Welcome to the ever so quaint Cotswolds in England, a lovely drive west from London, which will not just take your breath away, but take you back in time. By the time you get there, you are ready for this transport! The trees, the shops, the inns — glorious.

Old Mill at Lower Slaughter is owned by Gerald Harris, a well known jazz singer from north London. His pretty (and) efficient daughter Linda runs the Mill store and manages visitors at the museum with him. He tells me that one fine day he and the family came to Bourton-on-water for a holiday, and fell so much in love with the solitude of this place, that he never went back! Not too many people follow their dreams with such a passion. And when they turn out chivalrous and charming, you wouldn’t mind the thin streak of narcissism that come as a package!

It’s not everyday that you get to be personally chauffeured in a zipping Porsche Cayenne Turbo, through roads which show you the horizon, clouds that take the shape of hearts and white wild-flowers spread on rolling hills nodding their head in agreement…to the quaint little station of Moreton-on-Marsh, to catch the last train to Paddington! Why? Because I got late hopping onto the tour bus with the others, while chatting with him across the counter ,swirling away a cone of elderflower flavoured ice-cream!

That’s how my trip to the Cotswold ends. I started telling you the tale, backwards……and, deliberately so. You need to take a step back and revisit time, if you are in the Cotswold. England’s Cotswolds villages — while just a couple of hours’ drive away from London — feel like a world apart. This tidy little region of characteristic old towns and gentle green hills is perfect for travelers looking to balance urban Britain with some thatched cuteness. Each of Europe’s famously quaint regions has a historical basis for its present-day charm. For the Cotswolds, it’s a combination of old sheep wealth, which produced big fancy manor houses, gorgeous churches, and stately market towns — all paid for by wool — and isolation from the rest of England, both economically and physically.

With the rise of cotton and the Industrial Revolution, the wool industry collapsed, people moved to the big cities. Time stood still in the Cotswolds towns for a while. Suddenly, attracted possibly by the beautiful landscape settings, the once wealthy merchants, families who inherited large sums of money soon started coming back to purchase or live in these honey kissed homes. It remained incognito for a while, away from main-line vision. That, combined with sparse highway and train service to the region, turned the Cotswolds into a kind of backwater that seemed to miss out on the modern economic current.

While I often get tempted to overuse the word ‘quaint’, I have to save the word for this emerald hamlet. By quaint, I don’t mean just thatched huts, stunning flowerbeds, brooks and charming teahouses. There’s a quirkiness — a jigsaw of time-passed, devitalized-nobility, clueless-aristocracy, rustic-naivety of the region — that charmed me to no end.

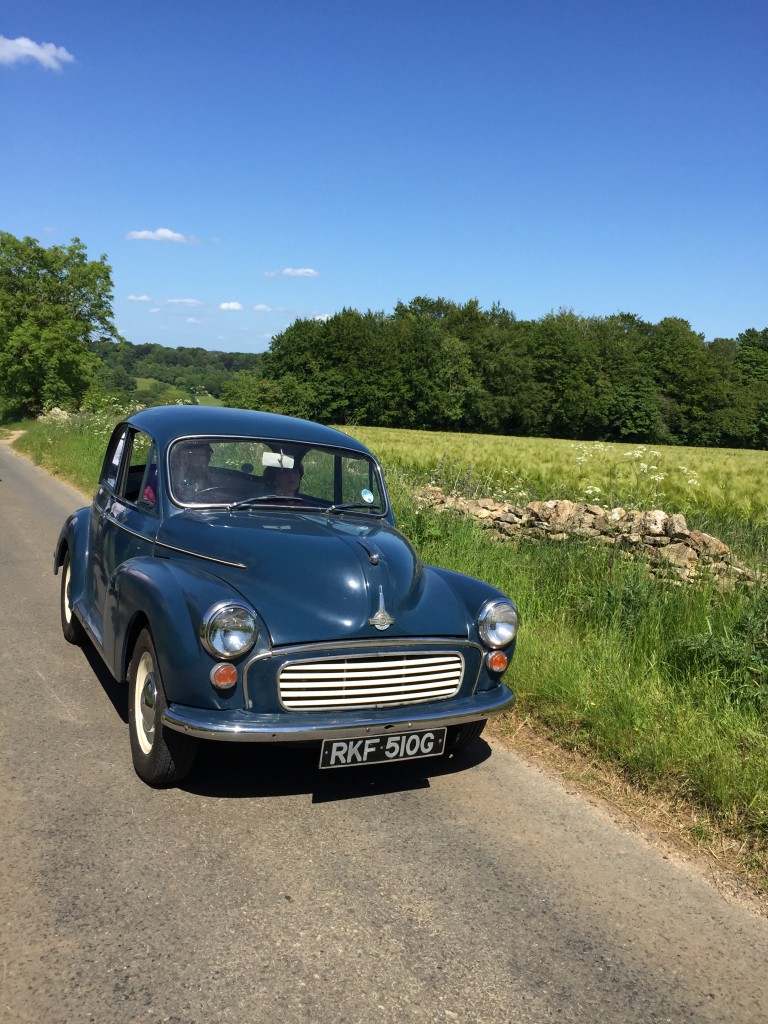

The Cotswolds are crisscrossed with hedgerows, dotted with storybook villages, sprinkled with sheep, occasional handsome horses, vintage cars that people still drive and vales that form chiffon contours.

Chipping Campden was apparently once the home of the richest Cotswold wool merchants. Like most market towns, there is a High Street. The street was once wide enough for sheep business on market days, when livestock and packhorses laden with piles of freshly shorn fleece would fill the streets! Today it has two cute tea rooms, pubs, a flower shop, a pet shop, pretty balconies with poppies and pansies and a parade of stone buildings.

Despite differing architectural styles, they are all made from the same Cotswold stone — the only stone allowed today. At the center of town is the 17th-century Market Hall, Chipping Campden’s most famous monument. Back then, it was an elegant — even over-the-top — shopping hall for the townsfolk who’d come here to buy their produce. Today, the hall, which is rarely used, stands as a testimony to the importance of trade to medieval Campden.

This is where I stopped for lunch. At Noel Arms Hotel – one of the oldest Cotswold inns and steeped in history. They say that Charles II stayed here during the English Civil War. Thankfully, things are a bit more relaxed these days! Head Chef, Indunil Upatissa has won the Great British Pub Awards for Best Curry Chef three years in a row and is the current title holder. I couldn’t simply leave this town without experiencing one of his famous beef curries, and a pint of beer now, can I?

After a finger-licking good meal, next was a stop at Britain’s finest ‘wool’ church (well, a church built with the money of the wool-trade!) to thank the lord for the good food! The St. James Church is quite an imposing composition on its own- with pinnacles topping the diagonal buttresses and a pierced parapet with ogee arches, soaring high above the terrain. Under the red carpet leading you towards the alter, lies a secret passage, tells us Sister Gertrude. That’s where was a secret passage leading families to a safer environment during the Civil war! Now, the rung on the big metal slab doesn’t open up.

The rushing River Eye powers a historic mill on the northwestern edge of Lower Slaughter. The Slaughters derive their names from the Anglo-Saxon words ‘slough’ meaning wet land and ‘slohtre’ a muddy place or from the name of their Norman landowners.

Nothing in all earnest, to do with any kind of slaughters! In quiet eddies at the back of the river, in gleeful laziness, wild ducks and handsome swans wade. Oh what a pretty sight to see a mother swan carrying a cygnet on her back. The little one falls, scrambles up, tags on to the wings, squeaks and is back again on mumma’s back! From the Upper Slaughter to the Lower, the path passes sheep grazing ‘Yash Chopra’ meadows, antique houses crafted from local honey-colored stone, stately trees arching over ancient millponds, kissing gates and footbridges that have endured centuries of foot traffic and rain.

The Mill Shop epitomizes quirkiness. Where else will you find hand creams, shaving soaps,jams & marmalade,30’s & 40’s jazz CDs,Mohair scarves, stone clocks, coal scuttles, honey and duck-feed all under one roof? The organic ice cream is served for take away only in sugar cones or tubs. Few for choice, but splendid. Vanilla,Butter Crunch,Ground Coffee,Wild Strawberry,Garden Mint Choc,Jamaican Rum & Raisin,Elderflower,Lemon Meringue,Brown Bread and Pistachio. And here is where my tongue (1. for mindlessly swirling the elderflower ice cream and 2. for indulging in the most interesting conversation with Gerry) was responsible for the missed train to Paddington!

If I had to go back to the Cotswolds, I would spend much more time there. Visit Stanway, as sweet as a marshmallow in hot chocolate, spiced with eccentric characters and odd bits of history. I would stroll along Burford, where flowers trumpet, door knockers shine, and chatty locals go “It’s all so very … ummm … yyya.”

Lie down on the tall grass on the meadows, feet crossed in the air, a book in my hand dreaming about chuckling streams, ancient churches, old mills and millponds, deep green valleys and villages out of a storybook, gnawed by time and echoing with centuries of youthful exuberance.

Sambrita Basu is a food-fascinated travel writer and photographer based out of Bangalore India. A background and a degree in hospitality and restaurant management paved her interest in food. As the secretary of the institution’s editorial club, she contributed regularly and wrote about food in their annual magazine, A la Carte.

Sambrita has published interviews of celebrity authors and business veterans in international publications like Infineon. Her contributions also include photographs on foods and restaurants of Bangalore for DNA—a leading newspaper publication in Bangalore. Sambrita’s creative expressions transport readers to alleys, hotels, hide-outs, restaurants, attics, and spice markets in several cities across the world.

Sam (as she is popularly known by her friends and family) doesn’t write for a living, but she lives to write.