When forests are cleared in West Africa for firewood or for farmland, the Dika trees are, more often than not, left untouched. Farmers have too much to gain from harvesting the tree’s fruits and seeds to burn or discard a Dika found in the wild.

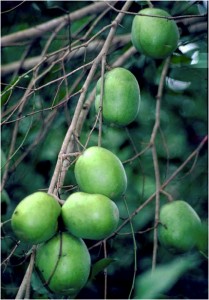

Indigenous to West Africa, a Dika tree can grow to be as tall as 40 meters and produces a small green and yellow fruit that looks, at first glance, like a small mango. (Photo credit: Lost Crops of Africa)

Indigenous to West Africa, a Dika tree can grow to be as tall as 40 meters and produces a small green and yellow fruit that looks, at first glance, like a small mango.

Its fruit ranges in taste from sweet to bitter and can be enjoyed—especially the sweeter varieties—fresh off the tree, or made into jelly, jam or “African-mango juice.”

But while the fruit is a delicious treat, the seeds are where the real value can be found. Resembling smooth walnuts, Dika seeds are cracked open by harvesters to collect the edible kernel contained inside.

These kernals can be eaten raw or roasted, but most are processed and pounded into Dika butter or compacted into bars or pressed to produce a cooking oil.

The seeds also produce a unique flavor when crushed and are combined with the other spices to make “ogbono soup,” a common dish. The wide popularity of ogbono soup has created a large market for Dika seeds and harvesters can trade Dika kernals at both the local and regional scale.

Out of season, Dika seeds bring in an especially high price—it has been estimated that a farmer can make up to $USD300.00 off of the seeds produced by just one tree.

Each year, thousands of tons of “Dika nuts” are harvested throughout Western Africa and the popularity of this wild tree has lead to many attempts at commercial cultivation.

The Dika is a slow maturing plant—it takes 10 to 15 years for a tree to begin bearing fruit. Breeders, motivated by the value of its fruit, are working on developing faster growing varieties as well as varieties with shells that are easier to crack open.

But whether or not the Dika is successfully tamed by breeders and made more commercially viable as a domestic crop, the tree in the wild is already providing a critical income to millions of farmers and harvesters throughout West Africa.

Molly Theobald is a Research Fellow with the Worldwatch Institute working with the Food & Agriculture team on State of the World 2011: Nourishing the Planet. Molly brings her skills as former Labor 2008 Pennsylvania State Communications Director for the National AFL-CIO, and her experience working on women’s issues, to her research and writing for Worldwatch where she focuses on sustainable agriculture as a means to alleviate hunger and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. She has a BA from Sarah Lawrence College where she concentrated in Women’s Studies and Social Justice.