![]()

![]()

Spotted deer at Ranthambhore National Park and tiger reserve, Rajasthan, India

My first night at The Farm Villa, near Ranthambhore National Park and tiger reserve, I pointed out the constellation Orion to owner-manager Satish Jain. The hunter was highly visible in the night sky over rural India, his belt of stars particularly bright. I told Satish that my father, Douglas, taught me about that constellation and I have associated it with him ever since — and especially since his death seven years ago.

The next night I walked out onto the rooftop terrace of The Farm Villa and, though the night was clear, Orion was nowhere to be seen. There was a hole in the sky, a hole that mirrors the hole in my heart, where I am missing my father. Likewise, there is a hole in Ranthambhore since the March 1, 2011 death of legendary tiger protector Fateh Singh Rathore. And there is a hole in the effort to save India’s tigers from extinction. Though the 2010 census figures show an increase in the tiger population in India from 1,411 to 1,706 over the past four years, the habitat — and especially the all-important corridors — have decreased significantly. Tigers need a lot of land to hunt, roam, and mate, and without it, it is unlikely they will be able to survive and thrive in India. For an excellent article that captures the complexities and challenges of the situation facing India’s tigers, I recommend reading The failing fight to save India’s tigers by Stephanie Nolen of the Globe and Mail. For the rest of my story about visiting Ranthambhore, read on.

Ranthambhore National Park and tiger reserve, Rajasthan, India

I had longed to go to Ranthambhore park for many years — to meet Fateh Singh Rathore and, of course, spot a tiger in the wild. I finally went at the end of March 2011, just a few weeks after Mr. Rathore’s death. It is impossible to over-estimate what this man has done for Ranthambhore, for the Indian tiger and for all the other species of flora and fauna, as well as the human community, in and around Ranthambhore in southern Rajasthan.

The desk of Fateh Singh Rathore, Tiger Watch Office

Mr. Rathore’s presence is palpable at the Tiger Watch office, an organization he founded and housed at the back of his home in Sawai Madhopur. His photograph is propped up on his chair and his desk undisturbed since his March 1 death from lung cancer. I met Dr. Dharmendra Khandal, a conservation biologist and passionate champion for the ecological diversity of Ranthambhore, at Tiger Watch, and he showed me a slide show, called A vision of greater Ranthambhore, about the organization’s efforts to stop poaching, rehabilitate poachers and their familes and offer a strategy for tiger conservation.

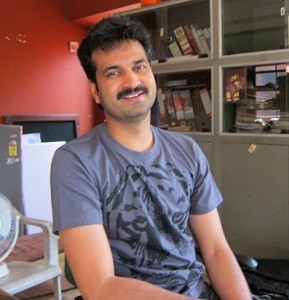

Dr. Dharmendra Khandal, Tiger Watch

Dr. Khandal believes that all the species, as well as the landscape, in Ranthambhore need protecting, not just tigers; and he argues for the creation and maintenance of corridors, especially along rivers. Click the link to learn more about Tiger Watch and to donate to this worthwhile cause.

I asked Dr. Khandal about tiger tourism. “I’m pro tourism,” he said. “Tourism supports the local economy and it helped create a lobby for tigers. It’s only a menace if badly managed.” But he admit, there has been no study to date on the effect of tourism on tigers.

In Ranthambhore, there are for more beds for tourists in the many hotels and resorts in the area than there are seats available in the gypsies and canters that enter the park each day in search of tigers. (The number is restricted to manage the impact on the park’s eco systems.) Unfortunately, VIPs are allowed into the park above the maximum allowed.

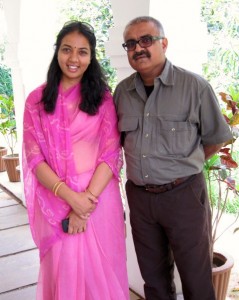

Usha and Goverdhan Rathore

After meeting Dr. Khandal, I had the pleasure of meeting Goverdhan Rathore, the son of Fateh Singh Rathore. I was delighted to meet him, and traveled with him to Khem Villas, the beautiful property he and his wife Usha own and manage.”It’s impossible to fill his shoes,” Goverdhan said about his legendary father. He spoke about his father with immense reverence, and sadness, in his voice.

Goverdhan and Usha were charming hosts, and showed me around the eco-friendly property and treated me to lunch in the open-air dining room. Khem Villas is a pitch-perfect “luxury jungle camp.” Spread over 20 acres, and located near the park, the camp features a choice of rooms, villas and luxury tent accommodation. Everything about Khem Villas is lovely, from the room decor, to the spa design; from the lotus pond to the private, outdoor soaking tubs. But the great selling point, aside from the charm of the owners, is the hotel’s location on the edge of the park. Water holes on the property attract many species, including the big cats, and walking trails allow for intimate interaction with the landscape (you are not allowed to walk inside Ranthambhore, except to the fort).

The spa at Khem Villas

After my lunch at Khem Villas, I ventured into the park for the first time, but just to go to the crumbling and evocative fort. Ranthambhore Fort is one of those many, many impossibly romantic places in India. Founded in the 10th century and seething with history, the fort is a photographic aphrodisiac, plus it affords panoramic views of the national park and houses several temples, including an important Ganesh temple.

Ranthambhore Fort

I finsihed my first full day in Ranthambhore with an obligatory stop at the Forest Office, where I was hoping to catch up with one Mr. Gupta and book my tiger safari in a gypsy (the smaller of two vehicles available). After a typically prolonged Indian scene, whereby several people looked at my credentials and I had to wait, inexplicably, I was told Mr Gupta was not available and I would have to call him that evening. Finally, with Satish Jain’s help, my booking was done and I was all set to go on my first tiger safari the next morning at 6 a.m.

The morning dawned clear and cool, and I woke up as excited as a child going to a birthday party! To defray costs, I shared my gypsy with a family of four from Chennai; and Satish came along with us. He is now the owner and manager of The Farm Villa, but previously he was a Ranthambhore guide for 15 years, so we were really lucky to have him along. Satish and I sat in the back of the open-air 4WD vehicle, and I got my Nikon D80 ready. At the park entrance, we were allotted our zone — one of five in the park — and off we went.

Moi with “weapon” in hand — Nikon D80

The park is open from 6 to 9:30 am, so we had only a couple of hours to track our “prey.” We drove throughout our zone, often coming across other gypsies or canters — the ungainly, 20-seat vehicles that reminded me of motorized hippoes. I can’t believe canters are good for the park. They were obviously created to maximize profit, not experience or forest preservation. We kept following clues, and tips from other guides, and came across many beautiful scenes of dry, deciduous forest, and the sight of spotted deer and sambar grazing, kingfisher birds darting and graceful white egrets soaring over a small lake, monkeys chattering in the trees and — the highlight for me — an enormous crocodile stretched out along the bank of a lake.

It was a wonderful morning, and though we didn’t see a tiger, I was not disappointed. I enjoyed the entire experience and felt captivated by the search for tiger. It has only bolstered my desire to visit some of India’s other tiger reserves — such as Kanha, Bandhavgarh and Corbett — and to continue to admire this magnificent creature and support efforts to protect it, and the landscape it inhabits.

Spot the croc

NOTE: The tiger in India incites both admiration and respect, and also fear, loathing and greed. On the one hand, it is idolized, and on the other, poached, hunted and not as well protected as its dire predicament would suggest is prudent. Below is some copy I lifted to give you a sense of the tiger’s position in India:

Shera was chosen as the official mascot of the 19th Commonwealth Games in Delhi. Shera is a Royal Bengal Tiger, and as the true representative of India, Shera embodies values that the nation is proud of: majesty, courage, power and grace. He is also a reminder of the fragile environment he lives in.

The Royal Bengal Tiger is the national animal of India. It is also an endangered species because of its vulnerability to habitat loss, poaching and environmental degradation.

Langurs, the black-faced monkeys, abound in Ranthambhore

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.