“Moro, moro,” I say in OtjiHimba, smiling into the smooth ochre-covered face of the Himba woman as I shake her hand, gripping her fingers by curling mine in, and shake once more.

She’s beautiful, her dark brown skin glowing red from the grounded ochre stone made into powder, mixed with cow milk fat (the mixture is called otjize) and applied to the entire body for beauty, sun protection and skin health. She’s wearing her hair dreaded in thick clay ochre with it loose at the ends — symbolizing she’s gone through puberty, otherwise she would have two plaits of braided hair styled forward on top of the head, or one if she were a male. There’s a decorative erembe crown crafted from cow and goat leather on top meaning she’s married for at least a year or has a child, as well as decorative beads on her ankles lined with two leather stripes, signifying she has two children. She’s topless, her breasts hanging bare, though on her neck is a large shell necklace meant for beauty and on her waist is a calfskin skirt.

“Where are is your boyfriend?” she asks, with my guide George translating.

“At home,” I say.

“You must have been afraid I would steal him,” she says, a smirk in her eye. Beauty and a sense of humor.

Young boys have one braid toward the front (young girls have two)

I’m currently visiting a Himba village of Ohunguomure in the Opuwo. Children run around, some naked and some in long tees and tanks, rolling around on a broken Ford truck back and having a jumping competition. The few Himba men dressed surprisingly in Western clothing hang in a secluded spot of the village, which is surrounded by a wooden fence. Most of the men are out herding their livestock — which is the equivalent of money to Westerners — or possibly in another village courting another partner, as the Himbas are polygamous and men typically have two wives. Arranged marriages are also common among the Himbas, and a young girl of 13 may already have a husband chosen for her. Once married, the man will bring the woman back to his village to live.

Himba children having a jumping contest

Because of this female Himbas form strong bonds, as they’re left in the villages to take care of the children, cook the food, build the homes and sell the handicrafts.

History Of The Himbas

In the 16th century the Himbas migrated from the central eastern part of Africa as cattle herders. They followed the rivers from Angola to Namibia, and when the rivers became dry continued on, following the Kunene River toward the Atlantic Ocean. These waters were essential for drinking and allowing greens to grow for cattle to graze. Migration continued, with part of the group staying in Opuwo and the other continuing on and later becoming the Herero, the tribe my guide George descends from. We’d seen the Herero women in the Otjiikaneno Village wearing ornate German-influenced Victorian dress — wild to think about as they once dressed just like the Himbas, whose attire is now completely different.

The Himbas that remained behind didn’t have contact with the outside world for a long time — until Namibian Independence in 1990, when local tourism really started — which is how their culture is so strong. It’s so different from anything I’ve ever seen: the dress, the comfort with nudity, the small huts made from cow dung and straw, the beliefs, the sense of community, and sharing of goods and food. Sheesh, if someone asks for a bite of my candy bar I practically growl at them.

Himba women starting to lay out their handicrafts

In the center of the village is an enclosure made from mopane tree wood that keeps the livestock inside. In front, a Holy Fire billows smoke, always burning to assist in communicating with the ancestral spirits. The link must never be broken, and so it is forbidden for anyone to walk between the Holy Fire and the livestock enclosure. The main hut of the Chief is in front of the Fire, though the Chief of this village has passed away. A gravestone adorned with painted cattle with its own enclosure sits nearby, and his family lives in the main hut.

Assimilating With The Himbas

George helps myself and my three other group members to assimilate instead of being outsiders. We even go into the main hut to learn more, sitting on cow hide rugs covering the floor, which are the Himbas’ beds. We’re told 7-10 people could sleep in the tiny hut, which is something else very foreign to me.

My guide, George, with the Himba village (now deceased) Chief’s wife….

George also notes that unmarried women do sleep with their boyfriends, with the Himba man going to his Himba girlfriend’s village hut.

“So how does someone sleep with their significant other if they share a tent with nine other people? Do they inform them before?” I ask incredulously.

George explains. “No. You would sneak them in after everyone has gone to sleep.”

I’m still not understanding. “But wouldn’t the others wake up?”

“They would probably pretend to be asleep if they did. It’s really for the respect of the elders. The man would get to the woman’s hut late when is dark, leaving in the early morning while the elders are still sleeping. ”

As someone who lives in NYC I always complain I have no space and need more, but seeing this makes me realize the things we think we need sometimes seem this way only because it’s what we’re accustomed to.

A Visit Inside The Chief’s Hut

The Chief’s daughter sits pounding ochre stone into powder using a flat rock and a round rock, placing the finished product into a cattle horn to pass around. Soon we are coated in red just like the Himbas. The daughter then burns herbs and tree roots to blend into a fragrant smoke, which she wafts into her skin as a perfume as the Himbas don’t typically bathe due to lack of water resources.

The Chief’s daughter showing us how she applies ochre to her skin

My partial Himba transformation

Around us the walls are dangling with decorative garments, similar to a western closet. The daughter takes down a few marriage ceremonial headdresses, a lighter one with colorful beads signifying the woman has no children and a heavier darker one signifying the woman already had children. By the way, in the Himba culture if a husband dies and has a single brother, this brother can inherit the wife and children. Divorce is also a practice, though the woman must remember that whatever the man gave her family as a dowry — say, four cattle — they must give back double — eight cattle. Before this you may sit under a mopane tree and try to settle things with the help of the village elders.

It’s the traditional Himba form of modern western courts.

The Chief’s daughter modeling the different headdresses that give insight into a Himba woman’s life

The Chief’s daughter shows us how she makes her daily perfume

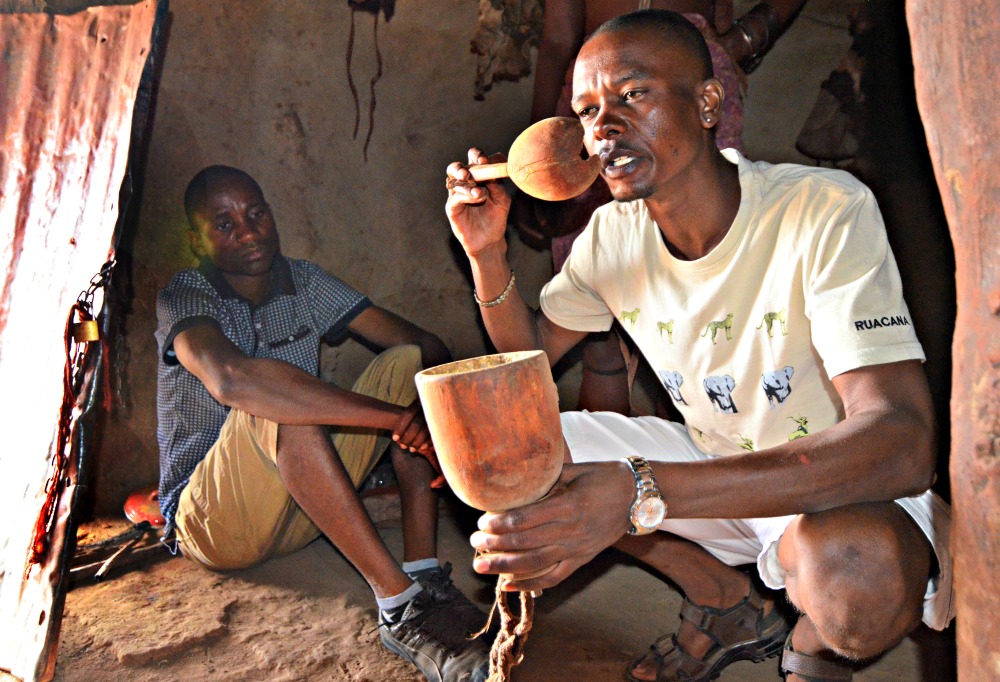

We also see what great recyclers the Himbas are, as reconstructed calabash are made into bowls, spoons and other household essentials. Their handicrafts also often incorporate repurposed items like piping and natural materials like wood, parasitic plants, seeds, leather and gemstones paying homage to Namibia’s mining heritage.

George demonstrating how the calabash has been repurposed for kitchen use

Transformative Travel

My favorite part of the experience is interacting with the Himbas. Many of the women are interested in my tattoos, rubbing their hands on my forearm where inky flowers bloom. I pull my t-shirt off my shoulder to expose the small birds, and suddenly a slew of young women and children are touching the skin.

The kids are amazing, so excited to play and to have their photos taken. With each picture, I show the children and their families to get the thumbs up of approval, which is a gesture I’ve found helps me to communicate without words. I use my fingers to also negotiate when purchasing handicrafts when the Himba women from this and the nearby villages form a circle with decorative sheets to display their wares.

While this village in particular has about six women, there are now over 20 including those from nearby. This part of the stay is a bit more aggressive than I’d like, as the women cry out to come to them and thrust bracelets and wooden dolls into our hands, though luckily George assists in keeping things calm. In fact, I leave with two beautiful hand-carved dolls for 150 Namibian dollars (~10).

The Himba woman I purchased the carvings from

George explains that it’s important to help support them but to not just give money when they insist, because it makes it worse for the next person who visits.

I take this to heart, as I think it’s very important when interacting with another culture to appreciate the differences, but to also immerse yourself in the experience as much as possible and resist treating the group like a human zoo. I imagine coming here without George, ignorant and having no idea how to act or what is appropriate. Maybe I would have walked between the Holy Fire and the livestock enclosure — a serious act of disrespect to the Himbas — or given them $20 to let me take some photos. Not only is that inauthentic, but these acts have negative consequences.

I also think it’s important to take something away from the experience. For me, I couldn’t get over the sense of community. Women helping other women raise their children, the sharing of resources they each work so hard to procure, the intense bonding and desire to help without such a focus on self. I’m also amazed at how closely they still live to nature, especially in this age when robots are threatening to take over any day now. While at home I try to live as naturally as possible, purchasing handmade vegan skincare and eating largely vegetarian, I’m nowhere close to the Himbas level of dedication. For them, though, this is their traditions and the life they know, not a transformation into some more noble way of living.

A Change In Himba Culture

While extremely well-preserved, things are changing for the Himbas. According to George, the reason we hear a radio playing music in the village or see Himbas with cell phones is because of Western influence and tourism.

“I’m not saying it’s bad. We all change. Kids are starting to go to school and get an education. And tourism supports them. It’s also important to interact with them and be one with them, and not just walk in and take photos and give them money.”

This helps form a cross-cultural connection and interact responsibly. Having a good guide is also essential to translate, to help you communicate and to tell you about what you are experiencing. Otherwise, you may just find yourself being asked for money with no real cultural or transformative experience.

Himba women and children in the village

We end up driving some of the Himbas about 20 minutes away into the main part of Opuwo, as these people do shop for their basic needs as well as grab a beer from time to time. This to me is an unusual site, topless Himbas with their elaborate headdresses walking alongside women in jeans and t-shirts, different cultures blending together in one place. The walk home for them is nothing, either, as they’re used to walking long distances.

My guide George was phenomenal. I met a number of other travelers who didn’t enjoy their Himba village experience because their guide didn’t translate or facilitate, meaning the guide can make or break the experience. You can contact George at gkatanga@gmail.com or through the Vulkan Ruine Tours & Transfers website.

I asked Vulkan Ruine Tours to provide some additional tips for visiting a Himba village responsibly to share with my readers. They advise:

- It is recommended to visit with a guide, who will be able to communicate to them in their own language and translate all they explain to you. The guide will also be able to inform you about their traditions and habits, what to do and what not. Please note that it is of great importance to abide by these rules or do’s and don’ts.

- If you would like to bring some presents to the Himba, it is advised that you bring items they can use, like porridge, flour, rice, cooking oil, tobacco and tea/coffee.

- It is not recommended to bring items from the western world, like little presents for the kids or sweets. The Himba tribe wants to maintain their own way of living.

- Common Himba courtesy means that it is always necessary to thank them formally for their time and hospitality when saying good-bye.

Logistics:

Stay: Opuwo Country Lodge. This was my favorite accommodation of the stay, as along with comfortable rooms the infinity pool and lounge chairs overlooking the city and mountains from a high perch is a destination in itself at sunset. There is free Wi-Fi in the lobby. Rates range from $10 per per per night for camping to $116 per night for a single person luxury room. The double standard room for $57 per per person night is a good value.

Local Guide: I used Vulkan Ruin Tours & Transfers and was extremely impressed with their dedication to responsible tourism and education. My guide, George, and driver, Martin, were both fun and knowledgable, helping to facilitate all activities in a way that helped our group get the most out of them. I would recommend requesting them when making your booking.

When To Go: Namibia is a year-round destination; however, for wildlife viewing June through October is best as it’s dry season.

Currency: The Namibian Dollar. As of March 3, 2016, the exchange rate is about $1 USD = $15.67 Namibian Dollars.

Language: English is the national language, though most also speak Afrikaans and German (Namibia experienced a period of German rule from 1884 under German South-West Africa).

Staying Connected: If you travel a lot a KnowRoaming Global SIM Sticker affixes to your SIM to give you local rates and eliminate roaming charges in 200+ countries. Otherwise, you can purchase a local SIM card from MTC. My starter pack cost about $5 and lasted me for eight days of pretty consistent use. Note: You’ll need an unlocked phone to be able to do this. You can call you cell phone provider to have this done if it’s not already.

Dress: Dress is casual and comfortable. While I’d read many guides saying you must cover your shoulders and knees, I didn’t find this to be the case in reality. While I’d skip dressing provocatively, shorts, tanks, tees and sundresses are totally fine.

Outlets: The four of us on my tour group ALL mistakenly brought the wrong converters. I even brought a 150+ country converter and it still didn’t work.

Must-Pack Essentials: Along with your typical gear, make sure to have:

- Sunscreen

- Light long sleeve shirt to block sun (I love the insect-repelling NosiLife line from Craghoppers)

- Sunglasses

- A hat (I like this insect repelling one from Craghoppers)

- Scarf-shawl (great for chilly nights and plane/car blankets)

- Aloe

- A Telephoto lens

- Namibian/South African Converter

- Personal alarm siren (I didn’t feel Namibia was dangerous, but I always carry this)

- Pickpocket-Proof Garments (again, something I always pack)

- BUFF (for sun and dust protection)

Jessica Festa is the editor of the travel sites Jessie on a Journey (http://jessieonajourney.com) and Epicure & Culture (http://epicureandculture.com). Along with blogging at We Blog The World, her byline has appeared in publications like Huffington Post, Gadling, Fodor’s, Travel + Escape, Matador, Viator, The Culture-Ist and many others. After getting her BA/MA in Communication from the State University of New York at Albany, she realized she wasn’t really to stop backpacking and made travel her full time job. Some of her most memorable experiences include studying abroad in Sydney, teaching English in Thailand, doing orphanage work in Ghana, hiking her way through South America and traveling solo through Europe. She has a passion for backpacking, adventure, hiking, wine and getting off the beaten path.