When most people walk inside the Fire Temple of Yazd, they see Jesus in images of Zoraster, the familiar-looking mascot of the Zoroastrian religion. I did too, nodding my head as I watched old white women cross themselves, seemingly out of habit, to pay respect to a prophet with long hair, beard and skin whiter than a birthplace in southwestern Asia should’ve allowed.

As I began reading his story, however, and realized he was also known by the name “Zarathustra,” my mind went to the desert—thought not, notably, the Mesr Desert of Iran, where I’d spent a weekend before coming to Yazd.

Rather it was a lonely desert (the loneliest one, in fact) Friedrich Nietzsche described in his seminal Thus Spake Zarathustra, the place where the first of three spiritual metamorphoses required to reach one’s most liberated state occurs.

Liberation, of course, is a fraught topic in Iran, as I described in the first piece I wrote upon returning from the country. What I’ve written below is much more straightforward: A guide on how to make the most of your time in Yazd, the proverbial See of Zoroastrianism, and the beautiful (though not particularly lonely) desert that extends to the north and east of it.

Where to Stay in Yazd and the Mesr Desert

More than a week before I arrived in Yazd, the owner of my tour company personally warned me about the quality of hotels there. “There are only a couple of four-star hotels there,” he said, reminding me that Iran’s standards for awarding four stars are much lower than the rest of the world’s.

I won’t name the hotel I stayed at in Yazd—Fazeli Hotel, which is highly recommended, wasn’t it—but will mention that Barandaz Lodge, where I stayed in the Mesr Desert, was a highlight of my entire trip.

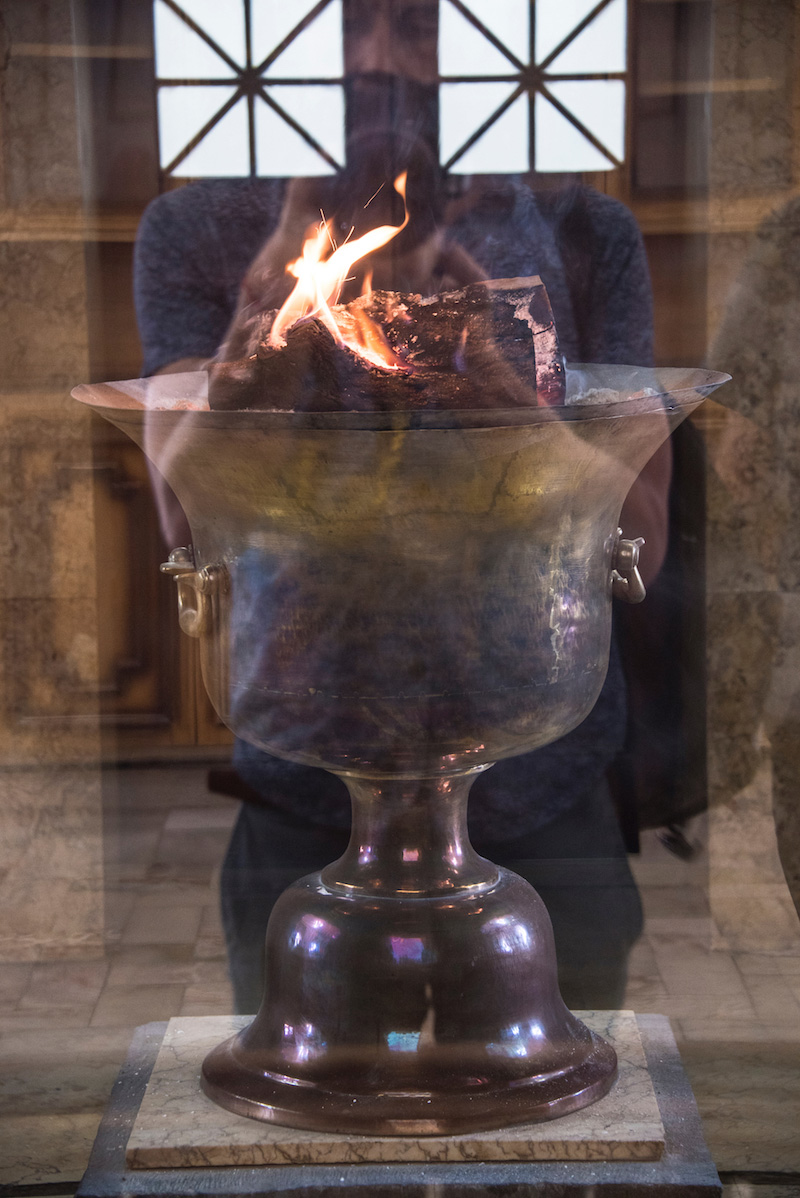

The Fire Temple and the Towers of Silence

The intro to this piece notwithstanding, the influence of Zoroastrianism in Yazd is understated, a fact I’d list as the most surprising part of the two days I spent there. Vestiges of the religion such as the Towers of Silence (where Zoroastrians once “buried” their dead so that their flesh would be picked clean by hawks; and which actually sits a bit outside the city center) and the aforementioned Fire Temple are conspicuous, but not numerous.

Yazd Beyond Zoroastrianism

To be sure, most of what Yazd has to offer travelers is related to Iran’s current main religion—Shia Islam—and not its original one. The 12th-century Jameh Mosque, for example, was actually built on the site of a fire temple demolished to make room for it—a world built on top of the Overmen, as it were.

Amir Chakhmaq Square and its mosque took shape more than 200 years later, but are aesthetically consistent with much of the rest of the Yazd Old Town.

Other important attractions in Yazd include a Prison that may or may not have been built by Alexander the Great, Yazd Water Museum and Dowlat Abad Garden, whose wind tower is but one of many working examples of air conditioning in Yazd, but the easiest both to visit and to experience—in addition to feel cool as you stand under it, you can hold out a piece of tissue and watch it float in the air!

The Mesr Desert: Egypt in Iran

My three days in Iran’s desert technically took place before I arrived in Yazd, but I’m placing them at the end of this makeshift itinerary for the sake of formatting.

Specifically, I ventured into the Mesr Desert (named as such because locals thought it resembled Egypt—Mesr in Farsi). Even more specifically than that I spent one night in Farazadh, which sits just on the edge of the dune-y part of the desert, before moving onto Garmeh, a beautiful oasis where date palms are grown.

On the way to Yazd I stopped in the village of Kharanakh, home to an awful caravanserai and an amazing (if poorly maintained) castle, followed by Merbod, whose much better caravanserai still left a lot to be desired, even if its ancient ice house was pretty cool. It wasn’t until I had entered Yazd’s city limits that I realized how few wild camels I’d seen during my entire time in the desert.

This is the loneliest desert, at least from the perspective of a camel, I silently admitted to myself, surmising that all the ones who used to live here had become lions, then children, then Overmen.

The Bottom Line

Iran’s desert, on its face, is far from the most amazing one I’ve seen in the world, and might actually be among the least inspiring. However, adding it to the city of Yazd (not to mention placing it in the monumental and oft-overlooked context of Zoroastrianism) makes this part of Iran a must-visit, and a highlight of any trip to the Islamic Republic.

I traveled in Yazd (and the rest of Iran) courtesy of Surfiran. Whether you’re looking for a comprehensive Iran tour (which you’ll legally need if you’re American, Canadian or British) or simply need piecemeal Iran travel services, Surfiran can help you take your trip to the next level.

Robert Schrader is a travel writer and photographer who’s been roaming the world independently since 2005, writing for publications such as “CNNGo” and “Shanghaiist” along the way. His blog, Leave Your Daily Hell, provides a mix of travel advice, destination guides and personal essays covering the more esoteric aspects of life as a traveler.