On the ghats in Varanasi, India

Karma cola, karma chameleon, karma co-op, karma account, increase your good karma, it’s your karma baby…

Karma has become an all-purpose word in the west that is used fairly indiscriminately without much understanding of what it really means. This is probably a pretty common phenomenon when words migrate from another language / culture. I can tell you that, as a serious student of yoga, Hinduism and Indian culture, I have been trying to wrap my mind around the word karma for years, and I have barely gleaned its meaning.

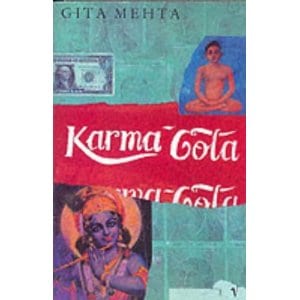

I’ve been thinking about karma for a couple of reasons lately. One, I just finished reading the book Karma Cola.

Karma Cola, written by Gita Mehta, was originally published in 1980. The author wrote it in response to the waves of hippies who washed up on India’s shores in the 60s and 70s, to avoid the American draft and the Vietnam War, to follow in the Beatles footsteps in Rishikesh, to find an alternative to the consumer-driven lifestyle of the west and to experience spiritual enlightenment — or at least spiritual understanding (which was — and is — largely absent in western culture, if you ask me).

It’s an entertaining book, full of colourful stories, and she certainly has her own pop-culture-influenced writing style (a bit dated now), but I found her thesis depressing and mean-spirited. The stories in the book describe encounters either she has had, or that she has heard about, between western spiritual seekers and Indian gurus. She seems to think that westerners who travel to India to pursue a spiritual path are gullible at best, and dangerously deluded — to the point of having a fragile grasp on reality — at worst. She shows no compassion for her subjects, no understanding of what might have compelled them to become seekers, and generally no sympathy for the human condition. The book is judgmental and holds to one viewpoint from one end to the other. According to Mehta, people are either idiots (westerners) or charlatans (Indians).

She makes one point that I agree with: it’s very hard for most western minds to understand eastern concepts — they are so fundamentally different. I have seen this phenomenon many times: western yoga students and travelers to India overlaying the western world view with yogic or Hindu ideas. It’s not easy to undergo the fundamental paradigm shift from the dualistic thinking of the west (founded on the notion that you only live once, and therefore must strive to achieve everything you can in this lifetime; and the right-or-wrong view of morality-based religion) to non-dualistic Hindu thinking (based on the notion of reincarnation, the vastness of time and the oneness of the universe).

And I am no exception. Here’s my understanding of karma.

Karma East and West

Karma means action. It is not a reward-and-punishment system; neither is it a cause-and-effect phenomenon. According to the Bhagavad Gita, which is the bible of Hinduism, Krishna instructs Arjuna that he must take his action — his karma — based on his duty — his dharma. He is a prince in the house of Pandava and therefore he must wage war against his cousins, the Kauravas, who are trying to usurp the kingdom. He cannot know or control the fruit of his actions; that is not his responsibility.

So Karma is, in a way, based on the actions we take, but not in the straightforward way we might think of it in the west. And your “karma” can be built up over lifetimes. So things happening to me now might be the result of past karma (past actions) taken in a previous lifetime.

I see the difference between east and west largely in the response to the idea of karma. Westerners think they can control karma, so it goads them into action: work out more, be nicer, get up earlier, pay bills on time, work harder, whatever. The ego mind of the westerner springs into action and tries to control the situation, to a desired outcome or effect.

I don’t see the same reaction in India. Indians tend to be more philosophical, more accepting, more resigned you could say. My teacher in India, Swami Brahmdev, would encourage us to increase our consciousness, in other words to learn from the situations we find ourselves in. Not to try and control or change the situations.

But I am still trying to learn this concept, so I am open to more insight — please comment!

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.