The early morning taxi to Nizamuddin train station, leaving behind friends, leaving behind Delhi and festival time, leaving behind Ajay. Last night we walked in the park at dusk with the sounds of Ravanna burning, and bursting in fireworks, all around us. Trees filled with unseen birds making a roof of noise. The Shiv Mandir in the park delicately lit, only Panditji inside, Ajay and he finally meeting after so many years.

THE MIRABAI EXPEDITION is a cultural journey to follow in the footsteps of Mirabai, a 16th century poet and Krishna devotee. I undertook the expedition in October 2014 by travelling to all of the primary sites associated with her in India.

I arrived at the station and was greeted by porter who demands way too much money, and I don’t have very much fight in me. He seems nicer than most, less hard, so I capitulate at an exorbitant 150 Rs, about two or three times what I should be paying. But he is going to wait with me for the train, find my car, my seat and put my bags on the rack. It’s very convenient and frankly worth the money.

We stand on the dirty, crowded platform and I watch children garbage pickers with bags slung over their backs, like small Santas, walking the tracks. They are all between 10 to 15 years old, very small, wearing torn and filthy clothes. A family sits on the ground in front of me, and the baby pees, leaving a puddle. The tiny mother, in a shiny bright yellow sari covered in glitter, lets him sit naked on the platform while she changes him.

I peel an orange and hand my porter a slice, which he accepts with a smile. He’s sitting on a stack of big sacks filled with something like rice.

On October 2, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched a nation-wide Clean India campaign on the birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. The campaign makes me notice how dirty India is like never before. There is garbage everywhere, wrappers, bottles, plastic bags, and open sewers, animal shit, red streaks of pan spittle. India is impoverished, but does it need to be so dirty? Can people change? Just as I am wondering this, a middle class man drops a wrapper on the platform about a metre from a dustbin.

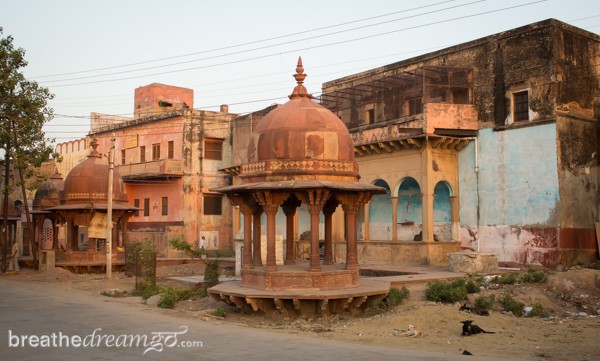

The Parikrama Road in Vrindavan.

The train arrives on time and I find my seat, beside a large and assertive couple. I sense they would like to spread out and take all three seats and I feel I have to fight for my space as first her elbow, and then his (after they change seats) appears in front of my face.

I try to read my book about Mirabai but it’s hard to concentrate on the flowery language, full of descriptions about her devotional fervour. I don’t feel this kind of spiritual intensity so it’s hard to imagine or grasp. Is belief an act of faith? Is it a feeling, like falling in love?

As I set out on my Mirabai Expedition to trace her route, her journeys and try and get a sense of her life, I wonder how similar we are, and how different. I was born into a kind of freedom she could never have imagined as a woman in traditional India. But I cannot imagine her religious fervour, and her courage in striking out on her own to travel the dusty roads of India.

The train ride from Delhi to Mathura Junction is only two hours, and it arrives pretty much on time. I’m hungry as I have only munched on some fruit, an Indian milk drink and a cup of railway chai — which comes in a small cup, with milk, sugar and tea bag for 7 Rs. I forgot to pack my thermos.

Rooftops of Vrindavan, a sacred city filled with temples devoted to Krishna.

The Taj Express stops in Mathura only for three minutes, and a large group has piled up their suitcases in the door. They notice my concern and make way for me to move to the next door. After I get down, I notice someone has been calling me on the phone, and before I can answer, a smiling young man says my name — actually a word that sounds “enough” like Mariellen for me to know it’s Pupendra, the person I am supposed to meet. He takes my bags and we walk a long distance down the train platform to the car park, where masses of green-and-yellow autorickshaws are waiting.

I notice they are larger than their Delhi counterparts, and many are decorated with leather applique of large flowers. I wonder if this is a good sign. Pupendra tells me Vrindavan is “a special place, best place in India, most sacred city.” Then he hands me over to his friend, whose name sounds like Sagar, and whose auto is perhaps somewhat less “smart” than the others. Sagar is going to take me to Gopinath Bhavan in Vrindavan, where I’m staying.

It’s a long, hot, dusty bumpy ride — first out of Mathura and then through a stretch of country side and into Vrindavan, which does seem a bit different than your typical Indian town. We drive down narrow cobbled streets, and everything is dry and dusty and a kind of pale ochre colour that reminds me of Italian Renaissance paintings.

The facade of Gopinath Bhavan, ladies ashram in Vrindavan.

Finally, the river Yamuna appears on our left and we drive along a narrow road with a line of intricately carved temples and ashrams on the right, facing the water. Some of the buildings are quite lovely, with cupolas and spires and carved facades. We stop at one of the loveliest, a large three-story building made of deep rose sandstone and carved in traditional haveli style. This is Gopinath Bhavan, a ladies ashram in Vrindavan that looks old but is actually quite a new building. Out front, cows are gathering to drink, I see monkeys above in the single tree, and groups of devotees walking, barefoot.

Inside, the courtyard is cooler and rosy-hued, with some plants and flowers hanging down from the balconies. I am met by Tungavidya Dasi, who I only know from Facebook, and she signs me in and shows me my room. I’m very happy to meet her in person, she is a warm and sweet-faced Dutch woman with white hair in a pale sari.

I’m on the top floor with a view of the river and the Parikrama Road — the road the devotees walk along as they do their circle of the town. The room is really a small apartment with some Indian furniture and an Indian-style kitchen and bathroom. It has a screened-in balcony — the whole place is monkey proof — and reasonably comfortable, but it needs a good cleaning. Tungavidya kindly arranges the cleaning and supplies me with sheets and a towel while I go out to find the ISKCON Temple and eat lunch at Govinda’s restaurant.

The ISKCON Temple in Vrindavan.

At Govinda’s, I eat a big vegetarian lunch, in the company of a Russian woman who looks, with her round face and head scarf, like a stereotypical Russian peasant woman. She tells me she’s been coming here for 25 years, and she explains the food I am eating is not Indian, it’s Vedic. The waiter has fixed up to bring me a thali, though it’s not on the menu. I get a little of everything, and it’s very good, followed by their signature herbal tea, a rich and satisfying drink.

Though having seen only a bit of the town and not really experiencing it — especially not the spiritual side of Vrindavan — I am wondering what the attraction is. The auto drivers, the usual touts, and others who work in these kinds of tourist and pilgrim centres all seem alike, and Vrindavan is no exception. They try and get as much money as they can from you, they happily give you misinformation and they seem, for the most part, apathetic.

After failing to buy an umbrella and finding only empty ATMs, I go back to the ashram with almonds, water and Limca, very happy to see my room cleaned, and I promptly fall sound asleep. Which seems like the sensible thing to do between 2 and 4 pm, when the sun is baking hot.

At 5 pm, the scene outside my window seems milder, the long slanting rays adding a picturesque quality to the Indian version of Canterbury Tales. It’s time for me to find the Mirabai Temple, so I grab my camera bag, make sure I am monkey proof and headed out into the melee.

The half-hidden sign for the Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan.

Walking in the heat and dust, avoiding the cows, cow shit, pilgrims, monkeys, bicycles and autos, trying to keep ahead of the touts and finding people who could point me in the direction of the Mirabai Temple is quite trying. The narrow river and few dusty trees supply very little respite.

After walking for about 15 minutes and asking many people, I find myself in a narrow, ancient street. A sewage drain runs down the side of the cobbled lane, brick shows through the crumbling ochre-tinged plaster, scalloped door frames surround heavy, wood doors, and again I am reminded of medieval Europe — except with monkeys and eastern architecture. Finally, a small sign, and a door to an even narrower lane. Another false start, another tribe of menacing monkeys, and I find it.

Through a rusty gate and I’m in a small, cool, serene, blue-and-white courtyard. Charming, fresh and modest, the Mirabai Temple is more like a home. A small group of Indian pilgrims sit in front of a grate where a white bearded man is talking to them. They are all very engaged. Unfortunately, it’s Hindi and I understand only a fraction. However, the bearded man speaks English and agrees to repeat what he’s said.

The Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan is not well-marked, not easy to find.

He explains that his ancestor built this home for Mirabai, five centuries ago, and she lived here in this spot for 15 years, before going to Dwarka. I am absolutely delighted to find such a charming spot and such an articulate, open and fascinating man. I can’t believe that I have been so lucky on the very first day of my pilgrimage expedition.

Praduman Pratapsingh of the Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan.

I take photos and a short video and realize I have not brought a notebook. I tell the man I will be back tomorrow to interview him and I leave at sunset. As I walk back along the busy road, I take a detour along the river bank, avoiding the monkeys but putting myself in the way of the river boat touts. It’s worth it to take some stunning photos of the huge orange ball of the sun sinking into the river, and the colourful small boats gliding along the surface. A boy rides a huge black water buffalo across the river and as I take a video they suddenly emerge right in my path and I run.

Everywhere, there are animals and people in this dry landscape. A manic, naked holy man suddenly appears and runs down to the boats. He is wearing only a Brahmin’s thread. He doesn’t surprise me at all.

I pick my way carefully back to the ashram and dive into the quiet and safety of my room — which luckily, and surprisingly, has an A/C unit — to think about my day.

I realize that I desperately need a sanctuary to be in India, I can only expose myself to the heat and the crowds and the challenges and the noise for so long. It’s hard on my nerves, and it’s also emotionally draining.

Sunset on the Yamuna River in Vrindavan.

During lunch at Govinda’s, I listened to the Russian woman talk about Vrindavan, and the mythical lore of this place — where Krishna and his gopis cavorted on the river bank — with bemusement. The classical image of pastoral, lush and harmonious Vrindavan are so far removed from the dirty, polluted, over-crowded, dry, monkey-menaced, scorched-earth reality of today that it’s shocking.

I read that Mirabai was also shocked when she arrived in Vrindavan in the mid 17-th century because she didn’t expect any buildings. She too was expecting a pastoral paradise. Is this what faith is all about? That we hold up an ideal to hang onto in the face of the disappointments of reality?

Anyway, I’m here, and I’m lonely, and I don’t love Vrindavan, I don’t feel I have found a sanctuary, and I’m not sure what I’m doing here. Except dedicating myself to the discipline of the pilgrimage, to stick with it, and go through whatever ups-and-downs, emotional roller coasters and life lessons are in store for me. Perhaps this is my first glimpse into what it may have been like for Mirabai — to leave the comfort and safety of home to follow her heart and the call of her soul.

Top photo: Praduman Pratapsingh is the 9th generation in his family to live in the Mirabai Temple in Vrindavan. The trip was made possible by an Explorer’s Grant from Kensington Tours, as part of the Explorers-in-Residence program.

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.