Citywatch: Whether it’s action or traction in the food world, cities are stepping up to the plate. The world is fast going urban, as are challenges of social, economic and environmental well-being. Citywatch is crucial to Worldwatch. Wayne Roberts, retired manager of the world-renowned Toronto Food Policy Council, has his eye out for the future of food in the city. Click here to read more from Wayne.

Usually respected for its calm, cool and collected approach, the Canadian Urban Institute has been ringing the alarm for some time about the “giant demographic tsunami” about to roll over Canadian cities.

The scare tactic hasn’t worked yet in Toronto, where the mayor and his critics are locked in battle over yesterday’s programs and budgets, not tomorrow’s.

Mayor Ford, widely viewed as too stupid to know what’s going on, will win in the end if he diverts political attention from pro-active programs that prepare for the future, no matter how many skirmishes he loses in his bids to cut from the past.

Old hat as the issue may seem to some, the Canadian Urban Institute is trying to force that tiresome group, the baby boomers, into full frontal view once again—this time as the age group that has no place to go in a suburban metropolis made for people half their age and twice their physical resources and retirement income.

But what makes the Institute’s perspective relevant and “mainstreamable” to people of all ages is the way it recently intimated a possible new urban majority made up of minorities—seniors, children, teens, single moms, low-income workers, people on social assistance, newcomers, people with a range of physical, mental and psychological limitations, members of vulnerable groups, and the agencies and businesses catering to them—all of whom will benefit from a similar paradigm of urban redesign.

If these strange bedfellows mix it up right, people who share solutions in common, even though they don’t share similar problems or identical attributes, have the potential to rework tomorrow’s unique urban policy needs. Perhaps they can even teach old politicians new tricks and steer political discourse, framing and debate in a new direction.

Here’s how Institute reports present the issues. Early reports, such as Glenn Miller’s When we’re 64, cited the raw numbers of an aging population, and also showed how creaking bones of seniors would be matched by creaking infrastructure of cities as well as healthcare systems.

In 1961, when today’s cities were under construction, only one Canadian in 14 was over 65. In 2001, one Canadian in eight was over 65. Nine years from now, one Canadian in five will be over 65, and if nothing significant happens, they will be living in the same kind of city as was built in 1961—a city of mainly single family homes, without many mixed and walkable neighborhoods, with few main streets anchored by essential social and shopping services, and without rapid and convenient public transit offerings.

The bad news gets worse as the final bulge of the boom sets to retire three years later, and as the early boomers start to lose more of their strength, sight, hearing, health, friends, and personal savings, and become more dependent on the amenities of an urban commons which doesn’t exist.

The good news, which outshines the gloom, is featured in the Institute’s recently-released paper on “repositioning” the core ideas of “age-friendly communities” so they can be brought into the political mainstream. The June 2011 report is called Re-positioning Age Friendly Communities: Opportunities to Take AFC Mainstream.

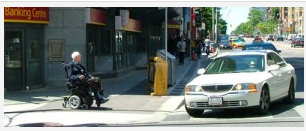

The case is put that making a building entrance senior-friendly isn’t much different from making it baby friendly—baby carriages and seniors’ walkers both do better on ramps than steps, and so do lots of other people, including travelers with luggage, shoppers with heavy bags, cyclists, people in wheelchairs, skiers who just broke a leg, and so on. The principle behind ramps is called “universal design,” as distinct from design that privileges a minority of young, able-bodied individuals who have no dependents, luggage, or bags to carry.

What’s good about ramps is also what’s good about scores of essential services. If they’re placed to be accessible by clients who come on foot, rather than placed in an austere high-rise convenient mainly for managers who want to supervise all their staff in one place, they serve the whole population, and reduce pollution from transportation.

Almost every service for every “minority” group can be universally designed to meet the needs of multiple user groups while also enhancing the physical environment and keeping costs under control.

The Institute report reviews all the “with it” standards for what’s best in cities—smart growth, active living communities, heat resilient communities, safe communities, healthy communities. Whatever the specific group or problem, there’s bound to be a school of planning that addresses their needs.

The genius of the Institute report is that it does the math, concludes that all these groups add up to a majority, and advocates an inclusive city designed to serve everyone equitably and efficiently through universal design. Instead of recommending the same old same old round holes that are no good for the majority of square pegs, there’s a malleable surface that supports all shapes and sizes.

Universal design is to design of appliances, buildings, and neighborhoods what employment equity is to the design of job competitions. Both achieve optimum efficiency and equity by removing all privileging based on arbitrary assumptions about what’s good and normal. As a consequence, everyone benefits and few, if any, are harmed.

Two things make universal design radical. First, it ends the competition among minority groups based on the obsolete notion that their needs require competition for scarce, mutually exclusive, resources. Second, it reconfigures the needs and rights of what have been called “minorities” as needs and rights of majorities, creating an opening for social and political alliances that can unify majorities behind positive reforms.

It may be that seniors will play a lead role in mobilizing such an alliance, if only because they have more time, enjoy considerable respect and prestige, feel valued, legitimate and are confident speaking out about their needs, and turn out to vote at levels that keeps politicians alert.

But this is a politics many can look forward to, if only political leaders start looking ahead.

By Wayne Roberts

Danielle Nierenberg, an expert on livestock and sustainability, currently serves as Project Director of State of World 2011 for the Worldwatch Institute, a Washington, DC-based environmental think tank. Her knowledge of factory farming and its global spread and sustainable agriculture has been cited widely in the New York Times Magazine, the International Herald Tribune, the Washington Post, and

other publications.

Danielle worked for two years as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Dominican Republic. She is currently traveling across Africa looking at innovations that are working to alleviate hunger and poverty and blogging everyday at Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the Planet. She has a regular column with the Mail & Guardian, the Kansas City Star, and the Huffington Post and her writing was been featured in newspapers across Africa including the Cape Town Argus, the Zambia Daily Mail, Coast Week (Kenya), and other African publications. She holds an M.S. in agriculture, food, and environment from Tufts University and a B.A. in environmental policy from Monmouth College.