Immersing in the spirit of Algoma

Last week I travelled back in time, both to a primordial world of ancient rock and brooding wilderness; and to a much earlier time in my own life, when I was a teenager and wanted to be a painter. Back then, I was fascinated by several Canadian painters, including the artists who comprised the Group of Seven. I recently went to Algoma Ontario, a rugged region of natural beauty that inspired the Group of Seven to create a new style of art — one that was suited to capturing the spirit of the Canadian landscape. They originally journeyed there in 1918; I made the trip almost 100 years later! This is what I found.

Algoma is: Cold turbulent water, big sky, craggy coastline studded with weathered and bent pine trees and overhanging all the intense, brooding spirit of this vast wilderness. The Canadian landscape in north Ontario around Lake Superior is uniquely rugged. The weather is extreme, Lake Superior is a mighty sea, the bedrock of the Canadian Shield is ancient and the local Ojibway stories are entrancing. Combined, they give this area, Algoma, a very special feeling. There’s a power inherent in the immense wilderness that is palpable here.

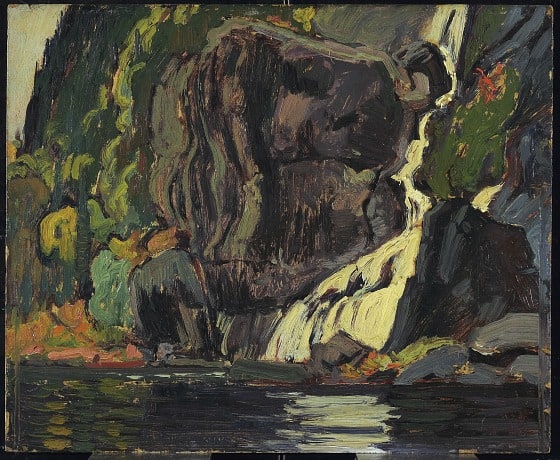

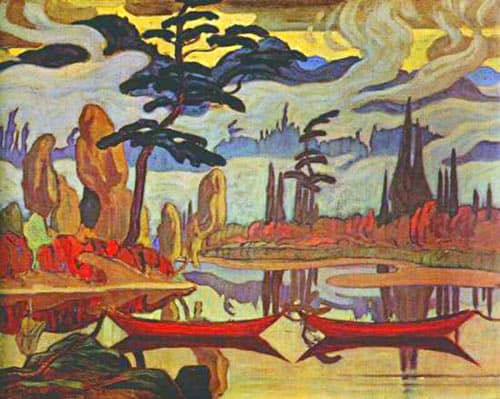

It was this landscape, with its jagged rocks, rich colours and powerful spirit that captured the imaginations of the the artists who would become known as the Group of Seven. This landscape demanded a new visual representation, a new language of art. Canada doesn’t look like Europe, so European traditional painting just doesn’t do it justice.

From 1918 to 1922, the Group of Seven artists, starting with Lawren Harris, the “spiritual one,” made numerous sketching trips to Algoma. Harris bought and outfitted a box car, which he had pulled into places such as the Agawa Canyon; and it was from this boxcar they made their forays into the wilderness.

While I was hiking in Lake Superior Provincial Park, I heard a woman who was admiring the view of the coastline exclaim, “It looks like a Group of Seven painting!”

The result was revolutionary. The painting style they created has become iconic, and is deeply etched into the Canadian psyche. So much so that someone can see this landscape and reference the Group of Seven images as archetypal, as if the paintings came before the lanscape itself.

As a former art student I too, was drawn to the Algoma region of north Ontario (about an eight-hour drive straight north from Toronto) to see the sites and landscapes that gave birth to this new school of art. I was not disappointed. My four-day trip to Sault Ste. Marie, Agawa Canyon and Lake Superior impressed me with unending natural beauty. But mostly, it was the spirit of the place that struck me. I felt it when I saw how crystal clear and aquamarine the water is; how sweet the air smells; how vast the landscape is, dominating the thin strip of human civilization that runs around the perimeter of the lake.

One day I hiked several kilometres up to a lookout that marks the spot, far in the distance, where the steamship Edmund Fitzgerald sank in 1975. This tragic event was commemorated in a haunting ballad by Canadian singer/songwriter Gordon Lightfoot — another iconic Canadian creation. On the way back through the green, dark forest I kept feeling a presence, but whenever I looked, I saw only a crooked tree or a churlish stump. I had to pee, so announced this to the forest, as a bit of an apology, thinking I didn’t have any toilet paper or water, and suddenly a big leaf flew in front of me and landed on the ground at my feet. It was a calm day, no wind, and on the entire three-hour hike, I never saw another leaf fall.

I also felt the presence when I saw a small group of Native people walking around the lake with feather-and-bead adorned walking sticks in hand. I kept seeing them, whenever I went out driving, and debated stopping to talk to them and perhaps take a photo. But something stopped me. I didn’t want to intrude. One man in particular, tall and well-built, walking with determination and purpose, really impressed me. I got goosebumps when I saw him. I’m not sure why they were walking around the lake; I asked around but no one really knew. They thought perhaps it was to draw attention to the lake in an effort to keep it clean.

I felt it when I was deep in the Agawa Canyon, at Agawa Canyon Park, a sumptuous natural paradise of thick trees, soaring rock cliff faces and a tannin-rich, placid river. And, perhaps more than anywhere, else I felt it when I was on the narrow rock ledge of the Agawa Rock in Lake Superior Provincial Park, staring at the ancient Native pictographs of sea creatures, voyages and Mishipashoo, the lynx-like spirit of the lake. I sat on the rock ledge, on a calm day, with the startling clear aquamarine water lapping at my feet, thinking about Mishipashoo; thinking of the people who had been lost to the mighty lake — some swept right off this ridge of rock on gusty days — and felt the power of the place. It was subtle and intense; I felt completed surrounded by living, breathing nature, immersed in the spirit, and at one with all of it.

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.