I didn’t ride a horse into the crater of Mount Bromo—and nobody should.

I have a fascination with deserts. I enjoy their being completely wild, the fact that they make me feel only a tiny part of this huge universe and that they test my limits. I never tire of staring at mile after mile of sand dunes, rock formations and dry landscapes against a clear sky. I laugh whenever I have to dust off the sand, when it takes two or even three showers to get rid of the residue I have in my hair.

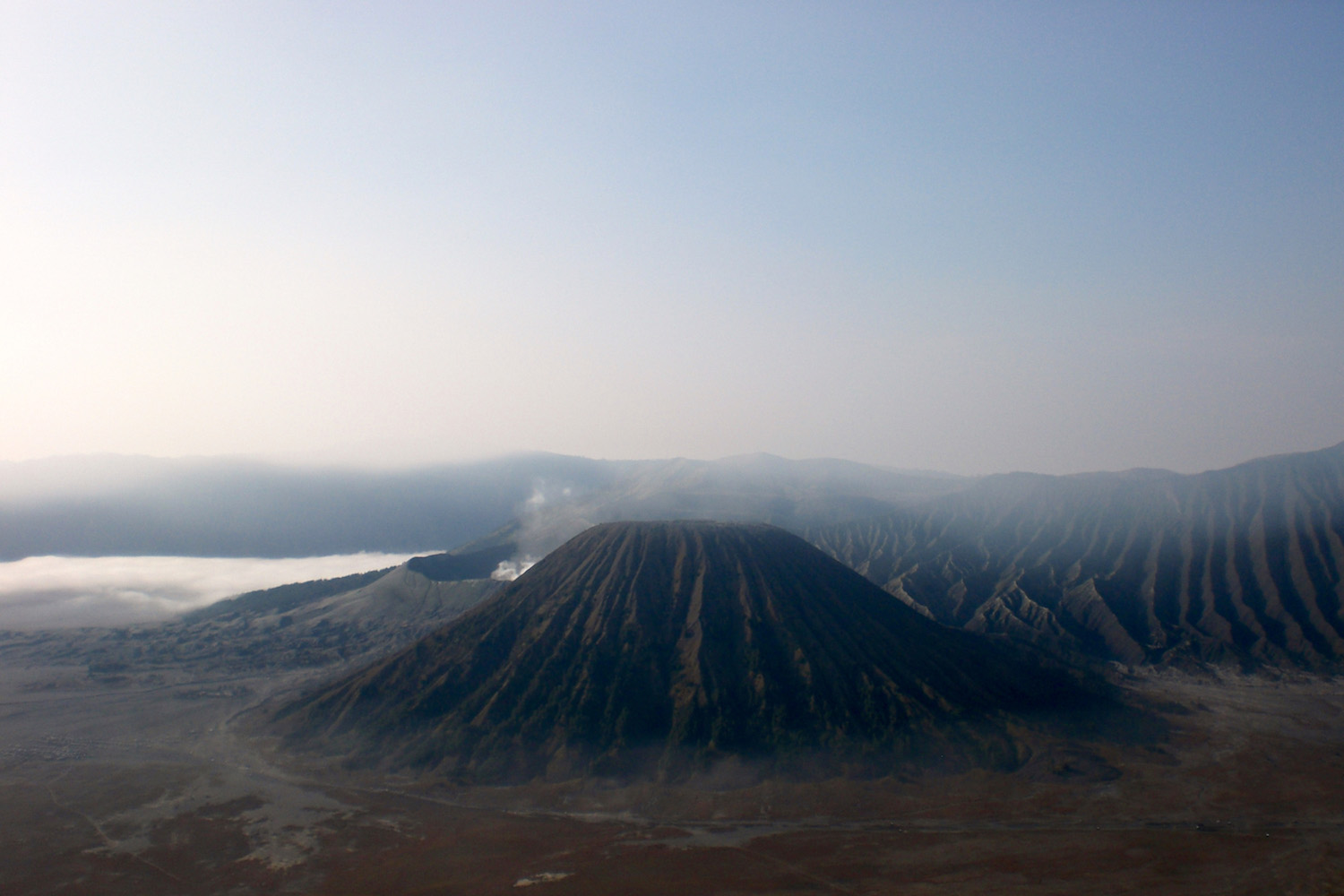

Put together my fascination for deserts, my obsession for volcanoes, and the fact that I love animals, and it is easy to imagine why I felt thrilled at the thought of crossing the Sea of Sand to Mount Bromo, a volcano which is one of Indonesia’s iconic attractions, and to ride a horse into its the crater. This may well qualify as a once-in-a-lifetime experience, I thought.

Being the optimistic person that I am, I decided not to be bothered by the hordes of jeeps and motorbikes that made their way through the desert, speeding as if racing for a prize, disregarding basic safety rules (up to 3 persons were riding on each motorbike, not wearing helmets, skidding and, not surprisingly, falling as a consequence) and raising big clouds of dust—as if breathing through the sand wasn’t difficult enough already.

By the look of it, I was not in for a solitary ride through the desert. But by then, I understood that in a country as crowded as Indonesia there isn’t much of a chance to get away from people. Besides, I have never really been bothered by large crowds of tourists—they generally don’t distract me from the beauty of an attraction. I didn’t let it bother me in crowded Bali, where it was just me and the amazing sunsets, I wasn’t going to let it bother me here, I told myself.

Looking forward to my ride, I began questioning the guides about the state of the horses we’d be riding, concerned about their treatment. The answers I got were quite vague and elusive. I wondered if it had to do with poor communication (“Perhaps my English is too difficult to understand, my accent too strong?” I wondered), or if this should raise an alarm in my head to what was coming next. Once again, I preferred to be optimistic.

But when I saw the horses available for a ride, I realized that they looked starved—ribs-sticking-out-of-their-ribcages starved. They had evident signs of distress such as persistent stomping and foam at their mouths, and kept chewing on their bridles. They looked too thin and unfit to carry a person, let alone the significantly overweight Western tourists I saw around me.

It took me only a split second to decide that there was no way I would ride the horse I had been assigned and a good discussion with the guides to explain why I wouldn’t. They were evidently shocked by my reaction—I guess they had not considered that anybody would show any interest for the welfare of the animals.

I ended up walking to the crater. It was completely doable, to the point that I don’t even understand why horses should be used in the first place—but I do understand that, done under the right conditions, this would have been a fantastic experience, very appealing to a lot of tourists.

I could take the sun, I could take the dust that I kept breathing despite the mask I wore over my mouth and nose. The only thing that bothered me as I hiked up (and coughed up) to the crater was the immense crowd of people that showed total disregard for the horses who struggled to get to the top and whose only interest was taking the ultimate selfie while they stared down that crater as the sulphuric gas came out of it, producing a big cloud of stinky smoke.

That wasn’t my idea of a ride.

Taking responsibility for our actions

Animal welfare isn’t exactly a national priority in Indonesia—in the sense that the majority of people don’t really bother with it there. It may be due to poverty, it may be due to ignorance and even to cultural differences. Yet, I do care about animals and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t bothered by what I saw on Mount Bromo. Besides, I’ve never appreciated using culture as an alibi for cruelty (against either human beings or animals). I would be disowning myself if I didn’t protest in the face of what I saw.

I can somehow accept that the locals wouldn’t understand my worrying for the horses. There is one thing, though, that I can’t accept. I can’t tolerate the fact that, despite knowing better than doing that, the vast majority of Western tourists rode those sick looking horses anyway. Would have they done the same back home? I doubt it. They would have most likely been infuriated at the conditions in which those animals were kept. They would have complained.

And this is when the cultural relativistic argument becomes useless; when wanting to overly justify and explain at all costs what simply is a bad behaviour isn’t doing any good to a country and isn’t going to improve things for its people.

We all want to have a good time, even more so when we travel. I surely do. We all want to be amazed by what we see, but it doesn’t always happen and traveling can be frustrating and even stressful at times. We all want to share our fantastic experiences and make others jealous for what we are able to do and see—we are humans after all. Yet, it is important to also share our misadventures and to say what bothers us, what we don’t like about a place and why.

Travel does create bridges, and I do believe that it has the potential to improve the lives of people. That is why I think that, even as travelers, we have the duty to take responsibility for our actions. Change will only happen when we will all change the way we behave. If we want to talk about responsible tourism, we first need to become responsible tourists.

This is what I understood when tears of anger and frustration rolled down my cheeks on that awful Sunday on Mount Bromo, in Indonesia.

Robert Schrader is a travel writer and photographer who’s been roaming the world independently since 2005, writing for publications such as “CNNGo” and “Shanghaiist” along the way. His blog, Leave Your Daily Hell, provides a mix of travel advice, destination guides and personal essays covering the more esoteric aspects of life as a traveler.