Truth be told, I was surprised by Chongqing’s beauty. And I don’t mean the Muzak cover all All4One’s “I Swear” that was playing as I waited to clear Chinese immigration, although that was a nice touch.

This first jumped out to me in the taxi on the way to my hotel (if you can use that word to describe the place I stayed—more in a second), when I noticed bougainvillea vines exploding over the noise barriers lining the highway on either side. Bright bursts of fuchsia and watermelon and chartreuse, like botanical lights celebrating a never-ending Christmas.

The majority of Chongqing’s beauty, of course, is of a decidedly urban sort—it’s the most populous city-proper on the planet, by some measures. Also sometimes referred to as the “World’s Largest Village” it’s simultaneously infamous for the provincial mindset of its residents.

I’ll explore these accolades, the contradictions between them and much more as I explain the best way to spend three days in Chongqing, China.

Where to Stay in Chongqing

I used quotation marks above because Chongqing Deer Designer Hotel is simply the eighth floor of a soulless, grey residential building, whose great view belies its depressing location. I won’t bore you with further details (besides mentioning the blood on my “clean” sheets, and the staff’s apathy to it), but I will give you a piece of advice I wish I’d taken: Pay an extra $30 per night at stay at the Sofitel. Or the Sheraton. Or anywhere else, really.

Day One: The World’s Largest City

I used to hate taxis, I thought as the one I sat inside sat in traffic, the driver honking and shouting his way across the crowded bridge over the Jialing River. A random person from the street hadn’t climbed into my car as one did at the airport (I didn’t mention that a few paragraphs up, on account of the bougainvilleas and bloody hotel sheets), but I did see the metro station out my window and wonder whether I might be better served behaving like the Robert of yesteryear.

It didn’t matter, of course. Before I knew it I’d arrived at the Great Hall of the People, one of the only city-center structures in Chongqing that can pass as being traditional in any way—I’ll get to the rest in a minute.

A bit of advice: Save the ¥10 they charge for going inside—it’s just a modern-ish performance venue—to maintain the illusion that it actually is traditional. Instead, buy a jin of oranges from one of the migrant sellers outside the attraction just across People’s Square— Three Gorges Museum.

I’ve never had any desire to see the Three Gorges Dam, to be sure, but I did find the museum interesting, if only for the shameless propaganda. We appreciate the people who sacrificed individual benefit for national interest, the inscription said in capital letters, as if transcribed directly from Orwellian.

The rest of the afternoon, as I experienced it anyway, was pleasant but anti-climactic. My hot pot lunch at Chongqing Cygnet was delicious and entrail-free; walking through Chongqing’s aptly-named Times Square not only provided great photography opportunities, but allowed me to discover the only place in the world where Azealia Banks, who was shimmying across an LCD screen atop a forgettable shopping mall, is still relevant.

This is definitely not the viewpoint those pictures I saw were taken from, I sighed, looking across the Yangtze River at Chongqing’s massive skyline from the southern terminus of the Yangtze River Cableway, vowing to find the proper one on my second of three days in Chongqing.

Day Two: The World’s Largest Village

Ciqikou will be picturesque and charming by the time most of you read this, but when I visited it was still a hot mess. In addition to the fact that only someone as skilled as me could photograph it without being overwhelmed by the construction cranes that rise around it on all sides, I sat down to order an americano (at 10 a.m. no less—coffee shops here don’t open until 10, apparently as a matter of law) and received a half-assed version (with drip coffee instead of espresso) of an affogato instead. Ai yo!

My second of three days in Chongqing, to be sure, was defined by Chongqing’s less-flattering nickname.

There are two sides to this, of course. You see, while I couldn’t manage to find a taxi driver to take me to Nanshan (the correct viewpoint for the view I cited in the last section) without a large bribe, the flipside of Chongqing’s (and, to a lesser extent, China’s) lawlessness is that it extends outward in all directions: No one was atop the mountain to prevent me from walking up to the empty, open (and heavily restricted) eighth floor of the observatory from the crowded, glass-enclosed sixth.

No, I’m speaking more figuratively, in impressions rather than concrete facts, like the aroma of burning plastic that somehow made me nostalgic for my old life in Shanghai as I photographed Hongyadong from across the river. Or how the juxtaposition of Chongqing’s grand scale and lilliputian sense of identity evoked a sense of the past returning sometime in the future, the idea that the Cultural Revolution had removed color, but not shape or texture from China.

Day Three: Heaven, Hell and Chinese Bullet Trains

Physically speaking, Chinese bullet trains are identical (or at least, almost identical) to the Japanese Shinkansen. But Chinese passengers, bless their hearts, have managed to completely trash them in a fraction of the time. Which doesn’t matter, I suppose, given how fast one arrives at one’s destination, but it’s interesting to think about.

And where was I headed on my third of three days in Chongqing? Not very far away from the city’s incredible skyline, the view of which from Nanshan I still can’t stop thinking about, neither the pictures I took of it nor the extent to which they evoke Blade Runner, not in distance anyway.

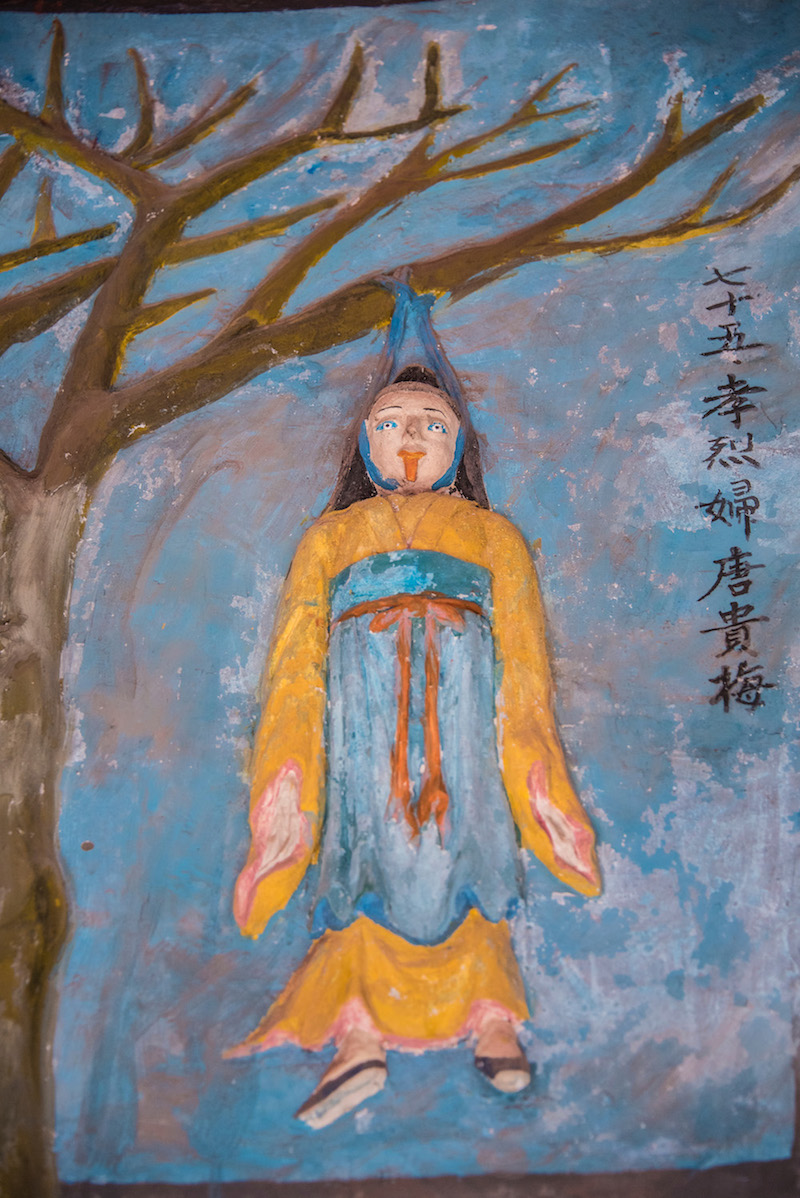

But Fengdu couldn’t be farther from Chongqing esoterically, if only because of the fact that its pagodas, shrines and visions of hell seem to be somewhat original. (Fengdu Ghost City, this is, not modern Fengdu, an industrial agglomeration along the Yangtze that’s bigger than many mid-sized American cities.)

Yes, I said “visions of hell”—Fengdu Ghost City presents various interpretations of an afterlife (heaven is there too), which is interesting especially if the work is original: Chinese atheism is stifling, and I say this an atheist. I can’t imagine something so blatantly spiritual making it through the Cultural Revolution.

I remember saying the phrase “Now, I’m really in China” twice on my third of three days in Chongqing, which I also considered spending at Dazu Caves, the other most-popular day trip from the city. The first time was during the three or so hours I spent walking up Ming Mountain and exploring the Ghost City, realizing that even if the structures weren’t quite original, they at least evoked what I imagined China would be like before I visited (and lived) here.

The second occurred when I boarded my return bus—all Chongqing-bound trains were sold out. As had happened years ago in Chengdu, when I made the mistake of trying to hike up a mountain whose trails had been destroyed in a recent earthquake, the driver compensated for the lack of empty seats by placing a plastic stool in the middle of the aisle for me to sit on.

The Bottom Line

I ended my three days in Chongqing in much the same way I began them: Inside a taxi, marveling at the seeming contradictions around me and wondering whether the whole was even in the same universe as the sum of the parts. I didn’t have a free rider in the car, and my driver didn’t refuse to take me to my destination, but he did decide to stop for gas (and attempt to charge me for the time we waited).

And he did make me laugh right before I otherwise would’ve boiled over with anger. “But they’re delicious,” he said in Chinese, after I declined his cigarette for the third time, saying it with such joy I imagined him eating it like a piece of licorice.

By the time we arrived at the train station, I was so distracted and confused—and, yes, emotional—that I hadn’t enough noticed if there was bougainvilleas this time, or what color they were. I did remember, however, that no quantity of Chinese vocabulary (Spoiler alert: If you don’t speak Chinese, your three days are Chongqing is going to seem very long) was a substitute for the right combination of hand gestures and yelling, which is why I believe the driver was so receptive to the 10 yuan I shorted him upon exiting the cab.

Robert Schrader is a travel writer and photographer who’s been roaming the world independently since 2005, writing for publications such as “CNNGo” and “Shanghaiist” along the way. His blog, Leave Your Daily Hell, provides a mix of travel advice, destination guides and personal essays covering the more esoteric aspects of life as a traveler.