In the English-speaking world, Annona muricata is called soursop. If that name is a turnoff, Spanish-speakers call it guanábana, French-speakers call it corossol or cachiman épineux, and the Thai know it as thu-rian-khack. These are just a few of the many ways to identify this distinctive-looking tropical fruit.

Native to Central America, northern South America, and the Antilles, soursop now grows wild and is cultivated in warm, tropical climates around the world at altitudes from zero to 1,000 feet above sea level. It has a nearly continuous season. The soursop tree grows between eight to 20 feet tall and is very sensitive to frost. Harvesters pick the oblong soursop fruit when it reaches a yellow-green color and full weight, between 10 to 15 pounds.

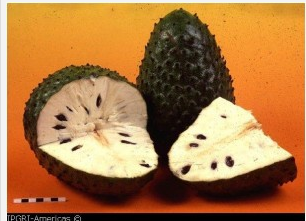

Mature fruits display a green or even brownish skin and are covered with small spiky protrusions. Soursop’s milky-white pulp is fibrous and punctuated with black, mildly toxic seeds. But if you make it through the spikes, fibers, and seeds to the heart of the fruit, your palate is in for a treat. Notes of sweet pineapple and strawberry, tart citrus, and smooth banana can all be detected in a taste that is singularly soursop. It’s a complex flavor to match its complex nomenclature.

Soursop isn’t known as a cash crop because individual trees produce a low yield of fruit. When you can get it fresh, the fruit is eaten raw with a spoon. Soursop also preserves well, so commercial farmers often squeeze it to make beverages, candies, custards, and jellies. Guanábana juice concentrate or carbonated soft drinks abound in Central and South American countries. Dominicans boil the flesh with sugar and milk to create desert custard. Indonesians cook the unripe soursop like a vegetable to be eaten straight or in soups.

Beyond the dining table, soursop is a respected ingredient in home remedies. Its black seeds, for example, contain oil that will irritate your eyes but ward off head lice, while the tree leaves have been used to deter bed bugs. Soursop juice and leaves are also used to mitigate ailments as diverse as dysentery, hematuria (blood in the urine), insomnia, eczema, and even drunkenness.

No matter where you are in the world or what you call this fruit, there’s no denying it has a look and taste of its own.

By Joseph Zaleski

Danielle Nierenberg, an expert on livestock and sustainability, currently serves as Project Director of State of World 2011 for the Worldwatch Institute, a Washington, DC-based environmental think tank. Her knowledge of factory farming and its global spread and sustainable agriculture has been cited widely in the New York Times Magazine, the International Herald Tribune, the Washington Post, and

other publications.

Danielle worked for two years as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Dominican Republic. She is currently traveling across Africa looking at innovations that are working to alleviate hunger and poverty and blogging everyday at Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the Planet. She has a regular column with the Mail & Guardian, the Kansas City Star, and the Huffington Post and her writing was been featured in newspapers across Africa including the Cape Town Argus, the Zambia Daily Mail, Coast Week (Kenya), and other African publications. She holds an M.S. in agriculture, food, and environment from Tufts University and a B.A. in environmental policy from Monmouth College.