It’s make or break time for Venice tourism, unless it’s already too late. At peril is everything that makes Venice a place of “outstanding universal value,” Unesco’s criterion for a World Heritage Site. See Venice now, before it earns a place on Unesco’s endangered list.

Although Venice has been fighting back the sea for centuries, time is not on its side. Unesco has warned the Italian government that the floating city must immediately prohibit passage to the largest ships and tankers. Looming deadlines keep getting pushed back while a raging debate heats up, as it has done for more than five years.

A rainstorm approaches as water from Grand Canal floods the pavement at Hotel Danieli entrance

During the long rainy season, in Piazza San Marco they no longer remove the tables in between floods. They’re kept handy stacked up against buildings, ready to be erected so people can navigate the famous square, the lowest point in the city.

Skies turn blue following another midday flood in Venice, St. Marks Square

Venice Versus the Adriatic

It’s been more than half a century since the catastrophic floodwaters of November 1966 reached nearly 6.5 feet. In some hotels, longtime employees can point to a permanent water mark left on the wall. Yet it seems treasures were lost in vain; stakeholders, government officials, environmentalists, historians, and the cruise industry still have no shared vision nor coordinated strategy for saving Venice.

A rainy autumn morning floods Venice for several hours

Some will point to the delayed 2018 completion of Mose, a massive 15-year experimental 78-gate flood barrier project designed to fight the laws of nature. Others explain that ancient buildings supported by millions of wooden pilings, with their waterproof membranes in aging brick foundations already penetrated, are simply no match for erosion, global warming and rising sea levels.

Mostly, residents are alarmed.

Photographers capture images of floods at San Marco, the city’s lowest point

A Crush of Cruise Ships

Every year, 650 ships pass through Giudecca Canal, including the world’s largest cruise ships resembling floating skyscrapers, measuring as long as the Empire State Building is high. These vessels displace enormous amounts of water as they motor through the canal, damaging the lagoon ecosystem and the fragile brick and wood foundations upon which the city is built.

Gondolas bob as a cruise ship passes through the heart of Venice, Italy (photo: Creative Commons)

They resemble modern day sea monsters, dwarfing Venice’s delicate 15th century architectural masterpieces, forcing waves ashore to lap the pavement flooding alleyways, shops, restaurants, piazzas, and church interiors.

Thigh high waters begin to recede in Piazza San Marco

These floating hotels dump hordes of (already fed) tourists into over-crowded tiny Venice streets, who return to their dinner and a bed onboard. Only half of Venice’s estimated 25 million annual visitors check into a hotel, driving average room rates down, while uplift in demand encourages developers to add more and more rooms to the existing inventory.

When Venice Resembles a Theme Park

In summer months, when 60,000 visitors a day outnumber locals by 20-to-1, debates ensue over balancing Venice’s priceless charm against its Disneyland-style hordes.

In 2014, a solution to ban vessels over 96,000 gross tons from the landmark canal and to implement docking along another channel was overturned within three short months for fear of lost revenues. The debate is heating up. Meanwhile, construction continues on nearly 50 modern and technologically advanced cruise ships, most of which exceed that tonnage limit, all eager to place Venice on their itineraries by 2021.

A screenshot from TV news shows enormous cruise ship entering the Giudecca Canal in Venice

Venice Tourism: A Double-Edged Sword

Venice desperately needs tourism to survive. Yet the city’s very existence is under threat due to the crush of tourists it attracts. The relationship between tourist numbers and the rapidly shrinking resident population — currently at a new low of 54,500 (down from 120,000 in 1980) — is completely out of whack and not sustainable.

Our Venice tour guide explains why she has had to move out of town

In the height of summer season 2017, thousands of Venetians campaigned against the huge numbers of tourists “overtaking” their city. Last year, Venetians took to the water in boats and wetsuits, demonstrating their passion in trying to block the passage of the cruise ships.

While politicians wrangle, locals weighed in on a referendum with a landslide 98.2 percent hoping to ban cruise ships from the lagoon and to stop the excavation of new canals for big ships.

Meantime, residents see the price of housing in the historic center go spiraling out of control as apartment buildings are converted into profitable hotels and short-term rentals. Even the gondoliers, one of the best paid jobs in town, must live on a neighboring island to avoid Venice’s sky-high prices for everyday foodstuffs and basic items, all of which must be imported and transferred by sea.

Venice is Drowning

These days, an average winter season sees more than 100 days when Piazza San Marco floods and plastic galoshes are sold next to Prada and Gucci Swarovski-studded high heels.

Stilettos sparkle in Venice shop window while tourists buy 10 euro galoshes

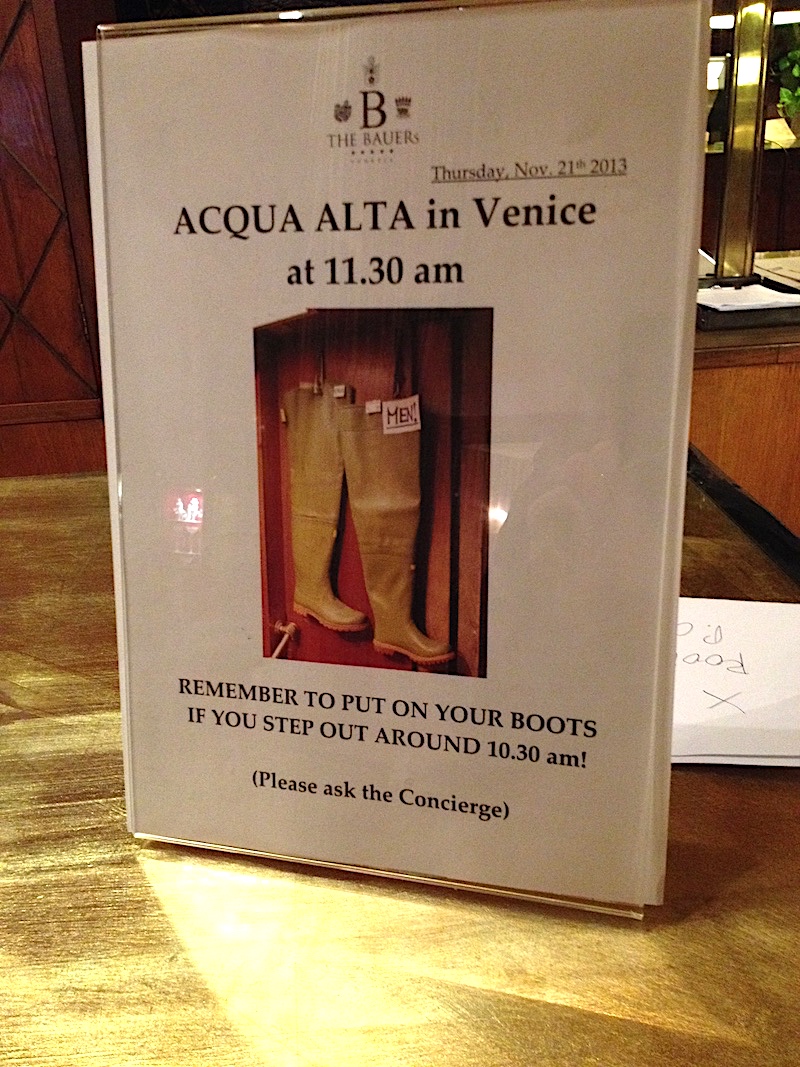

On a November morning, hotel reception placed a discreet sign, “Acqua Alta,” illustrated with a pair of knee-high boots. The well-informed knew that by mid-morning, Piazza San Marco would resemble a swimming pool and the sprawling maze of rising water in Venetian passages would render much of the central tourist district unnavigable.

Good morning, it’s a flood day in Venice!

By early afternoon, the water would recede, leaving shopkeepers once again managing sand bags, mops and garden hoses to draw sea water back out into the lagoon.

“Heads down!” Boats can barely squeeze under the arch of Venetian bridges on flood days, even as skies turn blue.

Hours after the flood, our boat barely squeezes under a Venetian bridge

Venetian Flood Alerts

Acqua Alta, defined as about three feet above normal high tide, occurs between late September and April when certain events coincide:

- Very high tides, usually during a full or new moon

- Low atmospheric pressure

- A scirocco wind blowing across the Adriatic Sea

Depending upon the season, on your next trip to Venice consider taking knee-high waterproof boots. If you forget, be assured that there’s fast trade by street vendors in bright yellow galoshes on sale at an inflated price.

Venice dries out

Wondering how deep the water will get? Listen for the city-wide warning siren followed by the beeps on a digital sound system in place for the past 10 years. The number of beeps indicates the expected level of the next high waters washing over this city of 400 bridges, with an “exceptional high” when flood water exceeds 140cm (more than 4.5 feet) above standard sea level.

Here’s a clue: the beeps you hear in this pedestrians-only city are not car horns and four beeps is not good news. You’d head for higher ground…if there were any.

A career-long tourism, destination, hotel sales and marketing pro, Laurie Jo Miller Farr is a dedicated urbanite who loves walkable cities and has a knack for always finding the best public restrooms. As a San Francisco-based travel and copywriter, she enjoys views from its crazy signature hills following half-a-lifetime promoting her dual hometowns, a couple of oh-so-flat places: NYC and London. Her work is found online at USA Today, Yahoo, Eater, CBS, Where Traveler, and more. She tweets @ReferencePlease and posts on Instagram @lauriejmfarr.