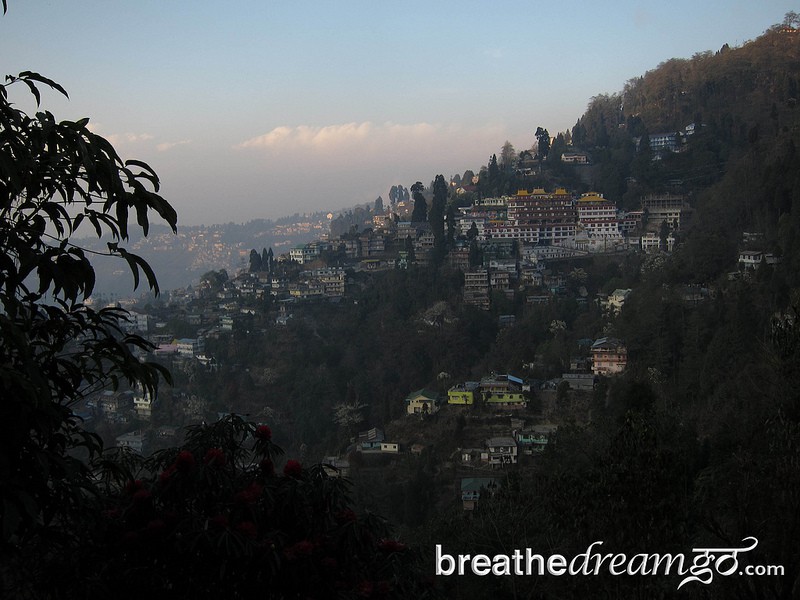

Darjeeling at dawn

Discovering the true nature of tea in Darjeeling

TEA HAS A MAGICAL effect. It instantly refreshes and soothes the soul. But, for me, it also carries an aroma of nostalgia — as if the past is steeped into the leaves, along with hope and optimism.

Is it the nature of tea leaves to impart this effect, I wondered, before I made my pilgrimage to Darjeeling? Or did I feel this way about tea because of tender memories of tea parties with my Nana when I was a child?

This is what I travelled to Darjeeling to find out. I wanted to ascend to the heights of one of the world’s great tea growing regions, the home of the “champagne of teas,” and to experience the spirit of tea first hand.

Tea gardens of Darjeeling

Tea with the Thunderbolt Rajah

I stand in anticipation before the row of white porcelain teacups. The King of Tea, Swaraj Kumar “Rajah” Banerjee – known in Darjeeling as the Thunderbolt Rajah – flourishes his arms as he speaks excitedly about silver tips, muscatel flavours, the movements of clouds and the secrets of growing the world’s most expensive tea. His quiet assistant, in an apron emblazoned with the green Makaibari logo, deftly pours a different tea into each cup, the colours ranging from pale straw to rich honey.

I am sampling some of the world’s finest teas – organically grown on the Makaibari tea estate in Darjeeling, land of the thunderbolt. Makaibari is the oldest tea estate in Darjeeling, the first to go organic and one of the most successful: they supply tea to the Tazo company, sold at Starbucks. As I hold the earthy, fragrant flavours in my mouth, I gaze out the window on the rolling green tea gardens, lit up by the late afternoon sun. I suddenly realize I am having the perfect Darjeeling moment: stimulating, refreshing and deeply satisfying.

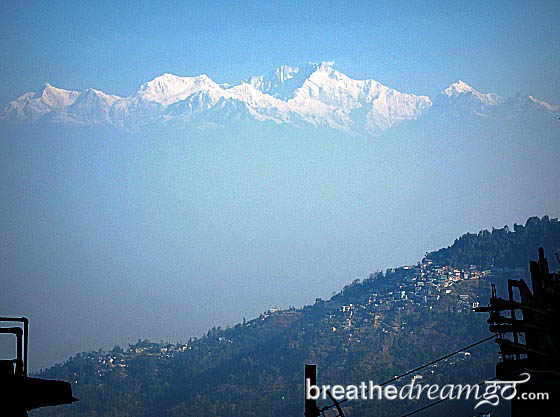

Mount Kangchenjunga presides over Darjeeling on a clear day

The scent of far-off lands

Though my grandmother, Nana, loved to bake and tell stories, there her resemblance to story-book grandmothers ends — for Nana was very elegant. She smoked with a tortoise shell holder, had long painted nails, wore Wallis Simpson-inspired A-line taupe dresses and drove a matching taupe-coloured car.

From the time I was about three years old, Nana and I had tea parties together. At first, she gave me a plastic tea set, and I remember drinking from the tiny cups. When I was about six or seven, she gave me a white-and-gold china tea set fit for a princess.

Nana lived with us when I was growing up. She had a way of making occasions special, and our tea parties are among my earliest childhood memories. We had tea together, just the two of us, in Nana’s small apartment, built onto the side of our house. She wore full make-up, ropes of thick costume jewelry around her neck and an enormous emerald-coloured glass ring, and served the tea on an antique table, on her last remaining Persian carpet. The tea was always accompanied by bread, honeybutter and stories.

Nana’s stories and the scent of tea – grown and harvested in a far-off land of mist-covered hills – transported me. Those tea parties were the first of many steps that eventually took me to India, and then, after an arduous journey from Delhi that included a bone rattling, four-hour drive up a steep road and into the clouds, to Darjeeling.

Tea on the terrace at the Windamere Hotel in Darjeeling

The story of tea

Darjeeling, the town, sidles precariously up a steep mountain face in remote northeast India. The region of Darjeeling spreads out for many miles in all directions beneath the town, and encompasses many tea plantations: tea cannot grow at the altitude of the town, it must be 1,000 metres lower.

The history of how tea came to India and the west is fraught with intrigue and adventure. It all starts in China in the 18th century when British traders began bringing crates of it back to England. The English acquired a taste for tea and soon demand far outstripped supply, and Britain began running a trade deficit with China.

British adventurers came up with the idea of growing tea on Indian soil, and began importing tea bushes from China into the regions of northeast India that had the most suitable growing conditions – namely, the hilly regions of Assam and Darjeeling. In fact, they discovered that tea grew indigenously in this region, and experimented with both the imported and natural varieties to achieve the best flavours and yields. As the British Raj flourished in India, so too did the tea trade.

During these wild east frontier days, Rajah Banerjee’s great-grandfather, G.C. Banerjee, escaped the confines of Calcutta to seek his fortune in the hills. He prospered at a very young age – by 20 he was already wealthy – and a friend bequeathed his estate to him. It was on this estate, Makaibari (which means corn field) that Darjeeling first’s tea plantation came into being, under the leadership of G.C.

Three generations later, when Rajah Banerjee was a graduate in England, intent on a future there, he went home to Darjeeling for a visit. While riding his horse among the tea plantations and forests of his ancestral home, he fell, and as he thudded to the ground had a life-altering, thunderbolt of an experience: “Beyond time and space, I saw a brilliant band of white light connecting me to the trees around me. The woods sang out melancholically in an incredible concerto, ‘Save us! Save us!’”

That was on August 21, 1970, and from that day to this, the “Thunderbolt Rajah” has put his heart and soul into saving the vanishing woodlands, and protecting and nurturing the people and culture of his Himalayan region.

Drinking tea in Darjeeling

I dutifully tried each of the teas that Rajah Banerjee laid out before me, and began to appreciate the subtle and distinct differences between them. “What champagne is to wine, Darjeeling is to tea,” he said. From light and golden, to rich and flowery, Darjeeling tea is delicate and delicious. The differences in colour and flavour are the result of many factors, such as the season it is harvested.

Over the course of an afternoon, Rajah explained the art and science of Darjeeling tea to me. “This is a magical, mystical land,” he said, “and the tea is symptomatic.” As a long-time student of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of biodynamic agriculture (precursor to organic farming), Rajah has been a tireless pioneer and advocate of human, cultural and environmental sustainability in Darjeeling. When he converted Makaibari in 1980, and had it certified in 1988, it became the first organic tea plantation in Darjeeling. Now, about 35% of the gardens are organic.

“Makaibari is an oasis,” he said. “We are not seeking to be a leader, but an inspiration. We have the tools here at Makaibari for a much better world, a sustainable world.”

For Rajah Banerjee, the end result is the flavour of the various teas Makaibari produces, such as their top-of-the-line Silver Tips Imperial, apparently the most expensive tea in the world — and my favourite of the ones I tasted (I bought a bag of it at the Makaibari store). But the process is equally important and it includes a long list of innovations in agriculture and in creating a sustainable human environment that protects the culture and the people who live and work on the estate.

Rajah teaches me to slurp, swish and spit the tea.

By the time we were finished talking, and drinking endless cups of white tea, served straight up, my head was spinning with the profound and deeply spiritual ideas of this caring, knowledgeable and charming man. “All problems of humanity are questions of harmony,” is a typical Rajah Banerjee statement, tossed off with a just-slightly-eccentric flourish.

I couldn’t wait to get out into the garden and experience the living tea plants for myself, and see if I could discern the harmony of Makaibari I had tasted in the cup. After getting some instruction on direction, I walked out into the garden closest to the office and factory — the large shed where the tea is dried, rolled, fermented, sorted, graded and packed.

I was in Darjeeling in March, almost in time for the “first flush” picking. The tea pickers, usually women, walk through gardens that resemble lush carpets picking just the top two leaves to make the finest teas. But when I was there, the tea leaves were not quite ready for harvesting, and when I walked through the Makaibari garden, I was alone.

As I walked along narrow tracks among the tea bushes, enjoying the scenery, I began to realize that I felt very peaceful, and not at all alone. In fact I had walked for quite a ways, and couldn’t see another soul. All I could see was an undulating tapestry of tea bushes, stands of forest, a ridge in the distance and the blue sky swept with the misty clouds that envelope this high altitude domain.

I stopped to look closely at the bushes, which came up to about my waist, to take in the tender top leaves glistening and bright in the afternoon light. I heard birds singing and took a deep breath of the fresh mountain air spiked with a green and earthy scent.

Everything we need is in this garden, I spontaneously thought.

Tempest in a tea pot

While writing this story, I braved a packed storage cupboard to unearth a box of half-forgotten treasures. Since my mother’s sudden death 15 years ago, I have recoiled from reminders of her, and Nana. I boxed up most of my mementos and pictures, and even banished some to my sister’s out-of-town attic. But I decided it was time to again hold the china teapot that my Nana gave me, and which I have carefully kept, sealed in bubble wrap, all these years.

As I held the familiar object in my hand, it was as if a piece of me returned from exile. Memories, and a bittersweet mixture of grief and longing for the past, washed over me. I could hear my Nana laughing, a light, quick laugh, and almost smell her spicy perfume, Shalimar. The happiness of those early tea parties, and the feeling of being surrounded by a loving family, resurfaced like a long-lost treasure. Such is the power of an object, even a child’s teapot, when it is infused with tea and love.

TEA LEAF GRADING

Most people are familiar with the orange pekoe designation, to denote tea, but probably have no idea what it means. Though there is no consensus on exactly how the term originated, we do know the word pekoe is derived from the Chinese word “pak-Ho” meaning “hair” or “down” (referring to the light white down on the bud leaves). In fact, grading tea leaves is a complicated affair, and is not consistent from country to country. Black teas are most extensively graded, followed by green teas.

Orange Pekoe (OP) is the most basic grade, and it describes the best, most tender leaves plucked from the tips of the plant’s young shoots.

Black tea is classified into four different categories (whole leaf, broken leaf, fannings and dust).

a

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.