“The seat belt broke,” Nikola said, without elaborating further. Although we were surrounded by chatty couples, with not a single bench in Tašmajdan Park left unoccupied, the air was as silent as the sky was dark.

By “we,” I don’t mean “me, myself and I,”—I wasn’t sitting alone in a Belgrade park in the middle of the night, having an imaginary conversation with a Nikola Tesla statue. Nikola wasn’t an apartment owner or taxi driver or tourism office employee I’d befriended while going about my business, either.

He was an actual Serbian—an actual person!—I’d met under the pretense of hooking up, and he was in the middle of explaining why he’d been in a wheelchair the past two years when you interrupted us.

“How are you feeling, by the way?” He asked, and stole a french fry from me.

“I haven’t really been thinking about it—about him,” I sighed and took a bite of Pljeskavica, a Serbian hamburger thing usually enjoyed by people drunker than I was. “I’m sorry, again, about tonight.”

“You don’t need explain,” he put his hand on my shoulder. “Do you want to take a walk?”

“I do,” I said. “I wish I could stay seated like you, though.”

“Making jokes about me already, huh?” he laughed, rolling himself over to my side. “I like it.”

We began moving toward the edifice in the distance, the crosses atop it gleaming under the half-moon. It wasn’t until we got closer that I noticed how intricately designed the huge church was, in spite of how underwhelming its rustic façade had seemed from far away.

“I missed this one when I was exploring,” I noted, the extra-creepy eyes of Orthodox Jesus looking down at me in judgment. “I just saw shitty, half-done St. Sava.”

“Hey!” He exclaimed. “St. Sava’s not shitty—but it is half-done, you’re right. A national embarrassment.

“This one, however,” Nikola, who works as an architect, continued. “This is the Church of St. Mark. What’s unique about the style is the red color of the stuff between the bricks. What do you call that in English again?”

“Mortar.”

“Yes,” he raised his finger, “the red mortar.”

Just then, REO Speedwagon’s “Keep On Loving You” started blaring from one of the bars we passed. I’d last heard the song the day after I broke up with Danilo and now, as then, I wondered exactly what it meant in the context of my life.

“It’s not so much that he deleted me from Facebook that bothers me,” I changed the subject, seeking distraction from the memories of Penny the picture of Nikola with his elderly dog had stirred up in my head. “It’s that I guess, before it happened, I was conducting myself as if it somehow wasn’t over.”

We turned the corner onto picturesque Terazije Boulevard, the aforementioned Temple of St. Sava at one end and Republic Square at the other. For a split-second, however, the only images I could see were of me and Danilo, a light-speed slideshow of our year together that flickered past like a meteor shower.

“Earth to Robert,” Nikola snapped his finger in front of my face. “Continue what you were saying.”

I nodded in agreement. “I was consciously avoiding meeting people, for sex or for anything, really. Walking on eggshells, writing about him—and about us—cryptically, as if somehow he would see it and, if I’d been too candid, threaten to break up with me like he always did. Waiting for him to fire the next shot, even though I long ago held up—and put down—my white flag.

“I just need to stop talking about it,” I conceded, getting out of my head and back into the moment. Flashes of Danilo’s smile gave way to the sparkling of street lamps on the water below Kalemegdan Fortress, the confluence of the Sava River with the Danube. “I’m sorry to keep dwelling on this.”

“Yeah, it’s bad enough it made you not want to have sex with me,” he smiled. “See? Two can play the insensitive joke game.

“But really,” he went on. “I get it. It sucks.”

“Wait a minute,” I stopped, noticing the steep staircase in front of us. “How are we going to get up there?”

“We aren’t,” he turned his wheelchair sideways. “Or at least I’m not. There’s a ramp, but it’s too steep to go up. Accessibility is not really a priority here in Serbia—I took that for granted before my accident.”

“You really think I would go up without you?” I put my hand on his face.

“I sure as hell hope not,” he squeezed my wrist almost violently, to emphasize how strong his upper body still was. “For your sake.”

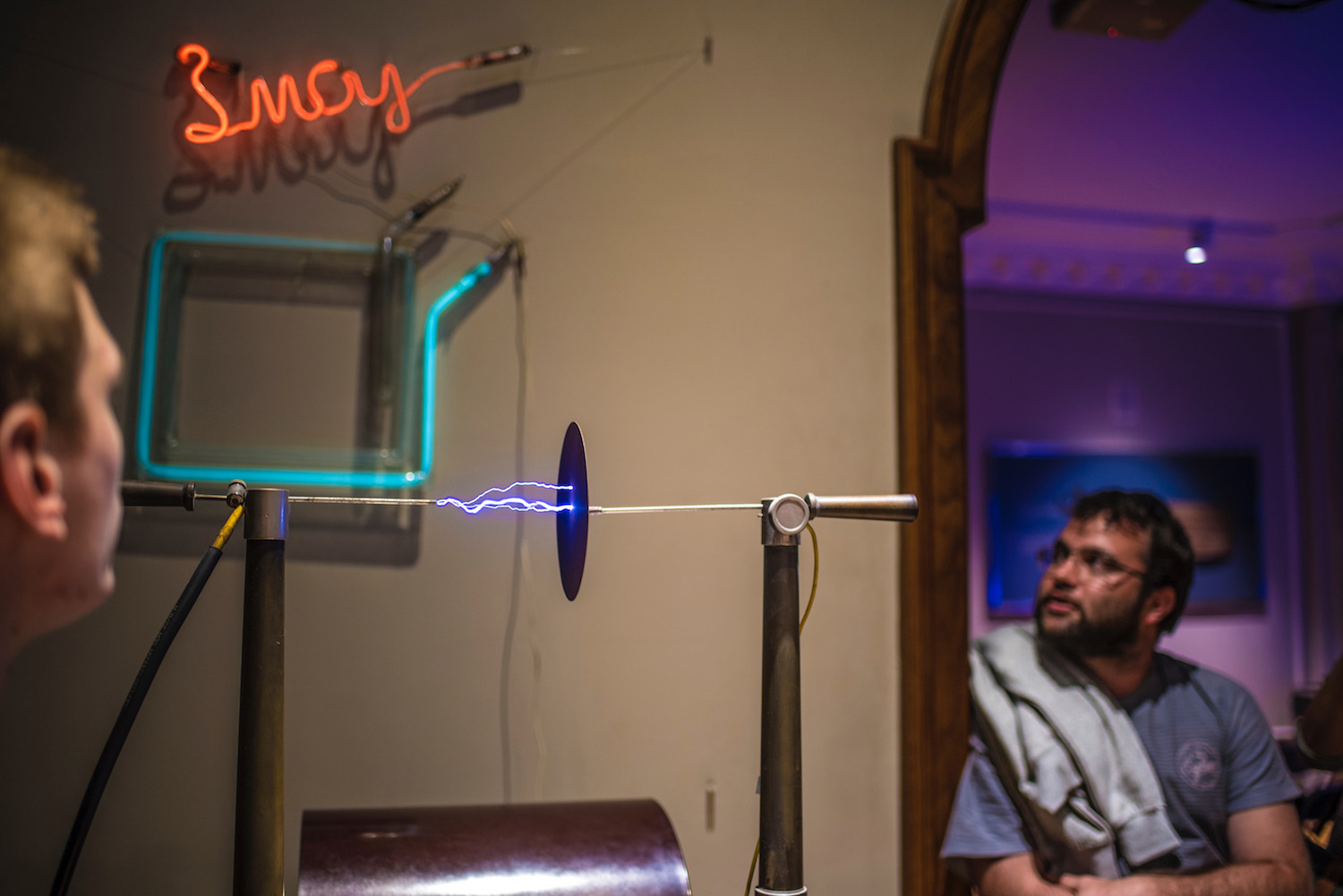

“I just don’t get it,” he scoffed as we passed the Nikola Tesla Museum, whose primitiveness is just as much of an insult to the man as the dilapidated airport named after him. “To me, we—Serbians, Bosnians, Croats, the lot us—we’re all the same.”

“That’s a good attitude to have,” I praised him. Much better than the one she had.

(“She” was a sweet, old winery worker I’d met in the town of Sremski Karlovci the day before. We’d been sipping Bermet, a Serbian desert wine notable for having been a guilty pleasure of Austrian empress Maria Theresa, when she suddenly launched into a tirade about how the “diversity” of cities like Belgrade would would be the downfall of society.)

“Well it’s not my attitude,” he corrected me, as we began circling the Trg Slvija roundabout for the third time. “It’s the truth, as I see it—we are genetically identical. I realize the war ended when I was in diapers, but I just don’t get it why people who lived together peacefully for so long started killing one another.”

I exhaled, looking up at the cacophonous, yet harmonious mish-mash of buildings rising in front of us.

“I don’t think it’s so much that people want war,” I said. “They’re afraid of peace, that life without a struggle will cease to be meaningful. I feel that way a lot.”

He looked up at me puzzledly. “Care to elaborate?”

“No,” I bent down, noticing the day’s first rays of light beaming over the horizon, and kissed him passionately. “I don’t.”

Robert Schrader is a travel writer and photographer who’s been roaming the world independently since 2005, writing for publications such as “CNNGo” and “Shanghaiist” along the way. His blog, Leave Your Daily Hell, provides a mix of travel advice, destination guides and personal essays covering the more esoteric aspects of life as a traveler.