse Road. Jeff is the first westerner to have completed the entire route, stretching almost 6,000 kilometers through the Himalayas.

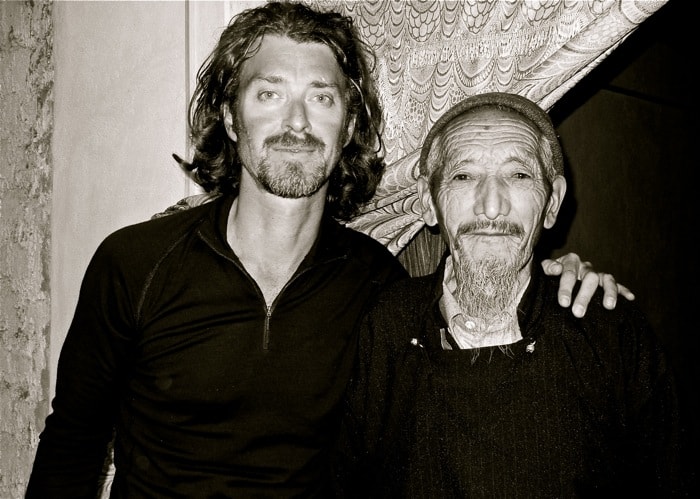

Jeff and Abdul, an elder from Ladakh. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

More recently, Jeff completed an expedition called The Route of Wind and Wool. This route traced one of the ancient world’s long lost trade routes, through some of the planet’s most daunting and stunning geographies – the desolate magnificence of the India Himalaya. The team was searching for the remains of the route – and the memories along it – in an odyssey by foot and mule through ice, over stone, and back into time on a 33-day journey by foot. It was the fourth such exploration in Fuchs’ series to revisit the lost Himalayan trade routes.

Landscapes in the mountains that render the mind numb. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

1. In this day an age, the idea of being an explorer seems like a romantic anachronism. Did you always want to be an explorer? How did you get started?

I grew up with a fair amount of moving, and with moving comes seeing and smelling, touching, and listening and expecting. I suppose there was always exploration in the blood without necessarily thinking that I was an ‘explorer’. Much time in my childhood was spent in the snow, and in the mountains and there was always the notion that there was all of this life, and all of these life stories to peak into that were ‘just over there’ beyond the ridge-lines. There was always an idea in me that one needed to live standing up, getting out there, and engaging. There was a time though when I realized that for me at least, it wasn’t simply enough to simply be stimulated and engaged; I wanted to be able to bring something back and to perhaps open up some of those worlds that I was fortunate enough to see, and feel. There is a kind of responsibility to exploration…and a kind of relentless hunger and persistence. Sometimes exploring bludgeons you, but it never leaves you alone.

2. You’ve done four expeditions in the Himalayas to revisit lost trade routes. Why the Himalayas? What’s the draw?

The Himalayas’ and their cultures, their huge spires and hints at ancient isolated worlds, really do take you into their folds without releasing. Years ago I was on an expedition (one of the first major Himalayan odysseys) cutting over a mountain pass at almost 6,000 metres and as I crested, I looked down into this snow-crusted valley and was struck to see a community of yak wool tents billowing in the winds. Apart from what I’d read, that moment and knowing that a culture was living on this very cusp of mother nature’s every mood hooked me to try and peer into how these people arrived and what kept them in such splendid isolation. A fascination I suppose with a community so isolated and autonomous appealed to so much of my being.

Since then I’ve focused on the trade routes that have passed, virtually unbeknownst to the west, through the mountains to open up the world of not simply trade, but DNA, linguistics, the environment, and a wider context of what makes the Himalayas such a vital crossroads. I’ve spent the last years living on the eastern extension of the Himalayas in Yunnan and simply being there one encounters, by extension from locals, other routes and fables. Part of my own root system has become entrenched in the region and with language and time, a region starts to become far more than simply a landscape of quick sensations; it becomes a place of entrenched feelings, facts, and memories. The Himalayas are now being regarded (as they should) as one of the globe’s most crucial zones for study, to fear for, and act upon, particularly given the whole global warming topic, so in some ways this region is a kind of vortex of magnificent life, culture, and risk, and it needs more attention.

Elders hold the memories of the great trade routes. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

3. How did you decide to do The Route of Wind and Wool? What inspired you to follow this route?

An old nomad first spoke of the route when I was researching another route, this one of salt. This wind and sun-scarred old warrior’s face and his words, remained in me for years until I heard from another source about this Route of Wind and Wool, which sort of confirmed the ancient’s’ words and urged me on. It had all of the ingredients if you will, of what I found so vital about the mountains themselves: a virtually unknown and misunderstood bastion (outside the regions it passed through), entirely local and time-honoured narratives, and a kind of history that wove people, climate, and products together in this big rainbow of life on the top of the world.

The wool in question, pashmina, has become almost iconic in the great market towns of the world that cater to luxury clothing, and yet this special wool (at its best) is sourced from rugged nomads who live in the most remote, high-altitude landscapes on the planet. Sourced and transported through terrain that tests the body and will like few others, the pashmina goats, and the wool they produce allow those very isolated communities to remain where they are, and how they are. It seemed a great, slightly risky quest, to open up a part of the globe that for many is simply a series of high peaks.

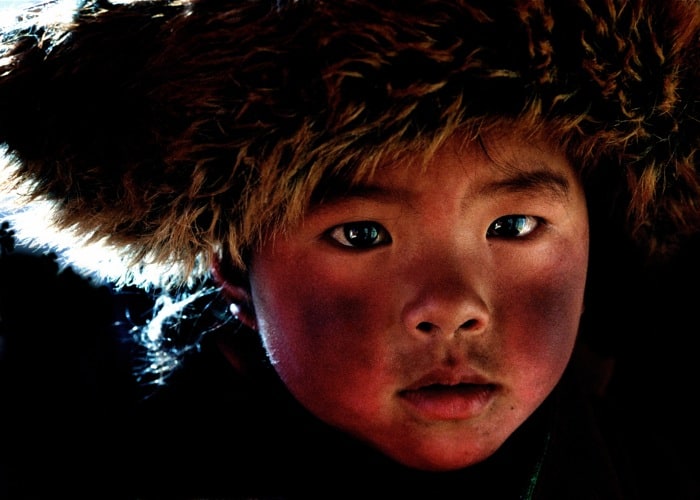

A young nomadic girl gives a fleeting glimpse of something timelessly mortal in Qinghai province. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

4. What did you discover on The Route of Wind and Wool? What experiences could other, perhaps slightly less intrepid travellers, enjoy along this route?

One thing that always affects me in the mountains generally is how these regions of daunting risk, utterly isolated lands, and barriers are in fact zones of protected micro-climates cultures, and safe channels. There are worlds within worlds that are seldom mentioned or referred to within the great snow peaks. The area we travelled through is basically long strips of mountain ranges through Ladakh and within the folds there are monasteries, and fertile valleys that prepare themselves for the winter onslaughts at which time the region shuts down entirely.

There is much that is utterly soft and humane amid such power. I think anyone is capable of wandering and enjoying the cultural elements along with the vast landscapes that are ruled by skies and winds. The market towns of old still hum and buzz with a dozen tongues, and they really still do have tints of their former selves. One only has to get away from the tourist veneer and peak behind it to see remnants of a past world that lives in the present.

5. What was the most difficult part of the expedition? How was the altitude? And what was the most rewarding?

What’s inevitably difficult for me about these expeditions is the return from them. Contrary to races to cross terrain in record time or summiting a peak in a couple of adrenaline fuelled days, these long expeditions of a month, two months, or longer, tend to grind a different way of seeing and processing into the being. Leaving these feelings and the giant spaces and elements feels at times like a stifling bag has been draped atop the body and mind. There are dips as the sensations and raw elements get knocked around by the speed sometimes necessary upon reentry into society.

I try to keep those mountain moments in a little mind-vault to be retrieved whenever possible and whenever needed. Altitude for me isn’t an issue and we only hit a mid 5,000 metre range — it is the length of time and the daily grinding that is what can take a toll. In terms of rewards, I simply marvel that a team (or solo) can still travel in relative autonomy, off-grid, and content for so long needing only each other and the sky for company and that vignettes of other worlds can remain so perfectly within our world of perpetual speed.

A nomadic matriarch (and our team’s hostess) in Central Tibet. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

6. Can you tell us something about the culture of the region you were travelling in? Is there a danger this culture will be eroded or diluted? What challenges are they facing, and can readers do anything?

Most of our expedition took place in Ladakh, which is a stunning land and a crucible of cultures of Central Asia, Tibet, and India. Pockets of nomads, trading peoples from Yarkhand, remnants of the great Muslim trading families, and from every point of a map, and a dozen cultures and languages all fuse together and yet remain distinct. All of this exists in a rich area of peace and diversity largely based upon where ancient trade routes bisected and funnelled into.

There are of course risks with every culture, no matter how insulated they might be that there will be an ebbing away of culture and of memory and that thing of the old world, oral narratives but the very altitudes and physical conditions sometimes act as a guardian against too much incursions. Much of the risks that affect the regions have to do with global warming and ever-quickening levels of glacier melt, so for better or worse there actually needs to be studies. I think travellers simply have to travel lightly — if that is even something we humans can do. People will never cease to physically travel, but perhaps we might tread a little more gently and spend time interacting with local cultures rather than racing through them on our

7. What advice would you give to someone who wants to be an explorer, or to travel adventurously in places like India, China, the Himalayas?

Be curious and relentless, take chances, and learn to look twice at everything … and never turn down a cup of tea!

A tea harvester plucks tea leaves from a tea tree in southern Yunnan province. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

8. You import teas from China. Why tea? What drew you to the “world’s most magical beverage?”

Though tea has been, in some form or another, in my life since I was young, it is only since I visited Taiwan’s world of ferocious and stunning Wulongs that I’ve been a happy and slightly neurotic dedicate of the leaf. [ED. NOTE: Nothing neurotic about it!] Beyond the fables, and the colourful ,historical aspects of tea, I was smitten with its stimulant, almost narcotic effects during a proper tasting high in Taiwan’s Nantou County almost 15 years ago. It is a fuel and medicine whose effects hit my own bloodstream with a rush of good and since then it has been the basis for much of my travel and seeking.

This interaction between a vegetal complex and us (humanity) is quite marvellous, and beyond simply the storied names and titles, and complex ceremonies, tea is still essentially something utterly simple for everyone. I recall sitting in one of the most famed of villages that produce Puerh’s (in southern Yunnan) in a tea harvesting family’s home on the floor and being served a tea that was that particular year’s most expensive and sought after tea. It was selling at ridiculously inflated prices in the tea towns and being fawned over as if it was a sacred item. The hostess of the family simply through the tea leaves into a pot that burbled on the floor. This was a tea that would have been snapped up at a few hundred dollars a kilogram, but was being casually slung about and served up with a wonderful kind of simplicity. It was a moment when tea (my version of it anyways) became clear in my mind. An utterly simple liquid gift of the earth that fuels, binds together, and cleanses … anytime and anywhere.

9. What’s next?

A lot more tea and another trade route later this year. The tea company model has slowly gained momentum: hand-sourced, limited quantity teas that rarely see much beyond the regions they’re grown in, served up in a monthly tea subscription. I don’t think the Himalayan trade routes (nor tea for that matter) will ever really ever be out of my system.

NOTE: You can join the tea club, and try a new tea every month, by visiting the Jalam Tea website.

Here atop the Lasermo Pass in Ladakh upon the Route of Wind and Wool. Photo courtesy Jeff Fuchs.

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.