LADAKH IS THE NORTHERN most region of India, a high-altitude desert of stark beauty, arid landscapes, Tibetan influenced culture and mountain passes that can get snowed in almost all year round. Below, is the Tibetan Buddhist temple at Matho Monastery.

It’s a dream destination for photographers, Buddhists, trekkers, motorcyclists, people interested in Tibetan culture and those on the hippie trail. The landscapes are vast, the sky moody and the international borders loom. It’s place that gets seared into the souls of many who make the effort to visit. Below, the Matho Monastery is home of the Matho Museum project.

Here, I learned how a French Thangka restoration export, a Buddhist nun and the founder of a women’s fair trade store were reviving Ladakh’s Culture.

I went to Ladakh in September, just at the end of the tourist season, with my eyes open — to witness the beauty of the landscape and discover another face of India. I toured the monasteries and markets, visited chortens and chai shops.

Though I loved what I saw of Leh and Ladakh, it was the women who interested me. I’d heard Ladakh was a good place to be a woman in India; that women have more power and autonomy there than other places “down south.” While I was in Ladakh, I met and interviewed three women, one foreign, two local, who are contributing immensely to the local culture and the livelihood of women.

Preserving the Past

Nelly Rieuf at the Matho Monastery museum site

Nelly Rieuf, Matho Museum Project

My second day in Ladakh. With driver Tenzing and guide Tashi, we drove along a flat, dry desert, ringed with jagged mountains, past lonely chortens, grazing yaks and wild donkeys. I couldn’t breathe deeply because of the high altitude, but I inhaled the austere beauty. It looked like Tibet and felt like the roof of the world.

After about two hours we reached 500-year-old Matho Monastery outside of Leh. Matho Monastery, up a hill above Matho Village, is a small serene place whipped by winds and home to 30 monks. I toured the ornate temple and the museum that contained a snow leopard skin, the hat and mask of an Oracle and religious ornaments made from human bones and skulls, and exulted in the panoramic views of the Indus Valley and distant mountains.

Then, as I was leaving, I noticed some foreign women painting flower pots, and they told me they were volunteers, living at the monastery in a guest house, and part of a restoration and museum project. They pointed to a row of windows above the temple and said I should go up and take a look at the workshop that employed local women and foreign volunteers. So I did. And there I met Nelly Rieuf and her team.

Nelly is a young woman from France, and though only in her late 20s, she’s already a Thangka restoration expert and has lived and worked in India and Nepal for more than six years. She learned the art of Thangka restoration from her aunt when she was only 18, in Paris. Thangkas are paintings on cotton, or silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity or mandala.

For about four years, Nelly has been spending part of each year here at Matho Monastery, restoring Thangkas with the help of women from Matho village, whom she has trained; and acting as project manager for the Matho Museum initiative. I saw several of the local women, working meticulously on ancient, intricate images. When I asked why women, and not men, Nelly said the women are more reliable. She also employs foreigners, as researchers, and I saw three of them lined up against a wall, working on laptops.

A local woman restoration expert

Nelly was lured to Matho Monastery from Nepal, where she lives in Mustang with her Nepalese husband, by the promise of treasure. She was told the monastery had six, unopened boxes of art and artifacts. When she opened them, she found, among other things, one of the oldest Thangkas in Ladakh. “It’s Kashmiri style, totally unique, from about 1150,” Nelly told me.

But the Thangka restoration is only part of Nelly’s work at Matho. She is also helping to build a museum, to hold the six boxes of treasures. We walked through the construction site, at the back of the monastery, which Nelly said will be ready by June 2015. Even here some of the workers are local women.

I told Nelly how impressed I was by her work, and her team, and all they are doing to preserve the culture. She’s very passionate about the project, and also realistic about daily life.

“It’s not an easy place to live,” Nelly said. “We have no proper toilet, we have to bathe in the icy cold river and in winter there is very little food, just rice, potatoes and dal. But I am surrounded by the best of people. The women from the village are proud of their work here, they see themselves as protectors of their culture. They have hope and confidence, they are earning, they can now consider buying a sewing machine. It makes me feel emotional, to think I have made a difference.”

Nelly walks me part way down the barren hill to where my car is waiting. The wind whips our hair around our faces, and dries our eyes. Mine might otherwise be moist at meeting this energetic, frank and seemingly fearless young woman.

Nelly lives in harsh conditions, doing work she loves, and inspiring many people around her to trust in her and her team, to believe in the work and its value, and to join her in helping preserve and protect the unique and beautiful culture of Ladakh. She is giving local women undreamt-of opportunities to learn and earn and, perhaps most of all, leading a life of meaningful work and passion. Such people, such lives, inspire us all.

Giving Women Hope

Tsering Dolma at Ladakh Nature Products

Tsering Dolma, Ladakh Nature Products

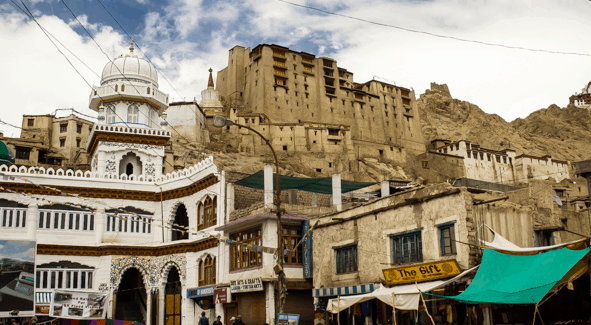

It took two or three visits to the main market in Leh before we found Ladakh Nature Products open. It’s not easy to find, especially as the main market was torn apart for roadwork. We walked gingerly on haphazard planks strew across crevasses in the road, past withered ladies in shawls, Israeli hippies in flowing harem pants and bands of Muslim youths raising money to help the Kashmiri flood victims.

The market is a long L-shaped street lined with cafes, street vendors and shops selling the usual assortment of scarves, bangles, bags and turquoise jewelry you find in all Indian tourist towns. Almost none of it is made in Ladakh. Above the street, the imposing 17th century Leh Palace, etched against the mottled sky, gives the scene its distinctive Himalayan atmosphere.

Finally at the end of the L, we find Ladakh Nature Products. It’s a very small shop, tucked under a sloping roof, and the shelves are jammed with wool products — from hats to shawls, from toys to slippers. All of the products are fair trade, made by rural women using local materials and traditional skills.

Sitting just inside, working with a felting awl on her lap, is Tsering Dolma, a slim, elegant woman who is the driving force behind the store and the Ladakhi Rural Women’s Enterprise.

Tsering founded the Ladakhi Rural Women’s Enterprise in 2012 to help empower Ladakhi women and preserve Ladakhi culture, largely through training women artisans. The store opened in June 2013 to retail the products the women make. Profits are put back into the organization to train and support women artisans across Ladakh.

Some of the fair trade fibre arts on sale at the store

I sat down carefully on a stack of felt to talk to Tsering Dolma about the social enterprise organization she runs, and how it came to be. Through my guide Tashi, who interpreted both my questions and her answers, I learned that she worked for 20 years with rural woman, in ecological development groups, with an organization called Ladakh Ecological Development Group (LEDeG).

Tsering has been training Ladakhi women in fibre arts since 2001 — teaching skills such as spinning, knitting, weaving, sewing, felting and natural dyeing. She told me that traditional culture is disappearing rapidly in Ladakh, and without this kind of organized effort it could be lost in a generation.

It seemed only natural to Tsering to start her own organization, and continue to build on the work she was doing with LEDeG. The Ladakhi Rural Women’s Enterprise currently keeps about 70 women, from all over Ladakh, busy making fibre arts to be sold at the Ladakh Nature Products store.

Tsering Dolma holding two pashmina shawls

While Tsering is telling me the story of her social enterprise, she also shows me some of the products. I ask to see pashmina shawls, of course, and she takes two from the shelf, both in natural colours of beige and off-white, very simple, with no embroidery. These are all she has left, and they are expensive — about $150 each.

If you don’t know, pashmina wool comes from the underside of a Himalayan mountain goat, and is closely related to cashmere, a wool that comes from Kashmir, a neighbouring region to Ladakh. Pashmina is said to be a finer wool than cashmere. Unfortunately, the word pashmina has come to be associated with a wide range of shawls — some that have no wool in the mix at all. If someone is trying to sell you a “real pashmina” for $10, it is not a real pashmina. It is just a shawl made from wool, silk, a synthetic fibre, or a blend.

I am very tempted to buy one of the shawls, as I know for sure they are real pashmina, and luxuriously soft to the touch. But I balk at the expenditure and instead buy a pashmina toque for about $20. I also pick up a bottle of apricot oil, for dry skin.

I have to agree with the Ladakh Nature Products website: “Leh is full of souvenir shops, but Ladakh Nature Products stands out as an authentic local gem!” And so does Tsering. It’s heartening to meet women like her, and see how they are bolstering the local economy, giving women opportunities and preserving traditional skills. If you go to Leh, be sure to save your souvenir money, and seek out Ladakh Nature Products.

Gender Equality in Religion

Dr. Tsering Palmo, right, with a top student

Dr. Tsering Palmo, Ladakh Nuns Association

Awhile ago, I read a blog post by Shivya Nath of The Shooting Star about her visit to a nunnery near Leh, called Living with the nuns of Ladakh. I loved this post, and wanted to meet the young nuns myself when in Ladakh. But I didn’t note the name of the nunnery, or place, thinking I would look it up on the internet once I was in Ladakh.

I was in for a shock. There was no internet access in Ladakh whatsoever due to the terrible floods ravaging Kashmir, and my prepaid phone was barred from cellular access due to security concerns. I was completely unplugged in Ladakh, living off the communications grid, open to only the people, places, ideas and experiences in front of me. It was exhilarating … but it meant I didn’t get to the Thiksey nunnery Shivya wrote about.

Instead, I went to meet and chat with Dr. Tsering Palmo of the Ladakh Nuns Association about the experience of being a Buddhist nun in Ladakh. She is a cheerful woman with a robust laugh and obvious strength of character. In a quiet, modest way, she instills in the visitor instant respect — much in the same way as the Dalai Lama.

Dr. Palmo founded the Ladakh Nuns Association (LNA) in 1996. It was given encouragement from His Holiness when he visited Ladakh in 1999, and “expressed his support for nuns, and stressed the need for the uplifting of nuns in Ladakh.”

Sitting in her LNA office, in a building that also houses a training centre, Dr. Palmo explained to me that nuns do not get the same opportunities and support that monks receive. The LNA is trying to rectify the imbalance, and both keep the tradition of nunneries alive and give the nuns more opportunities for education, especially in traditional Tibetan medicine.

“We’ve been a neglected group,” Dr. Palmo said. “There were no facilities for nuns, no training, no accommodation at temples (unlike for monks). And many nuns were also exploited. Some families just want one daughter to become a nun so they make her into a housemaid. We established this organization to change these traditions.”

Dr. Palmo said that women in her community traditionally become Tibetan medicine practitioners, and the LNA is encouraging this field of study. They offer training for women and health clinics to the community — and she is especially interested in mental and emotional health.

“We are lacking in people who listen from their hearts,” she said. “We want to offer a space for every woman to come and receive treatment for emotional and spiritual health. It is a Buddhist practise to listen. It’s important for us to develop compassion within ourselves, so we can listen to students, and try to transform negative thinking.”

I am very moved by her words, and ask her if the LNA offers any opportunities for foreign volunteers. “Yes, we welcome tourists to share their knowledge and experience,” she responds enthusiastically. “We are interested in having volunteers with medical skills, and softer skills too, to come and teach us. They can also stay in the two-room guesthouse if they want.”

If you want to learn more about the many activities of the vibrant Ladakh Nuns Association, and how you can help (you can donate, volunteer or contribute to a scholarship program), visit the website.

I left Dr. Palmo’s office, and Ladakh, uplifted as much by the soaring hearts and spirits of these three remarkable women as by the crisp mountain air and soaring Himalayan peaks.

Note: Thank you to India Tourism for giving me the hospitality to visit the Ladakh region.

Mariellen Ward is a freelance travel writer whose personal style is informed by a background in journalism, a dedication to yoga and a passion for sharing the beauty of India’s culture and wisdom with the world. She has traveled for about a year altogether in India and publishes an India travel blog, Breathedreamgo.com. Mariellen also writes for magazines and newspapers.